China’s place in world economy means novel coronavirus will hit global growth

Last week, I enjoyed a city break in Istanbul with my teenage daughter. It was made even better by the fact that we were upgraded to a €1,000 room for only €250 — in large part because our hotel, which expected to be booked solid by wealthy Chinese holidaymakers, was nearly empty.

Chinese citizens wear face masks to protect against the spread of the Coronavirus as they check in to their Air China flight to Beijing, at Los Angeles International Airport, California, on Feb 2, 2020.

Last week, I enjoyed a city break in Istanbul with my teenage daughter. It was made even better by the fact that we were upgraded to a €1,000 room for only €250 — in large part because our hotel, which expected to be booked solid by wealthy Chinese holidaymakers, was nearly empty.

Everywhere around the city, merchants displaying “Happy Chinese New Year” signs were even more aggressive than usual in hawking their wares to passing tourists. There weren’t many of us.

“It’s coronavirus,” said the concierge. “Last year around this time, we were packed. This year, nothing.”

We might be about to see something new: A global slowdown led by China, rather than the United States. The past four global recessions have been triggered by American consumers.

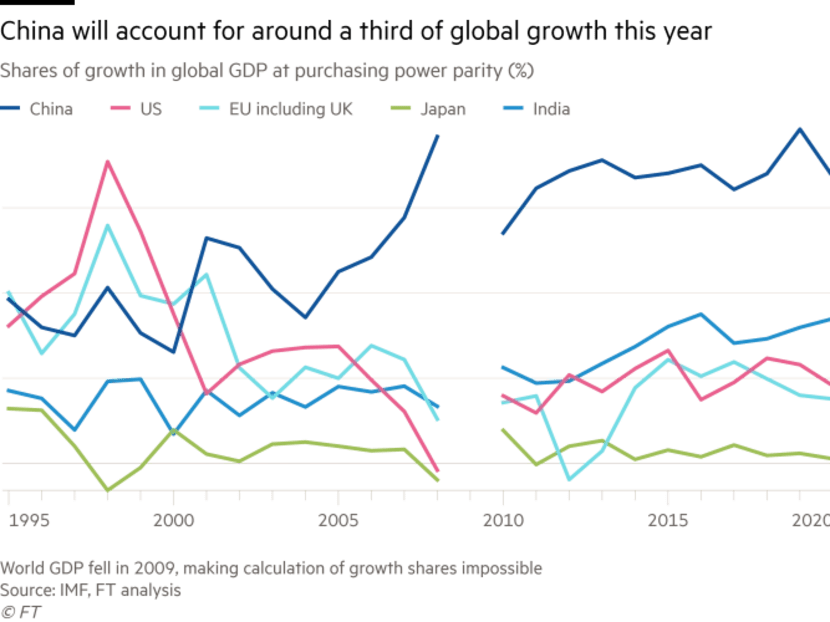

But China’s place in the global economy has grown dramatically over that time. China today accounts for about one-third of global growth, a larger share than the US, Europe and Japan combined.

While there is no doubt that growth has slowed in recent years, the base from which China is growing has exponentially increased.

As China bull Andy Rothman, an investment strategist with Matthews Asia, notes, while gross domestic product growth was at 9.4 per cent a decade ago, the base for last year’s 6.1 per cent growth was 188 per cent larger than 10 years ago.

It means that what Chinese consumers and workers do today matters a lot more than it once did.

“Chinese consumers drove global economic growth in 2019,” says Mr Rothman, just as they did for several years previously.

No wonder people in the hospitality, tourism, travel and retail industries are seriously worried about the impact of the novel coronavirus.

Chinese travellers are especially valuable because they tend to stay longer and spend more than those from other countries — in the US, for example, they stayed an average of 18 days and spent us$7,000 per visit last year, according to a 13D Global Strategy and Research report.

While Chinese spending in the US was already slowing because of the trade war, Asia and Europe will now feel its loss as well.

That will have knock-on effects in areas that are dependent on tourism: retail, restaurants, luxury goods and services of all kinds.

Goldman Sachs estimates a hit of 0.4 percentage points to China’s 2020 growth and a similar drag on US growth in the first quarter.

Optimists will note that during the Sars outbreak in 2003, Chinese growth dipped only briefly before rebounding to a robust 10 per cent.

But back then, China accounted for just 4 per cent of global growth, compared with 16 per cent today.

Consumer spending wasn’t nearly as developed, and Chinese tourism was still mainly inbound. “Consequently... the negative impact on global growth could be higher than in 2003,” noted an ING report on the topic.

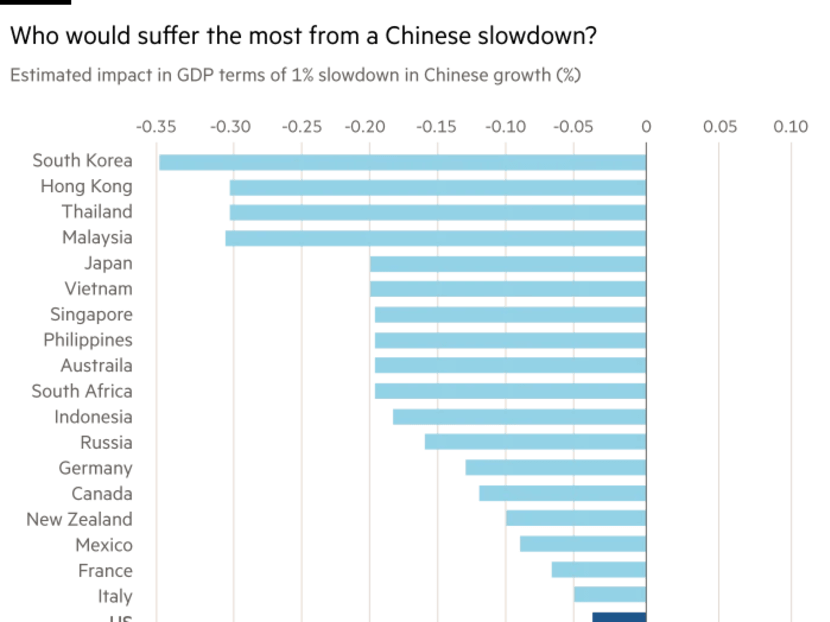

It is not only Chinese consumers who may drive a slowdown. The Hubei region is a huge area for supply chains.

Travel bans have made it difficult for people to work and to keep factories running. It is possible that with enough supply chain disruption China won’t be able to meet its US trade deal purchasing commitments.

That would of course have a geopolitical impact, particularly in sectors including technology, which are still among those most closely linked to Chinese businesses, despite the decoupling that is already taking place between the US and the Middle Kingdom (a trend that the “phase one” trade deal won’t change).

If the tech sector starts to look wobbly, that might affect energy and material inputs, and, in turn, be the catalyst for the larger market correction that many of us have been expecting for some time.

All this makes the outbreak of the virus exactly the sort of unexpected trigger event that many market participants have been fretting about — they are already worried about declining US corporate profit margins, record debt, liquidity issues and negative yields.

Of course, it is possible that the markets will shrug it all off for a while longer.

Perhaps US President Donald Trump will be able to claim, just in time for elections in November, that he was US president when the Dow reached 30,000.

But that potential market high would have been driven by monetary policy and deficit spending rather than any more productive White House strategy.

This underscores a wider point: whatever happens with coronavirus, the US has missed an opportunity, not just under Mr Trump but ever since the 2008 financial crisis, to reset its growth strategy, ideally to one based more on income growth than asset price inflation.

That is the only way to assure economic security over the longer term.

China, too, has been overly dependent on debt during the post-financial crisis period. It has brewed up its own bubbles in everything from real estate to provincial bonds.

Consumption and labour markets were weakening even before coronavirus hit. Trust in governance, already waning under President Xi Jinping, has taken a new hit with the party’s initial downplaying of the crisis.

And yet, whatever toll the virus may eventually take on global growth, the fact that recession fears, which seemed a non-issue only a week ago, are now back says something very important.

The US still matters a lot in the global economy, but much less than it used to. China, on the other hand, matters much more.

Just how much will be measured as the story of coronavirus plays out in the weeks and months ahead. FINANCIAL TIMES

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Rana Foroohar is Global Business Columnist and an Associate Editor at the Financial Times, based in New York. She is also CNN’s global economic analyst.