Asean faces more risks as summit season ends

Unsurprisingly, the 33rd Asean summit was overshadowed by the bigger challenge of how to handle the US, China and their brewing trade conflict that could widen. That Asean's summit season this year has ended with a whimper and acrimony bodes ill for what lies ahead. The US-China superpower face-off is now the most pressing and daunting challenge of our times.

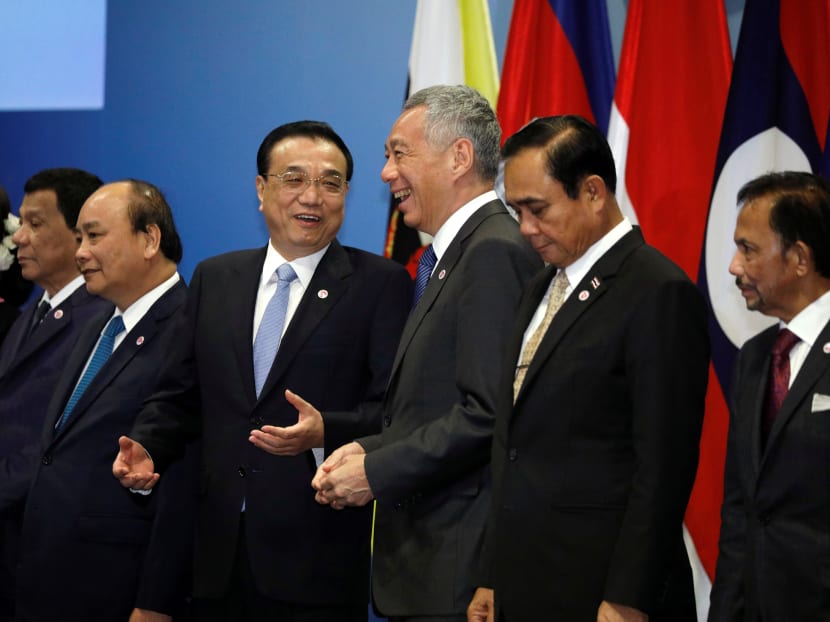

China's Premier Li Keqiang poses for a group photo with Asean leaders at the Asean-China Summit in Singapore on November 14.

The prominence and utility of the Association of South-east Asian Nations (Asean) as a regional platform for peace and prosperity is demonstrated most vividly in a series of top-level meetings among its leaders and counterparts from other major powers, particularly the United States, China and Japan, among others.

That Asean's summit season this year has ended with a whimper and acrimony bodes ill for what lies ahead.

As the Asean Chair in 2019, Thailand should feel more pressed and incentivised to get its house in order with an elected government that can function effectively before major Asean meetings get under way next year.

While the 13th East Asia Summit (EAS) in Singapore should have been the headline meeting, as was the case in the past because this grouping of 18 countries include the US, China, Russia, Japan, India, South Korea, Australia and New Zealand apart from the 10 Asean member states, this was not the case.

Instead, the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (Apec) in Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea, stole the show in a controversial fashion.

At issue beyond the pleasantries and pomp at the EAS was the ongoing trade conflict between the US and China on the one hand and their strategic rivalry through the US-led Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP) and China's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

The so-called "trade war" between the two largest economies in the world, one the preeminent global power in relative decline but intent on revival and the other an incoming superpower keen to assume its rightful place on the global stage, has deteriorated to a point of open confrontation. In a short span under President Donald Trump and President Xi Jinping's watch, the US and China are no longer just rivals and competitors but outright adversaries.

The US-China superpower face-off is now the most pressing and daunting challenge of our times.

For Asean, this means having to come up with an answer to the FOIP. Indonesia has led the way by calling for an "inclusive" FOIP as a building block of a broader Asean-based regional architecture with a focus on transparency, peace and stability.

Unsurprisingly, the 33rd Asean summit was overshadowed by the bigger challenge of how to handle the US, China and their brewing trade conflict that could widen.

Asean's attempt to propel the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership as the next-generation free-trade liberalisation vehicle did not go far. Tensions abounded as the stage was set for the Apec summit.

President Xi happened to be on a state visit to Papua New Guinea right before Apec. Some saw it as a manoeuvre to upstage the 21-member Asia-Pacific economic grouping, while others viewed it as par for the course in China's expanding tentacles in the Pacific Islands.

Nevertheless, the Apec summit ended without a joint statement for the first time since it was formed in 1989. The lack of even the lowest common denominator for a joint statement was attributable to the US-China war of words and opposing geostrategic posture.

Ironically, China assumed the stewardship of the post-World War II rules-based international order, which the US was instrumental in putting together.

In his Apec speech, President Xi called for the "need to advance economic integration" and to "promote trade and investment liberalisation and facilitation" while warning against "protectionism and unilateralism", which was undoubtedly a veiled reference to the Trump administration escalating tariffs throughout 2018.

In turn, US Vice President Mike Pence called out China's hypocrisy in benefiting from the open global trade regime while not opening up its economy, engaging in intellectual property theft and forcing foreign firms to share technological innovation.

Speaking on behalf of President Trump, Mr Pence said "China has taken advantage of the United States for many years" and that "those days are over".

In addition, Mr Pence took a swipe at China's BRI, pointing out that "we don't offer constricting belts or a one-way road," an explicit critique of the BRI's infrastructure loans and alleged debt entrapments among poorer economies.

Mr Pence also reiterated the US resolve to ply international waters in the South China Sea where China has constructed and weaponised a string of artificial islands.

Next year, the US freedom-of-navigation operational patrols (Fonops) are likely to increase and challenge China's maritime expansionism.

Moreover, the US is likely to peddle FOIP harder in the coming months to keep China's in check, offering more aid and development programmes to match up to China's BRI. In response, China will likely accelerate its BRI programmes and focus on its naval build-up to keep pace.

For Asean, all of this is bad news.

Asean was set up in 1967 to maintain regional autonomy and keep the major powers from dominating the region. Back then, it was the US-Soviet Union confrontation, this time it is between the US and China.

Generally, some tension short of open conflict between the US and China allows Asean to have leverage with these two superpowers. But when the US and China start to treat each other as adversaries, the region is in trouble.

The next few years will be critical for Asean to maintain its central role and regional relevance. Indonesia's lead in calling for an inclusive FOIP is a good start.

Asean should build a consensus around it, and try to incorporate the FOIP and the "quad" countries (US, Japan, Australia and India) into Asean-centred regional architecture-building like the EAS and Apec.

As China is being pressed by a global pushback against its BRI and preoccupied by the trade war, this is a good time for Asean to press China on a rules-based Code of Conduct for the South China Sea.

That China's regional assertiveness is being checked by the US bodes well for Asean's bargaining position.

There will be criticisms that Asean is ineffectual and inert -- good at holding meetings but getting nowhere.

But Asean's utility and reason of being are now more compelling than otherwise.

Without the Asean-centred cooperative architectural vehicles as buffer, the risks of a clash between the US-led FOIP, Fonops, and trade war on one hand and China-backed BRI, South China Sea weaponised islands on the other will grow.

Thailand, as incoming Asean chair, should seize this opportunity and take its own risks by trying to lead Asean and convince the two superpower antagonists to both back off. BANGKOK POST

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Thitinan Pongsudhirak teaches international relations and directs the Institute of Security and International Studies at Thailand’s Chulalongkorn University.