What the Anglophone reaction to the Pisa test results tells us

The results of the 2015 Programme for International Student Assessment (Pisa) test were released about a week ago, and the usual media hype has followed.

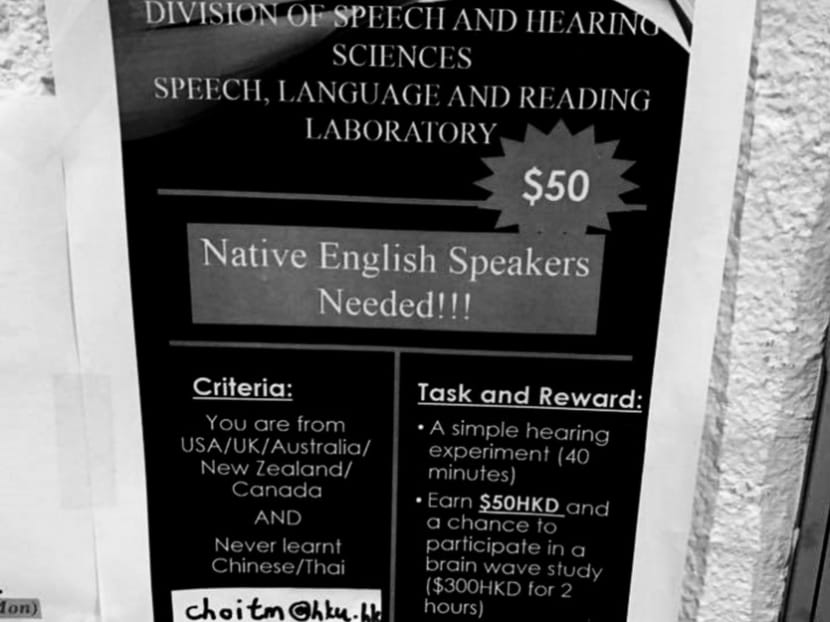

A university ad in which associations between ‘native English speakers’ and particular nationalities were made. Photo: Luke Lu

The results of the 2015 Programme for International Student Assessment (Pisa) test were released about a week ago, and the usual media hype has followed.

A litany of analyses has been written and the conventional narrative is about how the East Asian nations are top again in Maths and Science. The somewhat predictable discussion is often framed around the purpose of such testing, as well as whether the Western world ought to be emulating practices that have worked so well for students in Hong Kong, Japan, South Korea and Singapore.

What is never mentioned is this: Singapore is ranked top in Reading, in English, the medium of instruction in all its schools. It outperformed Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom and any other nation with “native speakers” of English. Nor is this the first time this has happened.

Singapore ranked fifth in 2009 and third in 2012 for Reading, the highest-placed country where English is the medium of instruction.

So why has the dominant narrative always been what the West might learn about teaching Maths and Science from East Asia? Why have commentators in the Anglo-world not written about looking to Singapore as a model for teaching English?

The answer, I believe, lies in how most people and nation states in the world today continue to link biological heritage and phenotype with cultural and linguistic practice.

That is, one’s proficiency in and supposed affiliation to a language is tied up with one’s race, ethnicity or nationality. This idea is translated into racialised (even racist) discourses in our daily interactions, the advertisements we see, government policies and even interpretations of Pisa test scores.

In 1998, sociolinguist Thiru Kandiah wrote a politically-charged piece regarding the hierarchical status amongst English-users in the world.

He gives the example of an advertisement published in The Straits Times. On July 12, the advertisement read: “Established private school urgently requires native speaking expatriate English teachers for foreign students.”

On July 14, the same advertisement had been altered: “Established private school urgently requires native speaking Caucasian English teachers for foreign students.”

To Prof Kandiah, such discourse immediately pointed to the marginalisation of “an upstart bunch of English users across the world, who had been taught the language so well by their ‘native speaking’ teachers that they now entertained the delusion that they were reliable and valid users, interpreters and judges of the language”.

Things have not changed much since 1998. A friend recently shared an advertisement in a Hong Kong university, where the same associations between “native speaker of English” and particular nationalities were made.

In the UK, its Border Agency stipulates that all international students applying for visas must provide academic proof of proficiency in English, unless one is a national of countries such as Canada, Australia, New Zealand and Ireland.

These examples all show that racialised discourses regarding the status of so-called “native/non-native speakers of English” are very much alive and prevalent today.

In other words, even if Singapore is ranked best in the world for reading English, such discourses suggest that we will still not be considered “reliable and valid users” able to judge, evaluate or take ownership of how English ought to be spoken/written.

The Anglophone silence regarding Singapore’s proficiency in English might be attributed to plain ignorance (not knowing Singapore’s education system) or racism (unable to accept that Asians might have anything to offer about teaching the language).

Both stem from essentialist and ethnocentric attitudes. People from East Asia and who look Asian are assumed not to speak or write English well. Stranger still if they should claim English as their mother tongue.

I have lost count of the number of times I have been complimented on my “accentless” and good English while living in the UK and travelling in Europe.

As long as these attitudes persist, the global status of Singaporean or any “non-native” English-speakers will never change.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Luke Lu is a Singaporean PhD candidate at the Centre for Language, Discourse and Communication, King’s College London. He taught General Paper in a Singapore junior college for four years.