How decentralisation and tokenisation could revolutionise society

Mike Winkelman set the world record for the most expensive non-fungible token (NFT) to date when he sold a digital stitchwork on Christie’s for US$69 million.

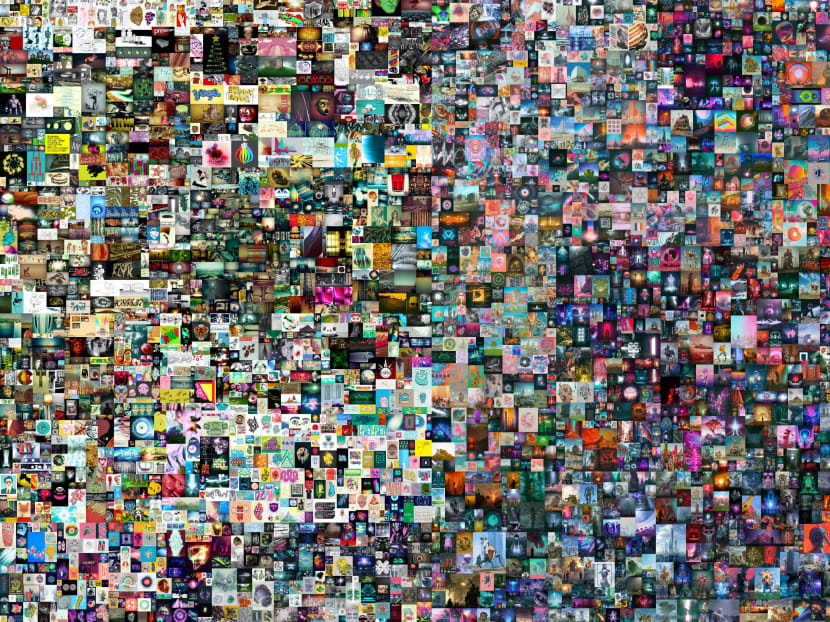

Digital collage Everydays: The First 5,000 Days by Mike Winkelmann, also known as Beeple, was sold as a non-fungible token for a record US$69 million.

Mike Winkelman set the world record for the most expensive non-fungible token (NFT) to date when he sold a digital stitchwork on Christie’s for US$69 million.

The sale attracted international attention not simply because of its price but the fact that someone was willing to pay top dollar for a non-physical JPG file that can be copied, downloaded, and viewed by anyone.

These debates aside, significant in the record-smashing sale is the underlying technology of decentralisation and tokenisation.

These two technologies enable NFTs as tokenisation converts virtual and physical assets into tradable digital units on the blockchain, which is decentralised in nature, thus ensuring public, inviolable proof of ownership and authenticity.

In that way, beyond the niche world of NFTs, some have wagered that a “decentralisation-of-things” and “tokenisation-of-things” will usurp the “internet-of-things” over the course of the next decades.

Such a vision, if realised, will have far-reaching consequences for societies around the world.

DECENTRALISATION-OF-THINGS

One of the most important real-world applications in decentralisation-of-things are decentralised autonomous organisations or DAOs.

These are entities that are programmatically leaderless, anonymous, and decentralised.

In simple terms, DAOs are organisations that are governed by programming language and can function autonomously without human managerial activity and without interference from any governments.

This is contrasted with traditional organisations that must comply with local laws and involve delegating decisions to key agents who might act against the organisation’s interests.

The latter problem is what economists term the “principal-agent” dilemma.

DAOs promise to solve this problem since they do not have chief executive officers or managers to steer the organisation; instead, members self-govern and vote collectively on all decisions which are immutably recorded unto the blockchain ensuring tamper-proof bookkeeping.

DAOs already exist in the fields of finance, art, insurance, and human resource.

One example would be Nexus Mutual — a DAO that provides insurance against hacking and smart contract failure.

Through Nexus Mutual, anyone can add funds to underwrite insurance policies to earn fees.

Significantly, all policy claims are deliberated and passed by the DAO collectively on the blockchain — there are no managers to process claims.

Members of this DAO are incentivised to ensure valid claims are paid out so they can attract customers to receive insurance fees.

This demonstrates how members are guided to act in the best interests of the organisation.

Another example is Yearn Finance — a decentralised finance aggregator — which implemented the DAO model in human resource through “governance weighted salaries”.

In contrast to workers receiving a relatively fixed wage, employees distribute “points” to team members they have worked with in the previous month.

This creates a salary scale that is weighted towards employees with the highest peer-evaluated contributions and these points are, in turn, cashed out as salary payments at the end of the month.

This radical refashioning of payrolls is experimental and obviously not perfect.

Nevertheless, the DAO model could potentially be more equitable and less costly in paying employees by eliminating human resource departments and liberalising compensation evaluations.

Naturally, legal questions, particularly those on liability, will be asked.

In that regard, regulation is catching up to DAOs. For example, Wyoming’s state senate passed a law to accord legal personalities to DAOs.

While DAOs are still in their infancy, the possibilities of mature DAO systems are immense and potentially revolutionary — it would fundamentally flip hierarchical organisations as we know them, with DAOs’ promise of efficiency, genuine participation, and cost-savings.

Politically, DAOs would be a libertarian’s dream as they carve an embryonic pathway towards leaderless governments and, perhaps, decentralised international organisations — realising participatory democracy in its idealised form.

Because of the pandemic, Singapore is having intense discussions on how persistent disruption; AI adoption and remote working will shape the future of work and transform the workplace.

DAOs ought to be part of this conversation as they are uniquely suited to produce organisational models and incentive systems that fit into the broader movement of flat, non-hierarchical work structures of the future.

TOKENISATION-OF-THINGS

Working hand-in-glove with decentralisation is tokenisation where tangible/non-tangible assets are converted into virtual “tokens” on a blockchain.

Just like DAOs, plenty of use cases exist.

Andy Warhol’s 14 Small Electric Chairs (1980) series was successfully tokenised and sold on the blockchain in 2018 — with 31.5 per cent of the painting sold for over US$1.7 million to various owners.

This opens the possibility of small investors owning precious pieces of art that is verifiable, tamper-proof, and highly liquid. Intangibles such as “status” can also be tokenised.

BitClout, a social-crypto platform run anonymously, tokenises influencers’ “clout” — allowing verified influencers control over their image and influence, without involving agents or third parties.

Yet, this is not without controversy. Indeed, BitClout had to remove Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong’s name and photo after he called the platform “misleading” for using his Twitter profile without permission for the purpose of tokenising his “clout”.

The tokenisation of assets has, sometimes, led to exceptional ends.

For instance, “eight lots” of virtual land were sold for US$1.5 million worth of cryptocurrency in the gaming platform, Axie Infinity.

While there is no doubt that there is a speculative element, the buyer justified his purchase on the grounds of tapping “the rise of digital nations with their own systems of clearly delineated, irrevocable property rights”.

Tokenisation could prove to be a profound creative force — allowing individuals to create, tokenise and trade literally anything outside of governmental supervision.

RE-CENTRALISE EVERYTHING

The tokenisation-of-things and digitalisation-of-things present precisely the sort of condition that governments will have to increasingly contend with, as these forces begin to invert power dynamics of state-society relations.

Even so, it is the instinct of governments everywhere to retain and preserve control.

In response to these developments, we are witnessing attempts by state actors to re-centralise - undermining the ethos of the decentralised, immutable, and anonymous quality of blockchain technology.

In that way, even as the implicit intent of these technologies and the products therein have a liberal bent, it is ultimately an agnostic tool that can be used for very illiberal ends.

The clearest case in point would be China’s rapid roll out of a Centralised Bank Digital Currency (CBDC).

While Beijing is retaining the sophistication of the underlying blockchain technology to build its digital yuan, it is nevertheless a centralised, controllable, and non-anonymous currency — subverting the raison d'être of cryptocurrencies.

MANAGING RISKS, SEIZING OPPORTUNITIES

State actors are not passive observers idly standing by as technological forces sweep over society.

Singapore, already a relatively crypto-friendly location, can do more to seize opportunities and manage threats in a tokenised and decentralised future.

First, there is a pre-emptive but urgent need for regulatory and normative clarity regarding decentralised entities and the tokenisation-of-things.

Having clear regulatory frameworks that are accommodative and supportive but not disruptive to innovation can help Singapore position itself as a leader in these areas.

This can, in turn, be parlayed into the international arena, to help configure rules, norms and ethics on such technologies.

Second, there should be greater cooperation at the regional level.

Despite the presence of regional mechanisms such as the Asean Free Trade Area, Asean Investment Area and the Asean Connectivity 2025 roadmap, there is no coherent, strategic plan to manage the opportunities and challenges that these twin processes would provoke.

Finally, while there is no shortage of technical experts — computer scientists, web developers, cryptographers and so forth — there is a need for greater investment in developing ethicists, futurists, and artists to imagine, interrogate and examine blockchain technology, cryptocurrencies and what such a future ought, should and could look like.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Dylan M H Loh is an assistant professor at the Public Policy and Global Affairs Division, Nanyang Technological University (NTU). He received an NTU-Ministry of Education research grant to investigate the socio-political effects of cryptocurrencies and blockchain technology.