The Big Read: Capital punishment — a little more conversation on a matter of life and death

SINGAPORE — When activist Kirsten Han told a member of the public a year or two ago that it may not always be cheaper to execute a death row inmate than imprison him for life, the response was: “But why? A bullet is so cheap.”

SINGAPORE — When activist Kirsten Han told a member of the public a year or two ago that it may not always be cheaper to execute a death row inmate than imprison him for life, the response was: “But why? A bullet is so cheap.”

“Setting aside the fact that we don’t execute by firing squad in Singapore, I was really quite taken aback by how glibly and casually that comment was made,” the freelance journalist told TODAY, adding that most Singaporeans she had met did not know much about how the death penalty works here.

Ms Han is one of only a handful of people from We Believe in Second Chances, and the Singapore Anti-Death Penalty Campaign, who are directly involved in anti-death penalty activism here. They work on cases and speak to death row inmates’ families.

In some ways, the small number of activists reflects how little the public is seized with the issue.

Nevertheless, rights groups such as Maruah, Think Centre and Function 8 also regularly speak out on the death penalty.

Maruah president Braema Mathi believes that Singaporeans have been “conditioned” to believe that the only way to deal with drug traffickers is to execute them.

“One individual who did attend a death penalty discussion told me: ‘They deserve it’, because drug addiction causes much harm to the family and they (drug traffickers) know, knowing it is a market to make money. Many among us easily transfer the causes to a single factor — the trafficker — and we have been conditioned, too, to see punishment as a single solution,” Ms Mathi added.

For anti-death penalty advocates like Ms Han and Ms Mathi, getting people involved in conversations about capital punishment here can be difficult. This, despite the fact that it is an issue which has been fervently discussed for many years not only in civil society and the legal fraternity here and abroad, but also in the hallowed chambers of the United Nations (UN).

In 2012, the Singapore Parliament passed laws to remove the mandatory death penalty in certain cases of drug trafficking, as well as in murder cases where there were no intention to kill.

The Ministry of Home Affairs is in the midst of conducting a national survey to understand public attitudes on the death penalty in Singapore, as part of the Government’s regular research on the country’s criminal justice system. The survey, which started in October and ends in December, involves 2,000 randomly selected Singaporeans and permanent residents.

In response to TODAY’s queries, Senior Parliamentary Secretary for Home Affairs Amrin Amin made clear that there “are currently no plans to review the use of the death penalty in Singapore”. Nevertheless, the survey aims to provide the Government with an updated understanding of public sentiment towards capital punishment, he added.

The Singapore Government has been firm in its stance on the death penalty for drug offences.

Last year, Law and Home Affairs Minister K Shanmugam spoke out against the “romantic” notions portrayed by those who oppose it.

Urging anti-death penalty activists to look at the big picture, instead of focusing on the individual getting hanged, Mr Shanmugam said: “What they do not focus on are the thousands of people whose lives are ruined, whose families are ruined, and the undoubted number of deaths that will occur if you take a more liberal approach towards drugs.”

Mr Shanmugam was speaking at a forum on combating drugs, which involved local and foreign delegates from government agencies, non-government organisations and civil society groups.

He added: “The rise in homicides, rise in crimes that lead to deaths, these are not theoretical arguments, you just look at the places where the drug situation has heightened, gotten out of control, or is under less control.”

Past surveys conducted in Singapore have shown that the public is highly supportive of the death penalty in general. However, some activists and lawyers believe this could be down to a lack of a deeper understanding about the matter.

And regardless which side one chooses to take, it should be done with proper knowledge and awareness of the issues involved, they added. In the same vein, the authorities should make available more information about death row cases and conduct more public studies, they suggested.

GLOBAL DEVELOPMENTS

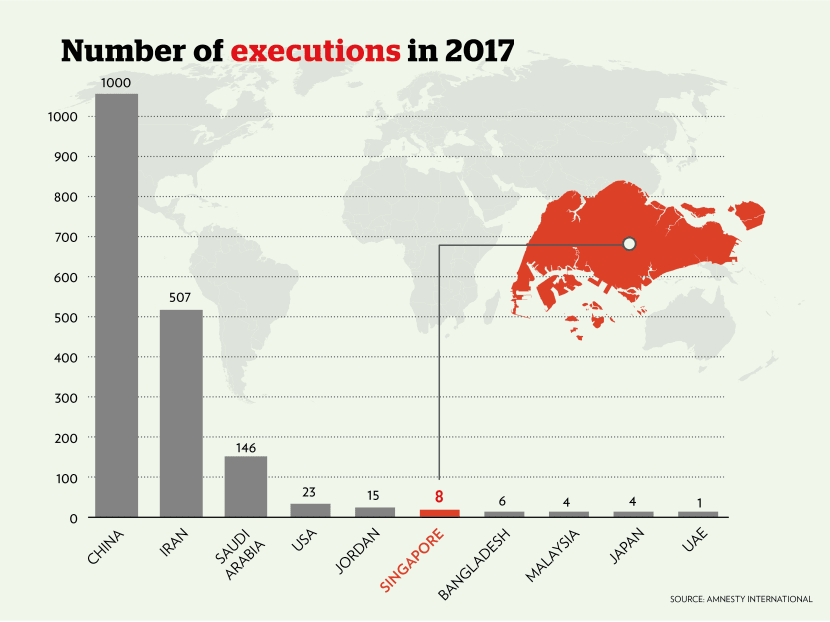

Singapore is among a shrinking list of jurisdictions where the death penalty remains in place. About two-thirds of executions in the Republic from 2007 to last year — 24 out of 36 — were for drug trafficking. The remaining, save for one related to the discharge of a firearm, were for murder.

In mid-November, neighbouring Malaysia announced that it plans to scrap the death penalty for 32 offences, to be replaced with a minimum 30 years’ jail time if approved by Parliament.

On the developments across the Causeway, Mr Amrin stressed that every country “has the sovereign right to determine its own legal system, based on its specific context and needs”.

He added: “The Singapore Government regularly reviews the efficacy of our criminal justice system, including our penal laws and the applicable sanctions.”

Around the world, 106 countries — including Association of South-east Asian Nations members Cambodia and the Philippines — have abolished the death penalty for all crimes.

Thirty-six other countries retain the death penalty for serious crimes such as murder, but have either not executed anyone in the past decade or have made an international commitment not to use the death penalty.

Fifteen countries impose the death penalty for drug-related crimes, but according to human rights group Amnesty International, Singapore was one of four that recorded executions for drug offences in 2017. The others were China, Iran and Saudi Arabia.

Since 2008, the UN General Assembly has been debating on a biennial basis the question of a moratorium on the use of the death penalty, with a view to getting all member states, including Singapore, to abolish it.

DO S’POREANS CARE?

Ms Han, who co-founded We Believe in Second Chances in 2010, believes that Singaporeans’ lack of awareness on the death penalty is not because they do not care about the issue. Rather, she said, it is due to the difficulty in bringing the cases to the public’s attention.

Families of death row inmates usually approach activists like her only after they exhaust their avenues of help — that is, when their clemency pleas to the President have been rejected. However, there is a short window between then and when the execution is scheduled to happen

This makes it difficult for lawyers to file late-stage appeals, and reduces the time for death-penalty cases to gain momentum in the media and attract public attention, Ms Han argued.

In a 2016 survey on public attitudes towards the death penalty, which was conducted by the National University of Singapore, almost two-thirds of the 1,500 respondents said they either knew nothing or very little about the death penalty in Singapore.On the level of interest and concern about the issue, the respondents were split down the middle, with half saying they were either “not interested or concerned” or “not very interested or concerned”.

The survey concluded that a majority of Singaporeans supported the death penalty, Still, it found that when respondents were presented with scenarios of cases, particularly for drug trafficking and firearm offences, support for capital punishment dropped. Seven in 10 were in favour of the death penalty when asked about it in general terms, but it was “not an opinion held strongly or unconditionally”.

A separate poll of 1,160 respondents by government feedback unit Reach in 2016 also found significant support for the death penalty, with support especially strong for having the death penalty as the maximum punishment for those convicted for violent crimes such as murder, but less so for drug trafficking.For example, 80 per cent of the respondents felt that the death penalty should be retained, while 82 per cent agreed that it was an important deterrent which helped keep Singapore safe from serious crimes.

.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }Lawyer Sunil Sudheesan felt that most people have not put much thought into capital punishment as they would only do so if someone they knew or cared about was facing a death sentence.

Mr Sudheesan heads the Association of Criminal Lawyers of Singapore, which called for the removal of the mandatory death penalty in its submissions to the Penal Code review committee earlier this year.

While the lawyer thinks the death penalty should remain, he is against the mandatory death sentence. “I think it’s important for our judges to be given the discretion (to decide if death is the most appropriate sentence),” Mr Sudheesan said.

Given the low crime rates here, Singaporeans “seldom realise that a segment of society is drastically affected by the death penalty”, he pointed out. “If, for example, Singaporeans with poor relatives in Malaysia who have no choice but to traffic in drugs, they will definitely think about things (such as capital punishment),” he added.

However, humans right lawyer M Ravi, who has represented several people on death row in Singapore on a pro bono basis, believes that the conversation on the death penalty here “is very much alive”.

“I have not witnessed any such apathy from Singaporeans on the death penalty issue. In fact, the interest intensified during the execution of (Muhammad Ridzuan Md Ali) in May 2017, and even with the execution of Malaysian Prabagaran (Srivijayan) in July 2017,” he added.

About 17 people, including anti-death penalty activists like Ms Han and civil rights activist Jolovan Wham, held a candlelight vigil outside the prison in support of Prabagaran the day before he was hanged.

WHERE S’PORE STANDS

In Singapore, 32 offences are punishable by death. These include murder, drug trafficking, terrorism, and the possession of unauthorised firearms, ammunition or explosives.

In 2012, the Government amended the Misuse of Drugs Act and the Penal Code for certain types of homicide or drug trafficking cases.

Judges now have the discretion to impose life imprisonment or the death penalty on those who commit murder but did not intend to kill, as well as drug couriers who have either been certified by the public prosecutor to have substantively assisted the Central Narcotics Bureau, or have proved themselves to be mentally impaired. Previously, murder and drug trafficking offences carried a mandatory death sentence.

After these changes took effect in January 2013, all death row inmates were given the option to be considered for re-sentencing. Drug traffickers Yong Vui Kong and Subashkaran Pragasam were the first to be re-sentenced, to life imprisonment and 15 strokes of the cane each.

Some of Singapore’s death-penalty cases which have attracted much publicity involved foreign nationals.

One was Filipino domestic worker Flor Contemplacion, who was executed here in 1995 for murdering a fellow domestic worker and the three-year-old under the latter’s care. Her death strained diplomatic relations between Singapore and the Philippines for several years.

The case also sparked intense outrage in the Philippines against the Singapore Government, with demonstrations staged outside the Singapore embassy and Singapore flags burned. Then-President Fidel Ramos, who had personally pleaded to the Government for clemency, recalled his ambassador to Singapore.

In 2016, Sarawakian Kho Jabing, convicted of killing a construction worker, was executed following a rollercoaster bid to escape the hangman’s noose. His was the first case where prosecutors had challenged a court’s re-sentencing, following changes to the laws.

More recently, 31-year-old Malaysian Prabu Pathmanathan was hanged on Oct 26 for preparing and trafficking in 227.82g of heroin. His execution spurred fresh calls by human rights groups for Singapore to abolish the death penalty, with some reports saying there were four executions in that week alone. The authorities here usually do not comment on executions.

Singapore Management University (SMU) law don Eugene Tan, who spoke in Parliament about the death penalty while serving as a Nominated Member of Parliament from 2012 to 2014, said that Singapore’s position on the death penalty is “more nuanced than the abolitionists’ austere characterisation of an abiding commitment to the death penalty”.

The changes to the laws do not lessen the severity of murder and drug trafficking offences, the associate professor added, but mark a “subtle shift in the administration of criminal justice that strives for greater texture and nuance in the application of punishment”.

The law also requires that all death sentences be carried out only after a convicted criminal has two tiers of court review of the sentence, and that all people facing capital charges are provided adequate legal representation under the Legal Assistance for Capital Offences (Lasco) scheme, Assoc Prof Tan noted.

THE KEY QUESTION OF DETERRENCE

The death penalty is used only against “very serious crimes”, and has been an “effective deterrent” against them, Mr Amrin said.

For instance, the number of crimes committed with firearms fell sharply after the Government introduced the mandatory death penalty for such offences in 1973, while Singapore has one of the lowest murder rates in the world.

“The death penalty has deterred major drug syndicates from establishing themselves in Singapore. And this has helped to reduce the supply of drugs to Singapore,” Mr Amrin added.

In the 1990s, more than 6,000 drug abusers were arrested every year. That has now dropped to about 3,000 every year, even though Singapore’s population has grown, he elaborated.

During the Committee of Supply debates in March, Mr Shanmugam said the young are the “real victims” in the Republic’s war against drugs, rather than drug traffickers facing the death penalty. Such severe penalties serve to deter drug trafficking offences, and Singapore should not ease up on its commitment to deal with the drug problem, he added.Mr Amrin said: “The death penalty does not work on its own, but as part of the criminal justice system. To effectively deter against crimes, we also need a highly professional and incorruptible (police force) and Central Narcotics Bureau, which means that the probability of being caught is high.”

SMU’s Assoc Prof Tan noted that “deterrence (and retribution) remains the foundation of Singapore’s criminal justice system”, with capital punishment “still regarded as an effective tool in law enforcement”.

On the flip side, several experts said there have been no conclusive studies worldwide over the past few decades demonstrating that the death penalty is a sufficient deterrent to serious crimes.

Dr Wesley Kendall, an American legal scholar and senior lecturer at James Cook University Singapore who has studied and published articles on capital punishment, pointed to a criminology study conducted in 2010 that compared homicide rates between Hong Kong and Singapore.

Hong Kong abolished the death penalty in 1993, but the researchers found no statistical increase in violent crimes occurring over the following years, similar to Singapore.

While the study did not take into account drug trafficking, Dr Kendall said many other independent factors could have played a part in the Republic’s low rate of drug law violations, such as law enforcement officers cracking down on drug use, or new technologies used to detect traffickers’ activity.

“Even if there is a proven mathematical correlation between the decline in drug trafficking in Singapore, and the use of the death penalty (which has itself declined dramatically over the past 30 years in Singapore), there may not be a strong causal connection,” he added.

Assoc Prof Tan countered that there has also been no definitive study proving capital punishment does not work.

“What is clear is that capital punishment on the statute books and the level of enforcement do impact how a would-be criminal decides whether to commit an offence that carries the death penalty. The disagreements revolve around the level of effectiveness for capital punishment and whether the ultimate punishment is justified for whatever level of effectiveness,” he added.

Nevertheless, much of the research into whether the death penalty serves as a deterrent has been done by experts abroad, focusing on homicide. The experts TODAY spoke to agreed that not enough has been conducted in the region, especially on drug trafficking.

Dr Jeffrey Fagan, one of the researchers involved in the Hong Kong-Singapore homicide rates study, told TODAY that he will be seeking data on drug seizures and prices as he and his colleagues continue to assess the deterrent effects of executions in Singapore and the region.

Lawyer Eugene Thuraisingam noted that despite the tough anti-drug laws, 40 per cent of drug abusers arrested last year were new abusers.

And even with the shadow of the death penalty looming over them, Mr Sudheesan said that some drug traffickers still take the risk as they are “desperate”.

“The death penalty doesn’t scare them so much. If they were informed that every car at the checkpoint would be checked, then they would not offend,” he added.

Besides public surveys, Mr Sudheesan suggested that the Government conduct a survey of death row inmates to “try to find out the psychology of offending behaviour and what could have stopped them, because for some of them, the death penalty clearly wasn’t a deterrent”.

Ms Rachel Zeng, a campaigner from the Singapore Anti-Death Penalty Campaign, added: “We can totally afford to peel the layers of the onion and look deep into identifying factors leading to drug crimes in our society, and implementing longer lasting solutions to prevent and minimise drug abuse, which brings demands for drugs and hence the trafficking of drugs into Singapore.”

S’PORE SOCIETY TO DECIDE FOR ITSELF

While Malaysia is planning to abolish the death penalty, Assoc Prof Tan said it is “unlikely” that Singapore would follow suit in the next few years, as each country has to determine what works best for them.

“But the landscape is an evolving one, and Singapore will have to take note of international developments and norms and how public attitudes shift,” he added.

Nevertheless, Professor Michael Hor, the University of Hong Kong’s dean of law, said that should Malaysia abolish the death penalty for offences that attract a death sentence in Singapore, problems may arise when the Republic seeks its neighbour’s co-operation to return suspects who have fled across the Causeway.

Dr Kendall recommended the establishment of an “official commission” — comprising academics, lawyers, judges and other experts — to independently consider issues surrounding the death penalty. It could then submit a report to the authorities for further action.

For criminologists, lawyers and activists whom TODAY interviewed, the need for Singaporeans to increase their awareness on the subject — and for some, to end their apathy over it — boils down to one reason: Capital punishment is at odds with the sanctity of life.

Mr Thuraisingam — who has represented at least 17 people facing the death penalty, many of them under the Legal Assistance Scheme for Capital Offences scheme — said that Singaporeans should “take a good hard look” at the death-penalty regime when executions are carried out by the State, even if they or their loved ones are not involved.

They should also examine the arguments for and against it to decide if they can support capital punishment in good conscience.

“When it comes to matters of life and death, there can be no margin for assumptions and/or doubt. No matter where one stands on the issue, it is absolutely essential that we examine the death penalty through a principled and evidence-based approach,” he added.

Agreeing, Mr Sudheesan reiterated that the more society engages with a particular issue, the more it can inform policymakers on what the public really thinks of the issue.

Echoing the views of several experts interviewed, Dr Kendall said: “Whether it is time for Singapore to follow the path of other nations and consider abolishing the death penalty, it is a decision that can only be made by Singaporeans, within the best interests of Singaporeans, and designed to ensure the continued and future peace of the Singaporean state.”