Protecting the retirement nest egg in the gig economy

Sixty-six years ago, the Central Provident Fund (CPF) Bill was raised in the Legislative Council in Singapore.

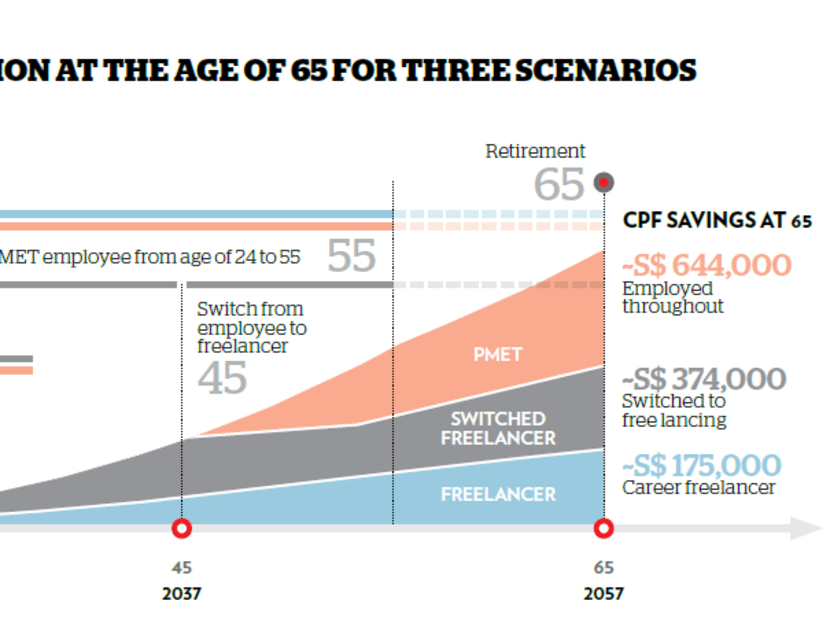

Key assumptions — Starting salary: S$2,856 (85% of S3,360, the median salary for university graduates in 2016); income growth rate: 2%; inflation rate: 2%; constant CPF interest rate as of today; no withdrawals between ages 55 and 64. Sources: CPF; MOM; Singstat; local and regional news; Asia Pacific Risk Centre analysis

Sixty-six years ago, the Central Provident Fund (CPF) Bill was raised in the Legislative Council in Singapore.

The motivation was straightforward, as the CPF Board website explains: “Many workers, except those working in the civil service or in some of the larger companies, were not provided with any form of retirement benefits by their employers. As a result, the workers had to depend on their personal savings when they retired, which was insufficient in most cases.”

When the Bill was passed into law five years later, the newspapers carried the optimistic headline “Now workers need not fear the day they have to retire”.

Fast forward to 2017 with the emergence of new economic realities, it is timely to re-examine whether the CPF, which has served Singapore well for more than 50 years, is still fit for purpose.

RISE OF THE GIG ECONOMY

Singapore has always had freelancers, or self-employed workers, who total about 200,000 in number. In contrast, “gig” workers — defined as independent workers utilising a technology platform to secure contract-based, short-term gigs — are a more recent phenomenon. The numbers are currently modest, with the Ministry of Manpower (MOM) estimating a total of 20,000 gig freelancers on online sharing platforms. However, these numbers are set to grow rapidly.

While there are no comparable data locally, analysis of American and European data suggests gig workers as a labour force segment are expanding 30 per cent a year.

Extrapolating to the Singapore context would mean 300,000 gig freelancers by the year 2030. Sound incredulous?

Consider that since ride-sharing platforms Uber and Grab entered Singapore just four years ago, the number of private-hire, chauffeur-driven cars has grown 70-fold from a negligible 500 to more than 40,000 today, or 1.5 times the number of taxis.

The appeal of the gig economy for workers is easy to understand — freedom, flexibility, being one’s own boss. These are stereotypical desires of millennials, important considerations in their joining the workforce. The gig economy also enables any Singaporean to supplement his income.

For businesses, the ability to engage contingent workers on-demand enables them to avoid the risk of being overstaffed, as well as the responsibility and costs of providing employee benefits, including mandatory CPF contributions. So what’s not to like?

The reality is that most of us live in and for the present and, like our forefathers before the advent of CPF, will neither set aside sufficient monies for retirement, nor medical insurance.

While gig freelancers are not entitled to other employment benefits, such as leave entitlement and family care, our focus is on retirement savings.

In Singapore, employers are currently required to contribute to employees’ CPF, up to a maximum of S$17,340 per year for residents.

However, as freelancers in the gig workforce are considered self-employed, they do not receive employer CPF contributions.

The exception is gig employees who are hired on contract, where employers are liable to pay CPF.

The CPF Board emphasises Medisave contributions and the attractive interest rates in encouraging the self-employed to top up their accounts.

Without strong motivation or incentive, many in the gig economy would likely limit voluntary contributions towards CPF outside of Medisave.

MANDATORY CONTRIBUTION?

The Marsh and McLennan’s Asia Pacific Risk Centre has modelled three worker archetypes: The first with traditional employment until age 65 years, the second starting a career with traditional employment but transitioning at age 45 years into the gig economy (“switched freelancer”), and the last gig freelancer embracing the gig economy right from day one.

The models are sobering and reveal the disparate fates of CPF balances across the three scenarios.

We can argue over the specific numbers, but the overall messages are indisputable.

First, gig freelancers are extremely vulnerable to retirement inadequacy, and even “switched freelancers” are at risk.

Second, CPF in an age of gigs needs a radical makeover.

Singapore is not alone. Other countries across the globe face similar challenges, and governments have started to examine ways to address the rights and social protection of gig freelancers. These offer Singapore myriad opportunities to learn from as we evolve our own solutions.

In Australia, the labour union in the state of New South Wales has recommended imposing minimum pay rates, and compensation insurance and pension fund contributions to be provided by the gig businesses.

Proposals in America have included Individual Security Accounts, which are envisaged to be universal, portable and attached to workers rather than employers.

How do these work? The employer pays a set amount for each worker, pro-rated to the number of hours the employee works for that employer, into a fund that forms the worker’s personal safety net at an individual level.

This is not a new idea, and has been deployed in mining and construction. Will this raise costs of gig freelancers and hence for customers? Will this mean less money in the wallet for gig freelancers? The answers to both questions are “yes”.

But it could be argued that the absence of a safety net benefits the companies and the gig freelancers “until the day that it doesn’t”, as United States Senator Mark Warner wrote in The Washington Post. “That’s also the day that taxpayers could be handed the bill,” he added.

Hence governments have a right and duty to intervene early and establish systems that protect gig freelancers and taxpayers.

The Singapore Government has sensibly not rushed into specific proposals, but instead highlighted its concerns and called for national discussions.

Ongoing surveys by MOM will include gig freelancers.

In Parliament earlier this year, Manpower Minister Lim Swee Say announced the formation of a “tripartite workgroup to study these issues, address the concerns of the freelancers, and come up with workable solutions for the well-being of the freelancing workforce in our future economy”.

The CPF would certainly be a central part of these discussions. While it is too early to assert with any finality, some form of mandatory contribution to provide for retirement security is appropriate.

Our view is that the CPF should be the default vehicle, given its established track record, familiarity to Singaporeans and structures already in place for contributions collection, investment, and disbursement.

This also presents opportunities for other organisations to have a participating role. The National Trades Union Congress has formed the Freelancers and Self-employed Unit, which currently offers group insurance coverage to its members, and could be an avenue to help members manage and access retirement funds.

In the US, private companies such as MBO Partners assist independent contractors to establish solo tax-qualified, defined-contribution pension accounts legally termed 401(k) plans.

The CPF Board’s logo is widely known to all Singaporeans, but what is probably less noted is the rich symbolism behind it.

The circle represents “completeness of the CPF system as a national social security savings scheme”, the three keys, Government, employers and employees, and finally the colour green highlighting the need for constant growth and dynamism. We are sailing into uncharted waters as a country and as an economy; may the CPF evolve to continue to meet the needs of Singaporeans and serve us well into our retirement years.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS:

Dr Jonathan Tan is a director in Marsh and McLennan Companies’ Asia Pacific Risk Centre, which focuses on analysing key risks facing industries and societies in Asia. Dr Jeremy Lim is a partner in the Oliver Wyman Singapore office focusing on health and social issues. The findings cited in this commentary were presented at the Singapore launch of the World Economic Forum Global Risk Report 2017.