The ‘butterfly’ boy

SINGAPORE — Most children go wild at playgrounds, running and jostling for the slides and swings. For nine-year-old Harshit Talwar, however, playtime only starts after everyone at the playground has gone home. In school, he sits in a corner while his friends play ball games during recess and PE.

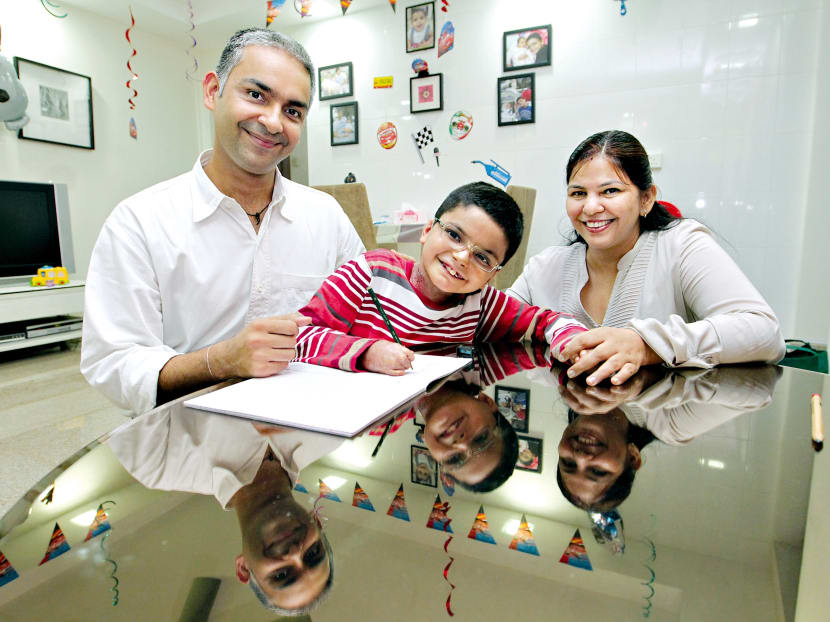

Despite the pain and surgery that he has undergone, Harshit (centre) is a cheerful boy, said his father and mother. Photo: Koh Mui Fong

SINGAPORE — Most children go wild at playgrounds, running and jostling for the slides and swings. For nine-year-old Harshit Talwar, however, playtime only starts after everyone at the playground has gone home. In school, he sits in a corner while his friends play ball games during recess and PE.

The articulate primary-schooler shared that he often feels lonely. “Sometimes I feel like crying inside when I see my friends having fun,” he said.

Yet, keeping Harshit away from the rough and tumble of childhood is necessary for his health. He is born with epidermolysis bullosa (EB), an inherited, painful skin disorder that causes the skin to tear and blister at the slightest trauma.

The genetic disorder affects eight out of one million births worldwide. In Singapore, about 30 to 40 families have children with EB, who are also known as butterfly children because their skin is as fragile and tear as easily as butterfly wings.

About 10 to 15 children, including Harshit, are on follow-up care at KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital’s Dermatology Service.

UNKNOWN GENETIC CARRIERS

Both Harshit’s parents are “carriers” of the recessive EB gene, but they were not aware of it until he was born with blisters behind his ears and on the legs. Harshit has a younger one-year-old sister, who has not inherited the disease.

The skin is made up of the outer layer (known as the epidermis) and inner layer (the dermis). In healthy skin, proteins hold the two layers together. However, genetic mutations in children with EB leads to decreased or abnormal skin protein, said Dr Mark Koh, head and consultant at KKH’s dermatology service.

Any movement can create friction between the layers, causing blisters. The most serious forms grapple with severe skin blistering, ulceration and scarring throughout their lives, as in Harshit’s case.

“This can be very painful and may even lead to the amputation of the fingers or toes. Skin cancer can occur in early adulthood or adulthood in some of these patients. Very severe forms of EB can result in death from infections during infancy or childhood,” said Dr Koh.

NO KNOWN CURE

Despite ongoing research on the treatment of the condition, there is currently no known cure or prevention for EB.

“Prenatal genetic testing can be performed for families who have a known mutation. This is usually done in the first trimester of pregnancy to help better prepare the parents to manage the child’s condition,” said Dr Koh.

In recent years, the use of bone marrow transplant to treat EB has been attempted in some hospitals, mainly in the US. However the procedure is associated with very severe complications, including infections, added Dr Koh.

For now, all Harshit’s parents can do is to manage the symptoms and keep him safe from potential injuries.

A SCRAPE COULD BE CATASTROPHIC

This is important as an accidental bump, minor tumble or scrape could cause Harshit’s skin to blister or “peel off like an onion, exposing the raw layer underneath”, said his father Navdeep Talwar, 37, a software engineer.

“Every time that happens, it is very painful for Harshit and it means that he will have to miss at least five days of school in order to recover. There was once he missed 15 days of school because of a fall,” said Mr Talwar.

The repeated excessive scarring has also caused Harshit’s fingers to fuse together. He has no nails on his fingers and toes. While the tenacious boy is able to make do with his thumb and index finger to hold a pencil and write, he is unable to do more complex tasks.

He needs help to use an eraser, sharpen his pencil, pick up or open his school bag, and bathe. His mother had to quit her job at an events management firm when he was born. Together with their helper, she take turns to carry his school bag in between classes.

Because of his condition, Harshit’s body has been wrapped in bandages since birth. Bath times are especially excruciating for him as that involves a long, tedious process of removing the bandages, said Mr Talwar.

MORE SURGERY AHEAD

Having spent S$50,000 to S$70,000 on his son’s medical condition since he was born, Mr Talwar, who is currently the sole breadwinner of his family, is trying to save up money for Harshit to undergo surgery to separate his fused fingers.

“Harshit took months to recover from the previous surgery and it was torturous for him. Now his fingers have fused together again. The doctor recommends more surgery but we want to wait until he is 13 or 14 years old. He can at least understand more and bear with the pain better,” said Mr Talwar.

He added: “Despite all that he has gone through, Harshit is a cheerful boy. If you look at his face, you won’t think he has any problem.”

Looking forward, the Talwars are hoping for an EB cure and a stab at normal life for their son. Harshit however, has bigger dreams for himself. “I would love to be an astronaut and explore space. That would be great fun. There is nothing left in life without fun,” he said.