Commentary: What indigenous people and naturalists taught me about the planet's health

As a young adult who has lived in bustling Singapore all her life, I am often surrounded by towering skyscrapers, concrete walls and constant traffic, with few opportunities to be immersed in nature.

As a young adult who has lived in bustling Singapore all her life, I am often surrounded by towering skyscrapers, concrete walls and constant traffic, with few opportunities to be immersed in nature.

Perhaps for this reason, I have always been drawn to people who work and live closely in the natural world, such as members of indigenous tribes as well as naturalists.

I remember being completely obsessed with my O-Level English literature novel, Whale Rider, written by Witi Ihimaera.

The book described how the Maori people, who were indigenous to New Zealand, shared a tight bond with whales which they sought to protect and believe were important to the survival of their tribe.

I often wondered at that time, about 12 years ago, would there still be people like the Maoris in the future? Would they still care about their culture and environment?

Recently, I had the rare opportunity to meet people hailing from indigenous tribes, as well as scientists who work in natural landscapes such as caves and rainforests.

It started in the last week of May, when I flew to Bangkok for an international exchange seminar on public health and climate change.

I went in the capacity of a young doctor with an interest in public health, with my head filled with statistics related to climate change and its implications for human health, such as dengue fever, heat stroke and mental illnesses.

However, I was admittedly less familiar with the narratives of biodiversity and climate change and have not yet interacted much with those with an ardent passion for environmental protection.

While on my way to Bangkok, my social media pages were flooded with quotes like:

"The earth does not belong to man, man belongs to the earth...

Man did not weave the web of life, he is merely a strand in it.

Whatever he does to the web, he does to himself."

This native American quote, along with other wise sayings by environmentalists and climate change activists were posted and shared online in the lead up to World Environment Day on June 5, increasing my anticipation of what lay ahead of me.

Several seminar delegates I met at the conference were particularly memorable.

One of them was a vivacious woman from the Mekeo tribe of Papua New Guinea named Yolarnie Amepou.

I remember seeing her donning a loose dress with prints of Sepik carving, Tolai mask and Tabu shell money that reminded everyone around her of her unique identity and heritage.

As an environmental advocate who led conservation efforts over pig-nosed turtles, dolphins, sharks and rays, she believes that educating the young about biodiversity would inform them of their responsibility to sustainable management and protection of the environment not only for themselves, but for the world as well.

She is not the only one with such aspirations.

Throughout the conference, I heard of the lengthy efforts made by indigenous people to conserve species of wildlife or to reclaim their native lands.

Many did so to retain their cultural and natural resources, and also with the aim of reducing global warming so as to safeguard their community’s access to clean air, potable water, ample food and shelter.

Their firm voices and moving stories gave me a refreshing perspective of how nature and culture are intrinsically linked to the longevity of mankind, and put a human narrative to the cause of planetary health beyond the stats and data that I was so accustomed to.

The other fascinating delegate was an Assistant Professor at the University of North Carolina Charlotte named Laurel Yohe, who often travels to South America and Southeast Asian countries such as Vietnam to study bats.

As a passionate bat biologist, Laurel wore her striking necklace with a bat pendant everywhere she went and shared about her expeditions in the dark where she captured, released and continued to monitor bats which were measured, clipped and released.

She also spoke of how her research studied nasal systems in bats as she tried to understand how bats can survive with lethal pathogens that are otherwise harmful and even deadly to humans.

Her work became all the more relevant with the emergence of Covid-19, as bats and other closely related mammals are known reservoirs of coronaviruses.

As she spoke about bats with zest, I was often reminded about the possible surfacing of new zoonotic diseases, the importance of preventive approaches to these diseases as well as how the study of these animals may lead to potential treatments.

The health of humans is dependent on the state of the Earth’s natural systems, and we have only one Earth.

Planetary health is a complex, multidisciplinary and emerging field that will undoubtedly be of paramount importance.

This seminar has made me think more deeply about what we should do to reduce environmental devastation in our own capacities, as well as communicate this beautiful idea to the public in a more convincing and appealing way.

It also allowed me to make the serendipitous discovery that my interest lies in preventive medicine, which encompasses occupational medicine and public health.

In the future, I hope to have the opportunity to learn more about how environments, occupations, climates and other risk factors affect diseases like communicable and non-communicable diseases, and find out ways to prevent such conditions.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

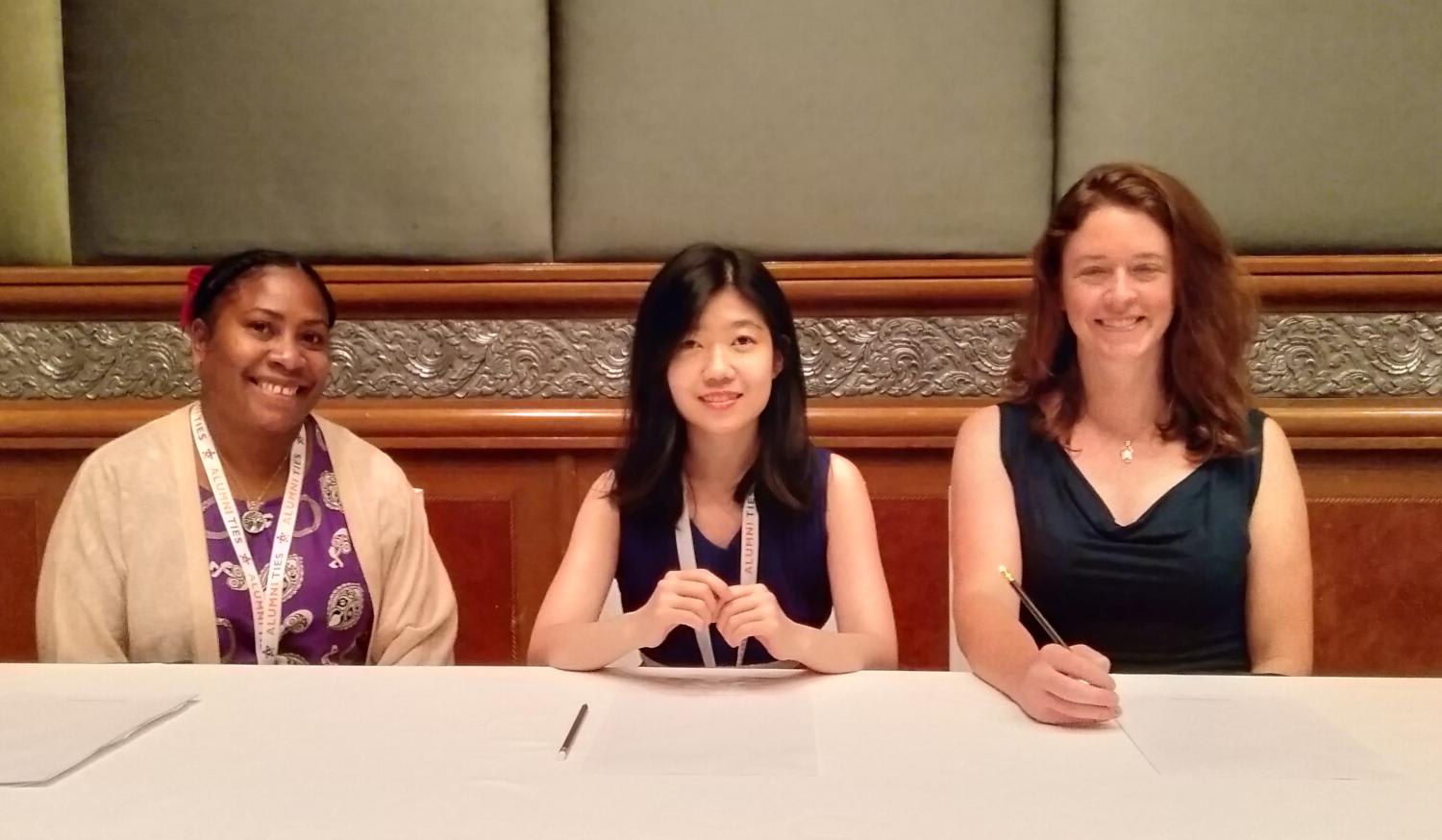

Alvona Loh Zi Hui is a junior doctor at a public hospital in Singapore and a delegate of Alumni Thematic International Exchange Seminars 2022 in Bangkok organised by the US State Department.