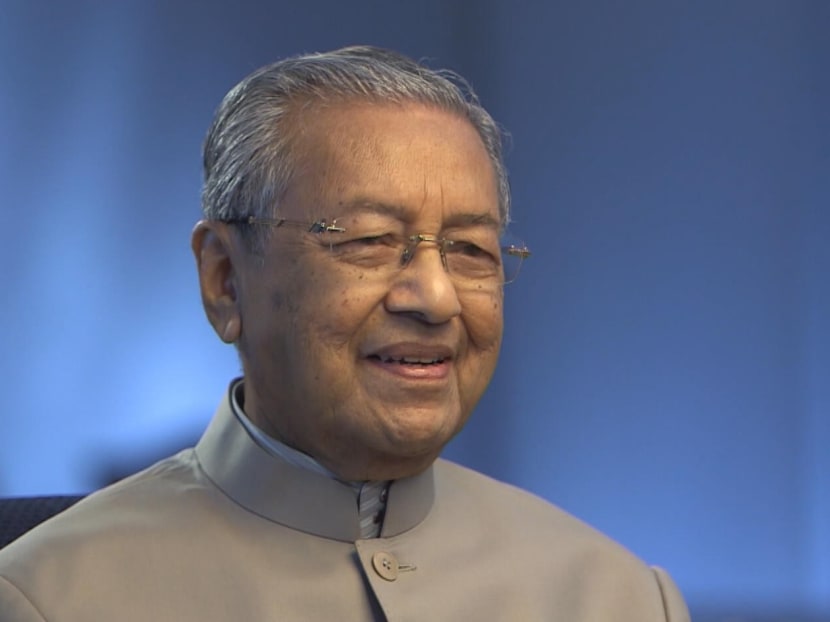

GLCs and patronage: Understanding Mahathir’s position on HSR and ECRL

Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad’s move to defer several mega infrastructural projects with Singapore and China has dominated headlines recently. Some observers have taken these announcements to mean that Malaysia’s relations with China and Singapore may enter a phase of heightened uncertainty. This assessment is perhaps premature. While worries over Chinese debt diplomacy may certainly factor into the Pakatan Harapan (PH) government’s calculations, Dr Mahathir’s decision-making is fundamentally driven by a domestic logic.

Dr Mahathir’s actions must be contextualised within the structure of the Malaysian political-economy – one that for six decades has been dominated by intimate relationships between business and political elites.

Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad’s move to defer several mega-infrastructural projects has dominated headlines recently.

These projects include the High Speed Rail (HSR) between Kuala Lumpur and Singapore, the China-backed East Coast Rail Line (ECRL) from Kelantan to Port Klang in Selangor, and the natural gas pipelines in Sabah.

Some observers have taken these announcements to mean that Malaysia’s relations with China and Singapore may enter a phase of heightened uncertainty. This assessment is perhaps premature.

While worries over Chinese debt diplomacy may certainly factor into the Pakatan Harapan (PH) government’s calculations, Dr Mahathir’s decision-making is fundamentally driven by a domestic logic.

Even Malaysia’s official position – that these projects are prohibitively expensive – does not paint the full picture. The PH government’s actions must be contextualised within the structure of the Malaysian political-economy – one that for six decades has been dominated by intimate relationships between business and political elites.

Leading Malaysian economists Dr Edmund Terence Gomez and Dr Jomo Kwame Sundaram have produced multiple in-depth analyses of the mutually beneficial relationships between political and business leaders throughout post-independence Malaysia.

They have studied Government Linked Investment Companies (GLICs) and Government Linked Companies (GLCs), through which the government intervenes in the economy.

After Dr Mahathir came to power in 1981, GLICs such as Lembaga Tabung Haji, Permodalan Nasional Berhad and the Minister of Finance Incorporated took controlling stakes in virtually every major sector of the economy – banking, finance, media, energy, construction, property, agriculture – by either incorporating new companies or becoming majority shareholders of private entities.

Prominent examples include CIMB Bank, Malaysian Airlines, Federal Land Development Authority, and Sime Darby. Newer GLICs such as Khazanah and the Employees Provident Fund were established in the 1990s to expand the government’s economic clout.

Today, the Malaysian government is the largest shareholder in 71 publicly listed GLCs. It also owns shares in another 286.

Through their GLCs, Malaysia’s seven GLICs control an astounding 42 per cent of the market capitalisation (i.e. value) of the entire Bursa Index, the Malaysian stock exchange. It is not clear how many unlisted GLCs exist.

Because these companies are located in critical and lucrative sectors, each administration sought to establish control by institutionalising systems of patronage.

People appointed to head GLCs and GLICs have been linked to the leadership – as family members, as close friends, as important associates, as reliable party members, or as loyal former civil servants.

Each PM organised Malaysia’s corporate structure to ensure important directors and key decision-makers at most levels of the economy were loyalists – either directly to them, or to leadership’s allies.

GLCs have also generally been granted favourable business contracts through Malaysia’s notoriously opaque tender system.

Importantly, Dr Gomez has also found that the fortunes of a given company – whether it is a GLC or not – is correlated to its relationship with the political leadership.

For this reason, Malaysia ranked second on the Economist’s 2016 Crony Capitalism Index, behind only Russia.

Over 97 per cent of Malaysia’s billionaires have actively benefited from intimate ties to political leaders.

Herein lies the reason Dr Mahathir has chosen to defer major infrastructural projects, including HSR.

Beyond a line linking the Malaysian capital to Singapore, HSR also includes plans for a secondary domestic railway with multiple proposed stations from Johor through to KL.

Inevitably, the construction of these lines will have spillover projects, including the construction of new townships, which will in turn require banking and financial services, road and transport networks, energy and utility supplies, retail outlets, etc.

Currently, those positioned to benefit from these business opportunities will, more often than not, be close to former Prime Minister Najib Razak.

Indeed, of the four Malaysian companies initially announced for HSR, three are GLCs (Malaysian Resources Corporation Berhad, Gamuda Berhad, and TH Properties), while the one non-GLC (YTL Corporation) has directors believed to be close to the previous Najib administration.

Notably, the government also possesses a substantial minority shareholding in YTL Power, a subsidiary of YTL Corporation.

Dr Mahathir has little interest in giving Najib ’s allies business opportunities.

Even if certain directors were never allied with Najib, Dr Mahathir would prefer to err on the side of caution first.

Deferring projects such as HSR and ECRL gives him time to identify and remove those whose loyalties subtly remain with Najib.

It is also possible that Dr Mahathir may wish to either restructure or reform the complex web of corporate networks which has hitherto enabled previous leaders, himself included, to reap the rewards of patronage.

Talk that Dr Mahathir will retain his confidante, Daim Zainuddin, beyond his tenure in the Council of Eminent Persons is instructive.

Mr Daim was instrumental in creating the government-corporate nexus in Malaysia during Dr Mahathir’s first reign. He is therefore best placed to understand, propose, and spearhead policy changes concerning this.

Dr Mahathir is unlikely to be against HSR or the spillover projects. His chief concern may also not be the country’s debt as he proclaims, but who will stand to gain from these projects.

Even his initial insistence that HSR would be cancelled was tactical rather than brash. He wanted to force investor pessimism onto companies involved in the project.

And right on cue, the stock prices of Malaysian Resources Corporation Berhad, Gamuda Berhad, and YTL Corporation fell sharply.

Dr Mahathir’s moves are therefore fundamentally about fixing the structure of the domestic political-economy.

To do so, he had to fire a warning shot at GLCs and major companies led by Najib’s loyalists.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Prashant Waikar is a research analyst at the Malaysia Programme in the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University.