Saving lives with vinegar

In Singapore, we are used to medical care being high-tech. But “low-tech” does not mean inferior — not when the innovative use of household items is helping to save women’s lives in Indonesia.

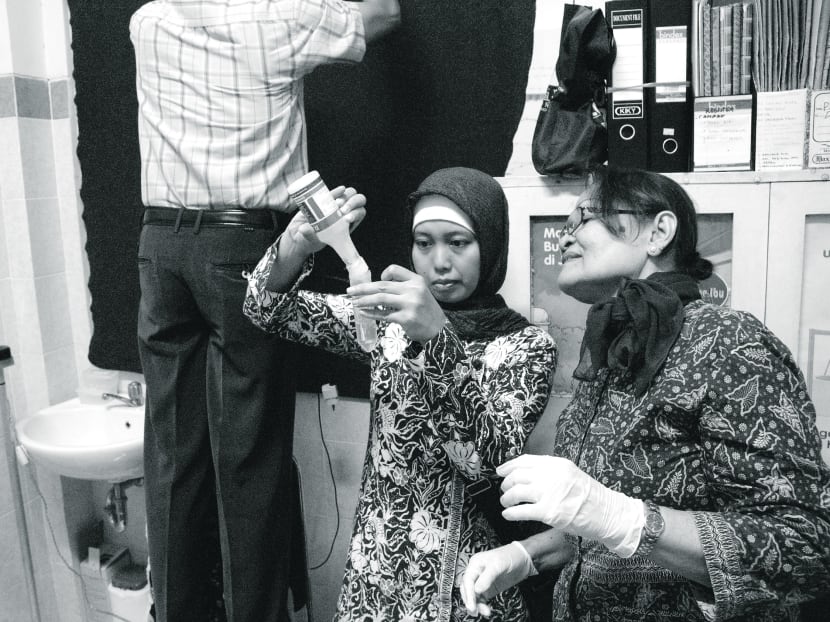

In Puskesmas Kelurahan Malaka Jaya, a village-level primary health centre in Jakarta, the workstation of senior midwife Tiurma Sianturi consists of home-made cotton swabs, diluted cooking vinegar, a lamp and a bed. With these, she performs cervical cancer screening for the village wives.

The procedure is simple, no doctors required: Ms Tiurma swabs vinegar onto the cervix and within a minute, any pre-cancerous spots will turn white and can be spotted with the naked eye.

Lesions can then be removed on the spot with a metal probe cooled by a tank of carbon dioxide (cryotherapy), or advanced case patients may be referred for a biopsy or colposcopy.

This method combining Visual Inspection with Acetic Acid (VIA) and cryotherapy was pioneered over 20 years ago simultaneously by Dr Paul Blumenthal, a Johns Hopkins gynaecologist working in Africa, and Dr Rengaswamy Sankaranarayanan in India. It has gained international attention and, in 2010, was endorsed by the World Health Organisation.

In June this year, at the American Society of Clinical Oncology meeting in Chicago, researchers reported the impressive results of a 15-year study of VIA in India.

“We had a 31-per-cent reduction in cervical cancer deaths. That was very significant,” said Dr Surendra Shastri of the Tata Memorial Hospital, one of the study’s authors.

PAP SMEARS OUT OF REACH

But why all this buzz about another method of screening, when the Pap smear was introduced to the world almost 100 years ago?

The Pap smear has made cervical cancer a preventable disease as it enables the detection of pre-cancerous lesions. Thanks to mass screening programmes, the number of cases and deaths has plummeted by 70 to 80 per cent in developed countries.

However, in other places such as Indonesia, cervical cancer remains a scourge: Over 85 per cent of the cases globally occur in developing countries. In Singapore, cervical cancer ranks No 9 among cancers diagnosed in women — but in Indonesia, it is the most common cancer overall. Every hour, one Indonesian woman dies as a result of cervical cancer — an unacceptable statistic for a disease that can be prevented.

A Pap smear screening programme is expensive, requiring costly equipment, laboratory infrastructure and trained personnel. Indonesia has only 292 pathologists to serve nearly a quarter of a billion people; little wonder that only 5 per cent of women underwent any cervical screening, according to a 2004 study.

A second harsh fact of reality is that many women in Indonesia are not even aware of cervical cancer. Social stigma, fear and reluctance to travel to hospitals for diagnosis and treatment has meant that 70 per cent come to the hospital too late, presenting advanced disease by then.

CAN-DO ATTITUDE

In 2004, the “See & Treat” programme — so named because screening and treatment are done in the same visit — was introduced by the Netherlands-based Female Cancer Foundation with the support of the Indonesian Ministry of Health.

It is now in more than 15 provinces, and more than 224,500 women aged 25 to 50 have been screened.

There was immense effort invested in socialising and educating the community, recalls Dr Laila Nuranna, coordinator of the Female Cancer Programme in Jakarta. Members of the Family Welfare Women Organisation serve as health cadres, reaching out to educate women and their husbands about cervical cancer.

Husbands are critical partners — both for the initial encouragement to come forward for screening, and in consenting to cryotherapy to remove pre-cancerous spots (after treatment, women are counselled to abstain from sexual intercourse for a month, and Indonesian cultural norms often require wives to ask their husbands for permission for the treatment).

While Dr Laila knows more needs to be done, they have a committed team, a sense of mission, and a working model which is grounded in good science and tailored to local sensitivities. There is much we can learn from their experiences.

Working within low-resource constraints, healthcare providers like them are compelled to innovate and seek practical solutions that we in well-equipped Singapore may never even have considered. But more important than the solutions are the can-do attitude, inventiveness and community spirit that serve as an example for any setting — rich or poor, large or small.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS:

Fatimah Z Alsagoff is from the Secretariat of the ASEAN Non-Communicable Diseases (NCD) Network, and Dr Jeremy Lim is a Founding Member. The network is an informal grouping of healthcare experts with a shared passion and commitment to improving care for NCDs in Southeast Asia.

* This is part of a series on healthcare innovations in ASEAN