In Indonesia, identity politics is testing both democracy and diversity

April’s election will be the largest since Indonesia began the process of democratisation in 1998, with both the presidential and legislative polls being held at the same time across the country. What is at stake and why?

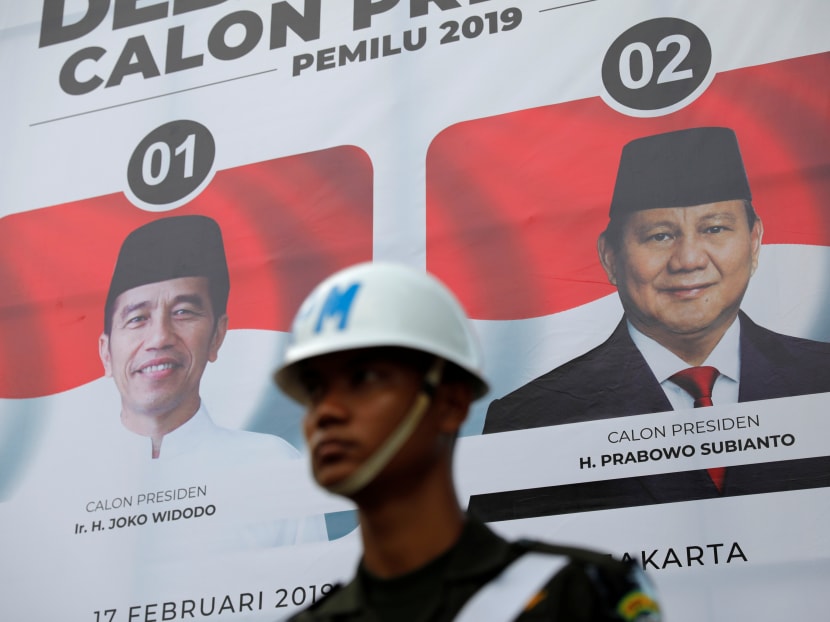

Indonesians will elect their next president in the country's upcoming election, choosing between the incumbent, President Joko Widodo, and ex-general Prabowo Subianto.

In two months, Indonesians will elect their next president, choosing between the incumbent, President Joko Widodo, and ex-general Prabowo Subianto.

This is a rerun of the 2014 election, when Mr Widodo, who quit his position as Jakarta’s governor, defeated the same rival by a 6 per cent margin.

In today’s Indonesia, with its complex democracy, diverse population and the world’s largest Muslim population, this is not a mere routine at five-year intervals. Larger issues loom over this political contest, which might determine the country’s future.

April’s election will be the largest since Indonesia began the process of democratisation in 1998, with both the presidential and legislative polls being held at the same time across the country. What is at stake and why?

First, the social solidarity of Indonesia’s over 250 million people – spread across more than 17,000 islands, with over 700 languages spoken by 300 ethnic groups – is under threat.

The country’s motto, “unity in diversity”, has not been easily maintained over its history. At least 500,000 people were killed in the traumatic anti-communist purge in the cold-war era, and many more as part of military efforts to curb secessionist movements in Aceh and Papua.

President Suharto’s authoritarian, militaristic rule entrenched centralised control for 32 years.

While the government is now decentralised down to the district level, with legislative and presidential elections being held on a one-person-one-vote basis, authoritarian rule has been replaced by horizontal tension and a complex power struggle between patrimonial political-business elites, who exploit the weak implementation of the law and resort to identity politics.

In both the 2014 and the current presidential election, the divisive issues of race, ethnicity and, most explosive of all, religion have been exploited to the fullest by campaigners. The effect of this strategy has been amplified by the use of hoaxes that have spread rapidly on social media.

The globalised post-truth climate, whereby emotional appeal trumps rational debate, clouds public perception and the ability of voters to soundly discuss issues.

This has not only created rifts within communities and families, but has also threatened national solidarity.

The persecution and trial on grounds of blasphemy of former Jakarta governor, Basuki Tjahaja Purnama, popularly called Ahok, a Christian of Chinese descent, showed how racial and religious sentiment, manipulated by the media, can gain the upper hand.

The trial centred on an edited video which went viral, in which Ahok mentioned a verse from the Quran during a campaign speech. The erasure of two words changed the meaning and tone of his statement, which angered conservative Muslims.

Although Indonesia’s Muslims are largely moderate and tolerant, there is a growing conservative trend among the educated, urban middle classes. The vision of an Islamic state, which was denied in the formation of the secular nation, is thriving, manifested in popular culture, people’s lifestyles and the sharia economy.

The 212 (December 2) street rally of Muslims in white garments demanding Ahok’s imprisonment in 2016 has since served as a symbol of defending the sharia aspiration. The banning of the radical Islamic group

Hizbut Tahrir Indonesia by the Widodo government, has strengthened the coalition of the conservative groups and the opposition leader.

This does not mean, however, that this is a battle between the secular and the conservative.

On the contrary, both Mr Widodo and Mr Subianto’s political ideology, if one can even call it that, is nationalist with a religious character.

Mr Widodo’s choice of an elderly Muslim scholar, Ma’ruf Amin, a key figure in the prosecution of Ahok, as his running mate, is a clear sign that no political power in Indonesia can avoid courting religion.

The fact that Mr Subianto himself comes from a cosmopolitan family, with a mixed Christian background and no strong bent towards Islamic piety, is not a contradiction, but an indication of the way the power game is played.

Meanwhile, his running mate, entrepreneur Sandiaga Uno, an American university graduate who was educated in a Catholic school, is represented as a devout, millennial “santri” (graduate of an Islamic school).

Apart from religion and race, the 2019 election has opened up a Pandora’s box of past traumas. The former son-in-law of Suharto, Mr Subianto brings with him an authoritarian, militaristic aura and the connections of the Suharto clan.

Moreover, communist phobia is pervasive at the moment.

While during the 2014 election, Mr Widodo had to clarify a fake obituary, which featured a photo of his younger self with a Chinese name, this time around, he has had to deny the rumour that he was a member of the banned Indonesian Communist Party.

In an election in which identity politics is a playing card and hoax a campaign strategy, not only social solidarity, but also the democratic foundation of the country itself is at stake.

In early January, a rumour spread on social media that seven containers from China were found in Tanjung Priok Port, containing cast ballots for Mr Widodo and Mr Amin.

This was clearly meant to cast doubt on the neutrality of the General Elections Commission, thus undermining the credibility of the election process itself. While the authorities moved quickly to squash the rumour, faith in the democratic model took a hit.

Given the economic standing and stability that Indonesia has achieved so far, and the demographic bonus of millennial youth looking forward to a vibrant future, April’s election will be a critical test.

If national solidarity and faith in democracy can be upheld, the country can look forward to fulfilling this dream. If not, then whoever wins the election will have to mend the shattered fabric that has held the diverse population together.

Indonesia is not alone in dealing with the global wave of right-wing populism, xenophobia and post-truth ignorance.

What Indonesian political elites should realise, however, is the cost of riding this dangerous wave for the future of the country. SOUTH CHINA MORNING POST

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Melani Budianta is a professor of literature and cultural studies at the Faculty of Humanities, Universitas Indonesia. She is an intellectual-activist, who has published works on gender and cultural diversity.