How to navigate ethical issues of AI and Data

Earlier this month, Minister for Communications and Information S Iswaran announced the formation of an Advisory Council on the Ethical Use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Data. The council could not have come at a more timely moment, given the rapid developments in AI and Big Data in recent years.

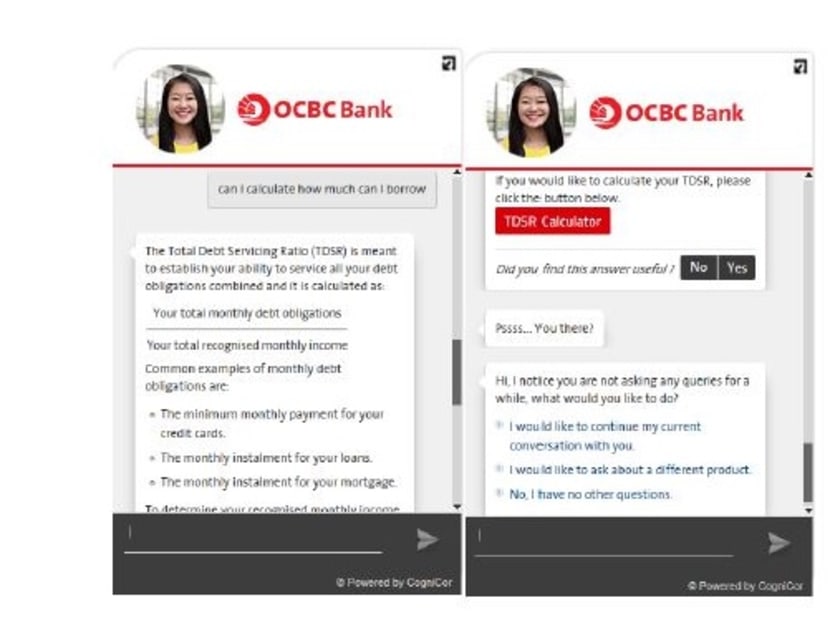

OCBC's AI-based automated chat system called Emma and works out home loans all without human intervention.

Earlier this month, Minister for Communications and Information S Iswaran announced the formation of an Advisory Council on the Ethical Use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Data.

This council will be chaired by former Attorney-General V K Rajah and will work with the Infocomm Media Development Authority to address the ethical and legal issues arising from the usage of such technologies.

The council could not have come at a more timely moment, given the rapid developments in AI and Big Data in recent years.

AI is a set of technologies that can emulate human traits and processes including problem solving and even self-learning. Combined with data, such technologies can have wide applications.

Indeed, the unique interplay of AI and data will fundamentally affect how we live, work and play.

Take for example how it is possible for facial recognition technology, tapping on AI and data, to identify crime suspects at large-scale events, as seen in China.

This can be troubling from the privacy viewpoint.

On the other hand, there is a wide range of emerging AI and Big Data applications that businesses may exploit to derive new possibilities for their customers.

For instance, OCBC Bank has developed an AI-based automated chat system or “chat bot” called Emma that can communicate with customers and work out home loans - all without human intervention.

As part of the move to set up the new ethics council, the Personal Data Protection Commission (PDPC) has put up a discussion paper to outline how an AI and data governance model could look like.

PDPC is proposing an “accountability-based framework” where AI-aided decisions should be explainable, transparent and fair to consumers.

The bigger challenge for the new council is to look at the issue of “responsibility” from two very different angles.

First, responsibility may be cast to address questions in the broader sense of ethics and societal impact.

What are the permissible ways of using the AI and data and on what criteria are these based?

Are the considerations conceptual in the absolute sense of being right or wrong or are these contextual depending on the situations and circumstances?

What about the “shades-of-grey” argument where nothing is either right or wrong and everything is somewhere in between?

For example, if a social media company is privy to information that its customers may have committed some minor crimes, should it report to the authorities even if the law does not require so?

Second, beyond ethics, there is also the legal aspect of responsibility. Who is responsible if things go awry in AI applications and data use?

The classic case is when a driverless car gets into an accident. Is it the carmaker’s fault?

Or that of the computing hardware or software provider, mapmaker, car owner or even the government which builds the road?

COUNCIL MANDATES

With the broad range of issues involved, the council certainly has its work cut out for it.

So what should it not do?

First, it must not have mission creep and go towards mapping the directions for the technological development of AI or data.

This scope will be too formidable, and the efforts may will be an exercise in futility. We might actually even stifle new innovations through over-zealous guidance.

Second, while having many AI and data experts onboard may help, they may be more effectively tapped as resource persons.

In fact, not too many of them should be full members of the council so that its work is seen as neutral to specific technologies.

It will be fitting to have significant informed inputs from the vital stakeholders – people and organisations – who are the real user communities.

Third, ethics is a complex field within the broader discipline of philosophy.

Ethical reasoning is often associated with moral philosophy with its many schools of thought, some of which may be intimately intertwined with religious faiths.

Rigorous discourses are good and healthy. But we should not run the risk of “paralysis by analysis” and be drawn more on the debates and discussions than on the relevant or practical matters.

It is important that the council deliberations translate into actionable guidelines.

Fourth, it is understandable that the pressing issues may be more legal in nature. Having a strong legal perspective is a pre-requisite for the council.

The council should lay out the usage implications from the point of law along a broad policy perspective. But it should probably not comment on usage situations that may be too specific so as not to be seen as providing legal advice.

The crafting of a national code of ethics to guide AI and data use is a significant development for Singapore, and the Republic has the chance to be a trailblazer in this area.

At the moment, many of the existing codes tend to be done by technology vendors or professional bodies.

The United Kingdom has just articulated an intention to lead the world in having such a code while others like India and the European Union are also toying with the idea.

Mr Rajah’s council should not stop at just the code. Codes are not ends in themselves.

It will be even more crucial to foster strategies and plans for the continuing engagement of users of AI and data.

Practical suggestions may be offered via usage scenarios. The council’s work will be very dynamic and while we can codify the more basic precepts, it will be best to leave some aspects as guided case examples for reflection and learning.

These examples can be refreshed as and when needed in tandem with the changing technology development and policy thinking.

The setting up of the council is an affirmative step in the right direction. The intentions have been clear and purposefully stipulated.

The challenge now is to rightly scope its work, balance its composition and roll out a framework for engagement and practice.

It must address not just the use of AI and data in itself but more critically formulate processes to govern such use.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Lawrence Loh is director of Centre for Governance, Institutions and Organisations at NUS Business School, National University of Singapore. He is also deputy head and associate professor of Strategy and Policy at the school.