The Big Read: As maids become a necessity for many families, festering societal issues could come to the fore

SINGAPORE — In less than a decade, the number of foreign domestic workers (FDWs) here has spiked about 27 per cent — from about 201,000 in 2010 to 255,800 as of June this year.

A foreign domestic helper is seen strolling with an elderly woman on Oct 31, 2019.

SINGAPORE — In less than a decade, the number of foreign domestic workers (FDWs) here has spiked about 27 per cent — from about 201,000 in 2010 to 255,800 as of June this year.

Now, every fifth Singaporean household hires a maid. In 1990, the ratio was about one in 13, with about 50,000 maids here then.

Amid rising affluence, a prevalence of dual-income parents and a rapidly ageing population, Singapore families’ dependence on FDWs is set to increase even further.

For many, hiring a FDW is no longer a luxury. It is a necessity. Take the case of the family whom Ms Zin Mar Kyi from Myanmar is working for.

The 28-year-old has not seen her own family in four years. But each time she brings up the idea of taking three days of leave to return to Myanmar to see her ailing father, her employers would decline, telling her that there would be no one around to look after the elderly at home.

Ms Zin Mar Kyi’s experience is not uncommon among FDWs making a living here. But it highlights just one of many issues plaguing the industry — issues that run the whole gamut but have been left unaddressed for decades.

And it is not just the FDWs who are facing problems. TODAY’s interviews with all stakeholders — agents, maids and employers — showed that each side has its own set of long-standing grievances, even as new challenges, such as the rise of social media, complicate the equation.

In recent months, there have been signs that if left unchecked, the underlying issues could lead to more serious problems.

For example, the Government recently highlighted the sharp spike in the number of foreigners — with maids making up a substantial proportion — borrowing from licensed moneylenders, from 7,500 in the whole of 2016 to 53,000 in the first six months of 2019.

Under tightened regulations announced in July, foreigners, including maids, who earn less than S$10,000 can now borrow only up to S$500 – S$1,000 less than when the rule was first imposed in November 2018.

Then, there is also concern over the radicalisation of FDWs, albeit in small numbers so far.

Since 2015, 19 FDWs have been found to be radicalised in Singapore. Three of the maids were charged in court last month with terrorism financing. The rest had been repatriated after the authorities completed their investigations.

While none planned to carry out violent acts on Singapore soil, the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) had previously said their radicalisation and associations with terrorists overseas made them a security threat to Singapore.

Experts including Dr Noor Huda Ismail, an Indonesian who is currently a visiting fellow at the S Rajaratnam School of International Studies, noted that in most of these cases, the radicalisation process stemmed from the FDWs seeking companionship and ended up being indoctrinated by online boyfriends.

While FDWs have recently been in the headlines for the wrong reasons including theft and attempted poisoning, they are often also at the receiving end, with cases of maid abuse regularly heard in the courts such as the one involving a couple who subjected two domestic helpers to repeated violent physical and emotional abuse.

TODAY takes a look at the longstanding issues faced by the different stakeholders as well as the implications, and what can be done to address them.

MAIDS’ CONCERNS — MONEY MATTERS AND PERSONAL FREEDOM

While most people have the luxury of checking out the work environment, scrutinising every line in their employment contracts or even stalking their bosses on social media, maids are not as lucky.

Not only do they know little about their bosses-to-be, it also does not help that their work visas bind them to their employers, giving the latter the power to terminate contracts at will.

Take the story of a Filipino maid who wanted to be known only as Beth.

The 53-year-old was let go just three days before her acute appendicitis surgery was scheduled in Singapore, and she suspected that her employing family was reluctant to pay S$12,000 in medical fees upfront before they could claim insurance to cover the costs.

When Beth first complained about a headache and a sharp pain in her abdomen after she was told to look after the baby, her female employer simply told her to “stop making dramas”.

The maid who was rolling in pain ended up getting checked at a Singapore hospital only after she called her neighbour’s helper, as her employer would only give her Panadol.

Beth returned to the Philippines with a S$400 flight ticket she paid out of her own pocket, as the one which her employers were obligated to pay for was handed to her just two hours before the plane was set to take off — the same time when she was abruptly told of her dismissal.

The 2013 incident was the lowest point in her 20 years of employment in Singapore, as she ended up having to spend 130,000 Phillipine pesos (about S$3,500) for the surgery in a Manila hospital, where she was admitted to the emergency ward.

Ms Maana Edquila, 47, who is also from the Philippines, said she would usually try to self-medicate when she feels sick, so as not to burden her employers.

She is also aware that her employers have bought some form of insurance plan for her but is not sure what it entails.

According to the Ministry of Manpower (MOM), employers are required to buy medical insurance plans with a minimum coverage of S$15,000 per year to help them manage their maids’ medical costs. The amount was raised from S$5,000 to S$15,000 in 2010 to keep up with the larger medical bills.

Money has indeed been the cause of headaches for many maids here. Many leave their homelands in search of a better life for their families, but before they can make any gains, most of them know they must suffer financial hardship in the first few months at least.

Almost all the maids TODAY spoke to knew they would have to pay placement fees – or “maid loans” – of about six to nine months. This is despite MOM’s law that allows Singapore agencies to deduct only two months of a worker’s pay for placement fees.

Many agencies here stressed that the rest of the placement fees are given to agencies in the maid’s native country, which cover pre-employment expenses such as the flight to Singapore, lodging, training and medical examination.

However, most of the maids interviewed did not know exactly what they were paying for. Among those who did, they felt that the training, food and lodging which they were given at the agencies back home were not worth the amount they paid.

Indonesian Ida Ayu, 24, said the living conditions in the Indonesian agency were “terrible” and “not even worth the six months’ deduction” of her salary.

Speaking in Bahasa Indonesia, she said that she stayed at the agency for over four months. There, she ate chicken only once a month. On good days, she got to eat seasoned vegetables or chicken heads and feet.

The sleeping quarters were also packed, with over 20 women “sleeping shoulder to shoulder on the floor'', she said. The experience was like “being in jail”, she added.

Some of the more resourceful maids said they were able to bypass their agencies back home to land a job in Singapore.

Among them was Indonesian Husnul Khotimah, 40. She left her village in Lampung for Singapore early last year and applied for a job as a maid at a Singapore-based agency.

Happy that she had to pay only two months of placement fees as she got the job at the agency of her own accord, the mother of two children, aged 20 and three, said: “I heard about the high placement fees that maids had to pay and I didn’t want to be in so much debt.

“Six months of salary deduction is a lot of money. I have kids at home to feed.”

But not everyone is as lucky as them.

Coming to a foreign land with modest finances and little English, Myanmar maid Chomden (not her real name) was abused by her employer merely three weeks after she started working.

The memory of the abuse brought tears to her eyes as she told TODAY through a translator that she was slapped and beaten with kitchen utensils every other day for more than a month.

Chomden later told a friend about what happened, and the latter lodged a complaint to MOM, which launched an investigation.

More than two years have passed and Chomden is still waiting for the case to be heard in court. She has been staying in a shelter run by non-governmental organisation (NGO) Humanitarian Organisation for Migration Economics (HOME).

HOME casework manager Jaya Anil Kumar said it is common for maids to stay in a shelter for an indefinite period, noting that the shelter is consistently near full capacity. The shelter helps about 800 FDWs each year, on average.

A larger shelter managed by the Centre for Domestic Employees (CDE) separately housed 373 maids last year, up from 141 in 2017.

Ms Jaya said that for more complicated cases, the entire process could take more than five years. This was so for Myanmar national Moe Moe Than, 32, who reported her abuse in 2012 but the trial involving her employers only concluded in March this year.

Although Chomden can be re-employed in the meantime, many Singaporean employers are hesitant to hire her after finding out that she is involved in a police investigation — never mind that she is the victim.

“A lot of the domestic workers themselves are quite traumatised by their previous experiences and they don’t want to go back to domestic work,” said Ms Jaya. “So due to the confluence of these factors, they just end up waiting for their cases to come to a conclusion.”

In response to TODAY’s queries on the incidence of such maid mistreatment cases, MOM said it “remained low” at an average of 40 cases annually between 2010 and the first half of this year. The cases comprise employers failing to pay salaries or not providing safe working conditions.

Over the years, MOM has introduced a series of new measures or enhanced existing policies to better protect the well-being of FDWs.

These include amending the Employment Agencies Act in 2011 to cap the fees which the agencies can charge FDWs, and to impose higher penalties for unlicensed and errant agencies. In 2013, MOM also introduced mandatory weekly rest days or compensation-in-lieu. The minimum sum assured under FDWs’ personal accident insurance was also raised in 2017 from S$40,000 to S$60,000, which will accrue to FDWs or their families.

According to MOM’s 2015 survey of 1,000 FDWs, 97 per cent said they were satisfied working in Singapore while 76 per cent said they intended to continue working in Singapore upon

completion of their current contracts. The next periodic survey will be conducted in 2020, MOM said.

SMARTPHONES — A MAID’S ‘LIFELINE’

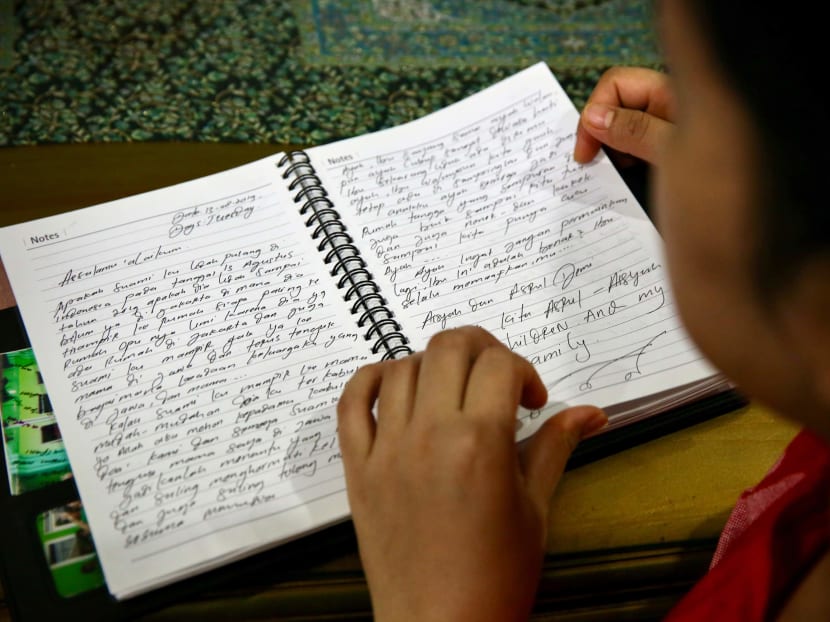

Thousands of miles away from home and not being able to go out as much as they like, many maids have turned to the internet and social media as an important outlet for recreation and to stay connected with friends and families, as well as the outside world.

They can video call their family, or post updates on social media applications such as WhatsApp, Telegram, Facebook, and Instagram. To cure their boredom, some of them have also turned to video-sharing applications like TikTok.

On TikTok, it is quite common to see maids dancing or mouthing lyrics as they go about doing household chores such as feeding a baby or cooking.

Earlier this week, Filipino maids Florence Suyo, 39, and Evelyn Balnez, 38 — both of whom had been working in Singapore for close to 20 years — were vlogging along Orchard Road.

They told TODAY that they also use their smartphones to coordinate days-off, and stay connected to a Taekwondo master whose classes they attend — along with 20 other maids — every weekend at Nee Soon Community Centre to keep fit.

“Phones are the only (lifeline) of the helper,” Ms Suyo said. “If the employers won’t allow their helper to hold the phone, you cannot get along with the helper because phones are the connection with the family.”

But maids here are not immune to the dangers lurking on the internet and social media.

In particular, some maids’ quest for companionship online has seen them fall victim to scams and radicalisation. The number of radicalised maids remains small, with 19 cases coming to the authorities’ attention in the past four years.

Responding to TODAY’s queries, MHA said it has seen around two to five cases per year since 2015. Among the 19 cases so far, only one was reported by the employer while the rest were picked up following investigations by the Internal Security Department.

The cases involved maids who had worked here for periods ranging from several months to 14 years. None of them harboured any intention to carry out acts of violence in Singapore.

In most cases, they were in contact with friends who were also working as maids in Singapore, so there was no indication that social alienation was a contributing factor to their radicalisation, said MHA.

Instead, many had fallen prey to propaganda by militant group Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS) after befriending pro-militant online contacts, including online “boyfriends”, the ministry noted.

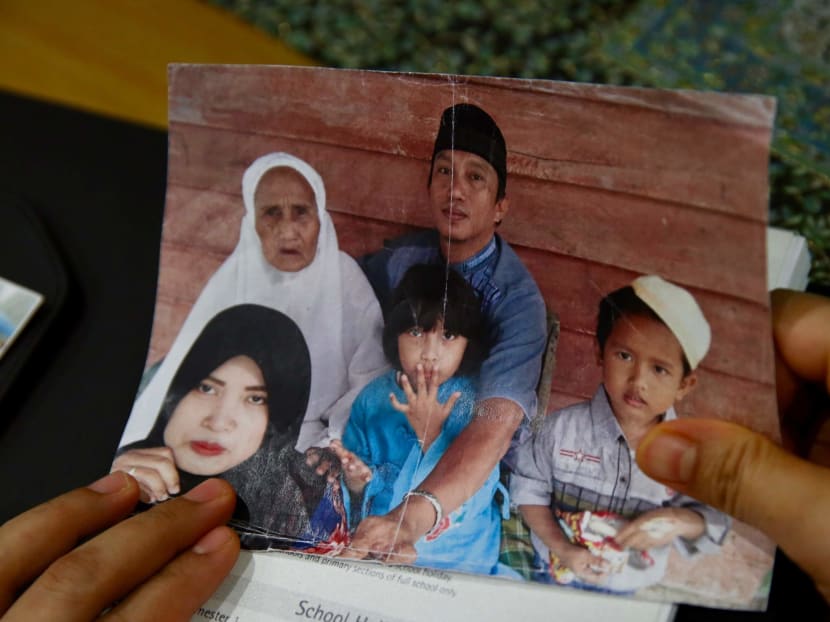

Dr Huda, who had produced a documentary of three Indonesian maids who became radicalised, called such relationships “love scams”.

One of the maids featured in his documentary titled Pengantin (Indonesian for “bride”) was Dian Yulia Novi, who used to work as a maid in Singapore in 2008 and 2009. The then-28-year-old became radicalised through Facebook while working in Taiwan, where she started preparing to be a suicide bomber “bride”.

She married a pro-ISIS militant whom she met online, and was arrested and jailed 7.5 years for plotting to blow herself up outside Jakarta’s presidential palace in 2016.

ISIS recruiters typically target individuals through general platforms such as Facebook in the initial stage, said Dr Huda.

Subsequently, the individuals are added into WhatsApp groups, before being lured into one-on-one conversation on Telegram where messages are encrypted.

Generally, maids could be a target as they are “economically and socially marginalised” individuals living apart from their family nucleus with little education and digital literacy, Dr Huda said.

In 2017, following the news that the authorities had picked up radicalised maids, MOM and MHA sent an email to employers asking them to look out for indicators of radicalisation, such as an “avid reading of radical materials”.

In its response to TODAY, MHA noted other traits including drastic changes in appearance or behaviour such as in dressing, living habits, becoming withdrawn from those who do not share similar ideology or views, and espousing an “us versus them” thinking.

‘TOUGH TO FIND A GOOD MAID’: EMPLOYERS

Based on MOM statistics, two in three maids do not complete their two-year contracts, with 250 employers changing maids five or more times within a year in 2018.

At first glance, the figures seemed to suggest that the employers here are too picky. But interviews with several employers who had changed maids several times within a short span presented a different story.

For example, a 31-year-old sales manager, who wanted to be known only as Ms Tan, said that she had encountered “all princesses” after her trusty Filipino maid of two years returned home when her contract ended in 2016.

The mother of three — who ended up changing seven maids within 1.5 years — caught one helper on surveillance camera lying stretched out on her sofa and using her face mask while her family was away on holiday, even when she had been given tasks to complete.

Two other replacements were “tai-tais”, she said, including one who took taxis whenever she headed out.

A 43-year-old manager in a private equity firm, who declined to be named, similarly had to change six helpers between 2015 and 2018, after losing a long-time Indonesian helper who wanted to return home to take care of her mother.

“They are just here for play and fun, demanding a lot of things from the get-go,” said the mother of three. She said that she used about S$15,000 of her savings to transfer the maids out, before her former Indonesian helper agreed to return in August this year.

Ms Tay Mui Lan, 29, owner of a cafe in the East Coast area, said she had spent about S$10,000 over the past six months changing five maids — all of whom did not want to work for her household of five.

They came up with all kinds of “drama” after getting assigned to her family’s home, a four-storey terraced house in Serangoon.

One “purposely” did things that frustrated her, such as scratching her floor and car and cooking for two instead of four, as if to spite the family, said Ms Tay.

Based on her observations, Ms Tay felt that the maids were “picky”, adding that her demands were not unreasonable — changing the bedsheets once every month, and ensuring that dirty laundry was not piling up. She added that she did not ask for all four floors to be cleaned daily.

“I don’t understand why I cannot get a helper (who sticks around). Maybe I am too nice,” she said.

Some of these complaints are echoed in an online petition put up in July, asking MOM to “get tough” on errant FDWs and maid agencies, and enact laws to protect employers.

Signed by more than 700 employers, the petition says that employers have been “suffering in silence”. Among other things, it notes that maids are not penalised and do not have to bear any cost when they ask for transfers.

“No wonder more and more FDWs (are) becoming increasingly brazen, demanding and bold in their demands,” says the petition, citing demands such as free Wi-Fi access, days-off during public holidays on top of weekly days-off, and private bedrooms.

On its part, MOM said that FDWs who commit offences in Singapore will be “punished and banned” from working in Singapore. Between 2010 and the first half of this year, the ministry took action against an average of 60 FDWs per year for breaches under the Employment of Foreign Manpower Act, such as working without a valid work pass and false declaration in employment.

EMPLOYMENT AGENCIES: THE BOGEYMAN

As for issues regarding the recruitment of maids, maids and their employers have blamed the middlemen — employment agencies — for not being transparent with their contracts.

In response, Ms K Jeyaprema, who is the President of the Association of Employment Agencies, pointed to maids who lie about their age and work experience, and employers who are not truthful about the actual number of people living in their households and what they indicated as the maids’ job scope.

On the issue of placement fees, she said that there are so many miscellaneous expenses in the process of bringing in maids to Singapore that it is difficult to keep track of every dollar and cent.

While agencies are obliged to compile an itemised receipt, breaking down all expenses which the maid is paying for, she said that some agencies could be “massaging” some figures on vague-sounding components such as service fees.

To address this, MOM said it conducts regular audits on agencies to ensure compliance. Last year, the ministry took action against two errant agencies. The law provides for such agents to be fined up to S$5,000, jailed for up to six months, or both.

MOM reiterated that the Employment Agencies Act states that agencies here cannot charge more than two months of a foreign worker’s salary, and no more than one month for each year of service as agency fees.

Agencies must also refund at least half of the agency fees collected from workers who are prematurely terminated within the first six months of employment.

As for the agencies’ accountability to employers, MOM had announced earlier this month that from October 2021, agencies will have to provide an option for a refund of at least half of the service fee charged to employers when the employment contract ends prematurely.

“This will ensure that the (agencies) take greater ownership in finding suitable and better matches for employers,” MOM had said earlier.

Further measures to improve poor maid retention rates include providing employers access to a maid’s employment records, such as her key job scope, residence type and household size, and reason for leaving her last employment.

Mr John Gee, president of non-profit organisation Transient Workers Count Too (TWC2), suggested that maids should be given access to similar records about their potential employers, including how many maids they have hired within a certain period of time.

MOVING FORWARD

While the placement fee issue appears to have reached an impasse, as it requires cross-jurisdiction intervention, NGOs here are pushing for maids to be covered under the Employment Act, instead of the Employment of Foreign Manpower Act which they are currently under.

Mr Gee said the Employment Act, which sets limits on working hours among other things, would provide for overtime pay and better regulate maids’ overall terms of employment.

Agreeing, HOME’s Ms Jaya pointed out that domestic helpers here work about 14 to 16 hours on average a day. Their rest time during the day is subjected to constant negotiation with employers, she added.

Ms Jaya said the well-being standards in the Employment of Foreign Manpower Act are less stringent than those stipulated in the Employment Act. “(The former) states that (domestic helpers) should get acceptable accommodation and adequate rest and food, but these often get left up to the employers to determine,” she said.

When push comes to shove, MOM guidelines are “not legally mandated”, she said.

For example, under the guidelines, “adequate food” for a maid for one day consists of four slices of bread with spread for breakfast, one bowl of rice with three-quarter cup of cooked vegetables, a palm-sized amount of fish, poultry, beef or lamb, and a fruit each for lunch and dinner.

But during enforcement, a maid’s weight is often used to determine if she is underfed — and this may not reflect accurately her food situation, said Ms Jaya.

While there is no silver bullet for the litany of issues in the industry, observers noted that much of the problems revolve around the live-in arrangement for maids.

MOM has been piloting since 2017 a scheme allowing work permit holders, which include former full-time maids from countries such as India, Myanmar, Sri Lanka and Thailand, to provide part-time domestic services instead.

Previously, only work-permit holders from Malaysia, China and other source countries in North Asia can be brought in as service workers who are deployed to multiple households and do not live in the households where they work.

Twenty-five cleaning companies are part of this scheme including on-demand home services platform Helpling.

The firm has conducted a survey on former live-in maids who have converted to part-time work under the pilot scheme.

- Based on the findings, almost all (97 per cent) of the 174 respondents said they preferred the part-time arrangement, compared with living with their employers.

- 80 per cent of the respondents said they were happy to be able to completely relax after work — instead of having to look busy even after they had completed their tasks as live-in maids.

- 38 per cent were happy to have their own personal space and the freedom to choose what to eat.

Helpling said that under the pilot part-time scheme, the FDWs have “a dignified life that is fully within their control”. This leads to higher productivity, “motivating them to work harder and earn more in the process”.

It added: “Furthermore, as proper employees with basic worker rights, the helpers are able to walk away from customers whom they feel may be rude, reasonable or abusive.”

Another firm participating in the pilot is @bsolute Cleaning. Its manager Daegan Tan, 37, said the helpers are paid S$900 to S$1,000 a month. They will look for and pay for their own lodging but the firm provides them with a S$200 monthly subsidy for rent. They are also given S$300 for transport each month. Their working hours are generally from 8.30am to 6.30pm, with a two-hour break in between.

Mr James Lim, Helpling’s Asia-Pacific managing director, said that the salary which FDWs make as part-time cleaners is at least 50 per cent higher than what they got as live-in maids.

Helpling’s team of 200 cleaners take up more than 10,000 jobs each month. On average, a part-time cleaner takes up to 60 jobs at 25 different households each month, Mr Lim said.

Myanmar national Phyo Phyo Ei, 35, a former live-in maid who now works as a part-time cleaner, told TODAY that out of the three employers she had had over nine years, two did not provide her with proper meals.

She had found out about the pilot scheme on Facebook. Her work now is “more relaxing” and does not require her to be “on standby 24/7”, she said.

Mr Rio Goh, director at Ministry of Clean, pointed out that a part-time arrangement is also ideal for employers who are uncomfortable with having a maid living with them and being alone in their house while family members are out.

However, the part-time arrangement would not meet the needs of families who require constant care for young children or elderly members of the household, for example.

Ms Mazidah Musa, a 53-year-old housewife who lives with her 85-year-old dementia-stricken mother, said she would need someone “who will be there to constantly keep an eye on my mother”.

She noted that currently, her maid’s work is not complete after putting her mother to bed. Sometimes, in the wee hours, her mother might have to use the toilet and their maid who sleeps on a mattress beside her mother’s bed would have to help with that.

Likewise, those with young children said they need help at night when they work late or early in the morning to prepare them for school, for example.

For many Singapore households, there remains a genuine need for live-in domestic help. And the number of such families is set to rise, given the demographic and social trends. This means that all stakeholders and policymakers would have their work cut out to resolve the longstanding issues.