A year into the pandemic, Asean copes — and hopes

Covid-19 started as a slow burning shock to Southeast Asia about a year ago. Some countries, bolstered by past experiences of Sars and H1N1, sprang into action and were successful in their containment measures, at least initially. Others were slow and even in denial about the entry of the virus into their borders at first, but the disease soon proved itself a virulent scourge that could not be wished away.

Despite the long shadow cast by the pandemic, 60.7 per cent of Southeast Asian observers approve of their own government’s handling of the crisis.

Covid-19 started as a slow burning shock to Southeast Asia about a year ago. Some countries, bolstered by past experiences of Sars and H1N1, sprang into action and were successful in their containment measures, at least initially. Others were slow and even in denial about the entry of the virus into their borders at first, but the disease soon proved itself a virulent scourge that could not be wished away.

A balancing game between lockdowns to minimise casualties and avoiding a paralysing seizure of economic activities has ensued, amid fresh outbreaks over the last few months.

As the anniversary of the virus’ appearance arrives, Iseas-Yusof Ishak Institute's State of Southeast Asia 2021 survey of 1,032 academics, policymakers, business people, civil society leaders, the media as well as regional and international organisations shows that there is no complacency about the pandemic in the region.

Covid-19 registered strongly in the minds of opinion makers in all 10 Asean countries as a top challenge. More than 60 per cent of respondents highlighted its health impact and more than 50 per cent its economic impact.

Despite the long shadow cast by the pandemic, 60.7 per cent of Southeast Asian observers approve of their own government’s handling of the crisis.

When we drill down into country-level responses, there is considerable diversity as one would expect given the differing ground situations.

Less than half of respondents in Indonesia, the Philippines, Myanmar and Thailand strongly approve or approve of their government’s response, while the same category for Malaysia and Laos hovers around 55 per cent.

Three countries (Singapore, Vietnam and Brunei) with positive responses above 90 per cent pulled the regional average approval rating up while that in Cambodia constituted a robust 80.7 per cent.

At the time of the survey (between Nov 18 last year and Jan 10 this year), the disease in Indonesia and Philippines was very serious by regional standards and even the latest strategy of relying on vaccinations was running into supply and logistics challenges.

The situations in Myanmar and Thailand were less dire, but fresh outbreaks in both countries had clouded the prognosis there.

The picture in both nations has been further compounded at the time of writing by political protests and demonstrations that may complicate management of pandemic risks.

In general, survey respondents who approve of their government’s response do so because they had carried out adequate public health measures to mitigate the disease.

Overall, almost 85 per cent of them cited this reason for their approval. The other measures that a significant number of respondents believe were well done were the provision of financial relief measures and consultation with medical and scientific professionals.

Financial relief measures were seen to be good in five countries (Myanmar, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore and Philippines) while it was not much of a factor in four (Laos, Thailand, Brunei and Vietnam).

The contributions of doctors and scientists on the other hand were most appreciated in Thailand, the Philippines and Brunei.

Some countries had a significant number disapproving of their government’s response measures.

Filipinos, Laotians and Indonesians wished for more medical and scientific input into their government’s response.

Thais and Myanmars wanted more financial relief, even though other respondents from the latter country thought this was a good part of their government’s response.

Malaysians who disapproved of their government’s response were alone in voting most strongly for their politicians and public servants to show a better example in observing public health measures instead of flouting them.

This is not surprising given the number of high-profile cases of such errant behaviour widely reported by the Malaysian press.

On the response of Asean as a regional grouping, the inability to overcome the Covid-19 pandemic featured as a top concern for just over half of the survey respondents.

The feeling in past surveys that the impact of Asean’s work could not be felt on the ground has given way this year to concerns that Asean lacks the capabilities to deal with issues where it matters most, Covid-19 being one such issue.

Indonesians were alone in picking this as Asean’s biggest concern while Laos and Myanmar had it as their second highest concern.

For the other seven countries, the need for Asean to manage geo-political issues such as fluid political and economic developments, and major power competition were bigger worries than the pandemic.

Respondents also were asked “which Asean country has provided the best leadership to Asean on Covid-19?”

A plurality of respondents were of the view that Singapore (with 32.7 per cent) and Vietnam (with 31.1 per cent) provided the best leadership to the grouping The next highest choice by 18 per cent of the respondents was to abstain.

At the country-level, respondents from eight countries felt that Singapore provided the best leadership, while Brunei and Vietnam picked Vietnam.

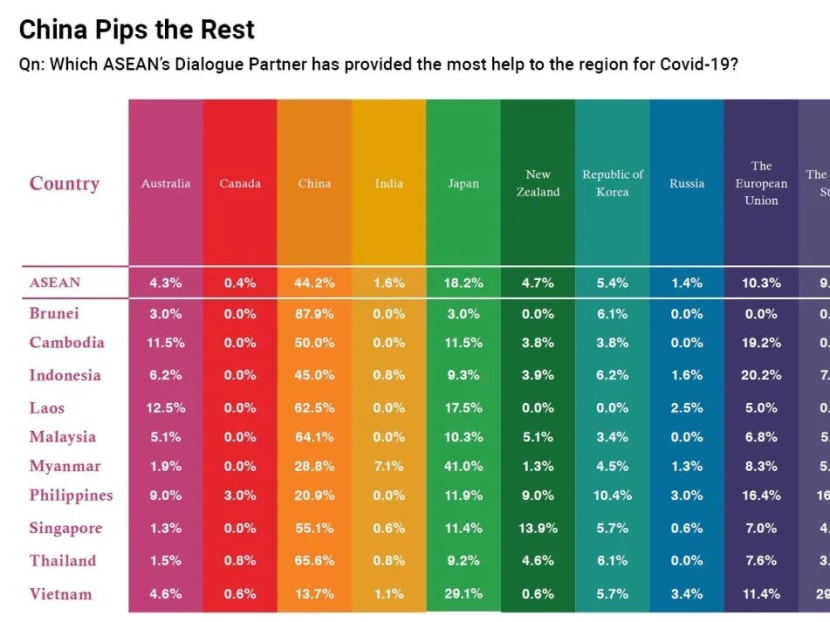

Among Asean Dialogue Partners, China stood out clearly with 44.2 per cent of votes as the country that “provided the most help to the region for Covid-19”.

This is not surprising as China engaged Asean states early in the pandemic and was forthcoming with practical help in the form of personal protective equipment and later vaccines.

The next highest picks were Japan with 18.2 per cent, the European Union with 10.3 per cent and the United States with 9.6 per cent.

Notwithstanding this clear recognition that Chinese diplomacy was the most substantive and timely, other results in the survey showed that the distrust in China as a strategic partner has edged up in this survey compared to that in 2020.

The reasons are however more linked to non-Covid issues such as the growing perception of China as a revisionist power and its behaviour in the South China Sea.

Continued carry through of Covid diplomacy by China should still help strengthen its account in the region, especially if it is accompanied by assurances in those other areas as well.

Even though Southeast Asia has not done too badly overall, Covid-19 has undoubtedly been a wake-up call for everyone.

While this pandemic will pass in time, the need to be more ready for the next outbreak is clear.

If there is one lesson that needs to be well learnt from the past year, it is that future outbreaks are not a matter of “if”, but “when”.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Choi Shing Kwok is director of Iseas–Yusof Ishak Institute and head of the Asean Studies Centre at the institute. This piece first appeared on the institute’s Fulcrum website which analyses developments and trends in Southeast Asia.