In these uncertain times, hope is a strategy

In a media interview on March 12, Dr Michael Ryan, the World Health Organization’s Head of Emergencies, called on governments to respond aggressively and systematically to the Covid-19 pandemic. He added pithily: “Hope is not a strategy.” But the more I thought about it, the more I wondered, why shouldn’t hope be strategy?

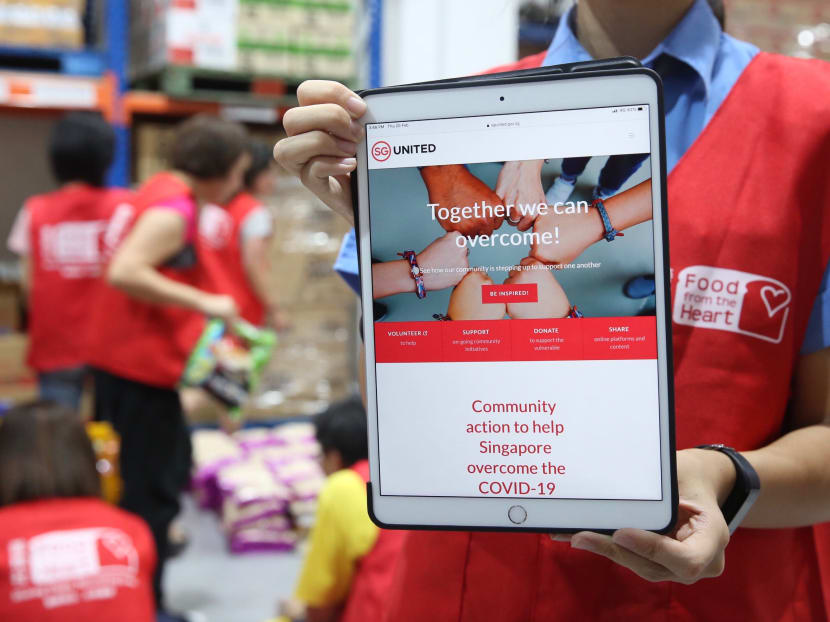

A volunteer holding up a tablet during the Feb 20 2020 launch of SG United Portal for Singaporeans looking for an avenue to contribute to the national response to Covid-19.

In a media interview on March 12, Dr Michael Ryan, the World Health Organization’s Head of Emergencies, called on governments to respond aggressively and systematically to the Covid-19 pandemic. He added pithily: “Hope is not a strategy.”

And there it was. He said what had been on the minds of many of us who work in strategy and scenario planning. I found myself agreeing heartily with Dr Ryan, because “hope is not a strategy” is one of my favourite aphorisms, which I use in conjunction with “and luck is not a method”.

Plus, Dr Ryan made that remark having praised Singapore for its coherent and systematic approach to dealing with Covid-19.

In this current state of crisis, clearly some states have been plunged into crisis, while others have distinguished themselves as "crisis states" par excellence: Systematic, well-organised, hyper-sensitive to risks, leaving nothing to chance. Or hope.

But the more I thought about it, the more I wondered, why shouldn’t hope be a strategy?

If you go by the standard definition of “strategy”, say by British war studies professor Lawrence Freedman in his tome “Strategy: A History”, it is a balance between ends, ways, and means.

Without an articulation of ends — desired or hoped for outcomes — the combination of ways and means simply produces busy-ness.

Of course, one might add that ends and ways (tactics and methods) without means (resources needed to achieve the goals) is fantasy, and ends and means without ways is cleaving to luck as method.

All three elements should be there, albeit in different proportions.

So clearly hope is an integral part of strategy, and indeed of the human condition. But there are many ways to define hope, and many ways to hope. In these uncertain times of Covid-19, here in Singapore and across the world, perhaps it behoves us to reflect on the question of hope.

For example, hope can be seen in ontological terms as an emotion or disposition, even as an existential stance.

Or hope can be seen more in behavioural terms, directed towards a more or less well-specified end. It finds expression in sentences such as “I hope that X” or “I hope for X”.

The former is abstract and open-ended — “I am hopeful” — whereas the latter is focused, concrete and more than a little pragmatic.

In Singapore, where pragmatism comes closest to being a national creed, hope tends to manifest not only in a goal-directed manner, but paradoxically, hope is carefully restrained.

Of course, there have been some mavericks among us — both past and present, in government and outside of it — but by and large, societally we tend to keep hope “real”. It is the rare person who is hopelessly hopeful. After all, our defining national trait is kiasu-ism.

Indeed, this careful and practical way in which we hope has stood us in very good stead in dealing with crises in the past, of which Covid-19 is merely the latest.

We do hope in a dispassionate and objectively-calculating sort of way, with a probability forecast attached to it, whether explicitly or not.

Ever mindful of false hope, our approach to hope is tempered and fastidiously calibrated by a keen awareness of resource constraints and other limitations.

This is serving us well in the current pandemic, as it has over past crises.

However, by carefully studying how things are, in order to extrapolate how things might be, hopes in this vein are rarely transformative. In fact, by adhering so closely to reality, hope tends to reproduce this reality rather than to transform it.

We take too far British literary theorist Terry Eagleton’s distinction between hope and optimism. Professor Eagleton is scathing in his criticism of optimists in this excerpt from “Hope without Optimism”:

“There may be many good reasons for believing that a situation will turn out well, but to expect that it will do so because you are an optimist is not one of them…If there is no good reason why things should work out satisfactorily, there is no good reason why they should not turn out badly either, so that the optimist’s belief is baseless.”

He goes on to encourage us to have “authentic hope” instead that is “underpinned by reasons”.

“It must be able to pick out the features of a situation that render it credible. Otherwise it is just a gut feeling…Hope must be fallible, as temperamental cheerfulness is not.”

We must certainly avoid the shallow and banal optimism that prevents us from acknowledging stark and hard truths of our situation. But while I agree that we must have reasons to and for hope, and that hope must be fallible, an extreme pragmatism renders it cheerless.

Sometimes hope needs to be a bit reckless and restless. There is something to be said for hoping against hope.

Because we are emotional beings, if we simply formed our strategies on the basis of objective analysis and evidence-based calculations, we would collapse in a heap of anomie under the onslaught of apparently incontrovertible facts and the admonishment to be realistic.

Hope therefore must be the quality that enables us, as individuals and as a collective, to overcome the burden of evidence and to shake off the shackles of predetermined elements in our environment.

So not to denigrate the virtues of the crisis state, and certainly not in the midst of Covid-19, but if hope only ever manifests as a survivalist response to trauma, then it fails in its bigger role of giving meaning to human existence.

And while to thrive in life necessarily requires that you first survive its trials and tribulations, mere survival is not the whole point of life. So a crisis state, if it can do nothing else other than solve crises, itself constitutes an existential crisis.

As American philosopher Richard Rorty put it in “Achieving Our Country”, hope is “taking the world by the throat and insisting that there is more to this life than we have ever imagined”.

Hope, ultimately, has to be hopeful, even if at times it is hopelessly so.

As it turns out, hope is an integral part of strategy after all. Sometimes the problem is not that hope is a strategy, but that it is not.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Dr Adrian W J Kuah is Director of the Futures Office, National University of Singapore. This is his personal comment.