da:ns fest 2015: Artists ponder the state of Singapore’s dance scene

SINGAPORE — October is shaping up to be the unofficial “Singapore Dance Month”, thanks to two huge dance-related festivals taking place at the same time. The National Arts Council’s new island-wide dance initiative Got To Move was launched on Thursday with a diverse line-up that among other things has an event quirkily titled Dance For Your Prata.

SINGAPORE — October is shaping up to be the unofficial “Singapore Dance Month”, thanks to two huge dance-related festivals taking place at the same time. The National Arts Council’s new island-wide dance initiative Got To Move was launched on Thursday with a diverse line-up that among other things has an event quirkily titled Dance For Your Prata.

Meanwhile, the Esplanade’s annual da:ns Festival also kicked off yesterday with a show by Nederlands Dance Theatre 2, as well as other bigwigs: Ballet superstar Sylvie Guillem is presenting a swansong piece while Akram Khan will also be in town. But perhaps the most important aspect about this edition is that it’s the festival’s 10th anniversary.

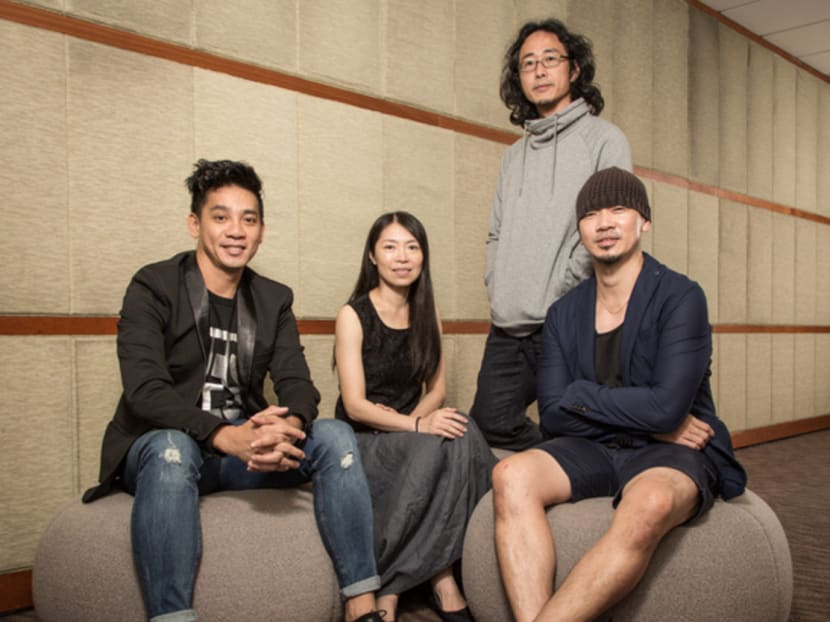

To celebrate that milestone — and the fact that Singapore has seemingly caught the dance bug — we decided to gather some notable figures in the dance scene and asked them to take stock and talk shop: The Esplanade’s Faith Tan, a veteran producer for the festival; Melissa Quek, a dancer and faculty member at LASALLE College of the Arts; THE Dance Company’s artistic director Kuik Swee Boon; and independent artists Choy Ka Fai and Daniel Kok (both of whom are taking part in da:ns and, in Kok’s case, NAC’s Got To Move, as well).

While the hour-long “roundtable discussion” was by no means exhaustive, it offered a glimpse into different viewpoints into the scene: How has dance developed during the past decade? Is there such a thing as a uniquely Singapore dance? What are the challenges dancers and choreographers face today? Is working overseas the way to go?

(da:ns festival 2015 runs until Oct 18 at The Esplanade. For more details, visit http://www.dansfestival.com/2015)

***

Q: Dance is certainly big this month. How would you compare the state of the Singapore dance scene now to, say, a decade ago?

KUIK SWEE BOON: Compared to 10 years ago — or even 25 years ago — the scene has been improving a lot. For instance, more international collaborations are taking place, which is a very good development. There’s also more international awareness about local works — from THE’s point of view, we’ve been touring to a few places in the past seven years, promoting our art overseas. (Back then) people might not have paid so much attention to Singaporean artists or local creations (overseas).

MELISSA QUEK: I think it goes through waves. In the `90s, we had a lot of companies (and) collectives such as Ah Hock and Peng Yu. And now, it’s back to the companies again, which is slowly being saturated, and then the collectives and independent artists again. But each time the wave comes, we’ve learnt something and the groups are stronger in a different way. There are so many contemporary dance companies now, with slightly stronger networking in place and stronger structures of administration that support them, which then allows them to tour.

Q: What about for an independent dance artist? What are your thoughts on going international, Daniel?

DANIEL KOK: This phenomenon of more productions and (international) collaborations happening in dance is not happening only in Singapore but globally. In Europe, there’s a very dense network of centres. In Asia, there are only, say, half a dozen cities whereby the platforms for international works are strong enough. At the moment, Australia and Europe are interested in what’s happening in Asia for various different reasons; and there might be more people passing through who are curious about what’s happening here. Quite frankly, with the European recession and funding cuts everywhere, Singapore seems to be in a good place at this moment. Infrastructure-wise, lots of things are well supported.

Q: Tell us a little bit more about international co-productions. How has that affected your artmaking, Daniel?

DANIEL: Quite significantly. I find — and I daresay, for Ka Fai, too — that in recent years, working in co-productions makes a lot of sense. Whereas, in the past, we were looking to NAC or Esplanade to wholly support independent projects. Right now, I’ve been working with a Belgian choreographer or a German art group or an Australian artist, and, in each case, they bring in production support. So it feels like a win-win situation — both parties do not need to shoulder the entire responsibility of the production. At the same time, our respective arts councils are also happy that we have taken the initiative to bring in other resources.

SWEE BOON: There are positives from logistical or financial aspects or in terms of networking. But also, from what I’ve observed, in terms of the quality of the creations, the level or standard is also higher artistically. Our dance scene has been growing artistically.

FAITH TAN: But I think what’s quite lacking in Singapore are producers of dance. People who are fully invested in presenting and producing dance. That’s something that has a long way to grow.

Q: How about you, Ka Fai, what was your journey like?

CHOY KA FAI: In 2002, I started to work with KYTV (a multimedia art collective). And at that time, it was a question of where to get support because nobody believed in us when we started. Then, I remember (former Esplanade programmer Neo) Kim Seng was bringing in shows for the Esplanade’s The Studios season, which were my first encounters (with contemporary dance). He would bring in artists such as the Leni-Basso Dance Company and Takao Kawaguchi from Japan — there was a certain openness at The Esplanade. I got to know (contemporary Singapore dance artists) Joavien Ng and, later on, Daniel.

I think a lot of my influence came from outside (Singapore). There’s a difference between dance and contemporary dance, and I was more interested in contemporary dance because it was so open — even as a visual artist a decade ago, I could still make something (related to it).

I left Singapore in 2009. It was the idea (about whether) someone in another part of the world would be interested to see a work by a Singapore artist. It was my question for the past few years: What’s my position in the global landscape?

It was also a question of practicality. I can only show a work once in Singapore, which isn’t sustainable — you make a product within six months and that’s it.

FAITH: I think Ka Fai raised a really important point about how the scale of Singapore is small and most of the creations that have been made get a chance to be shown only once here, with two — at most, three — performances. That does affect the potential growth of the work to go on so it does kind of force an artist to bring a work overseas to help it grow if there’s an opportunity.

Q: What about changes in the dance scene from the educational standpoint?

MELISSA: In the last 10 years, SOTA (School of the Arts) has popped up and the degree programmes within NAFA (Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts) and LASALLE (College of the Arts) have been refined and are growing. I don’t know if these have benefitted the companies yet, though. I don’t know if we’ve produced enough technically strong students (for the dance companies).

SWEE BOON: We have eight dancers and five or six are from LASALLE. That’s been the vision of my company, to try to have at least two-thirds of the dancers from Singapore. In terms training, each school has its own vision. I know LASALLE is focused more on contemporary dance. NAFA used to look for the so-called Asian contemporary dance but these past few years, it seems to be more focused on ballet. I do think we could still improve communication between schools and professional companies to find out each others’ needs, because obviously there are now more companies, such Frontier Danceland, Arts Fission, Re:Dance Theatre, with their own direction.

A lot of western (schools of thought) is about training dance artists, not dancers. But in Asia, it depends on the vision of the school. NAFA seem to focus a lot on technique and there’s obviously a need for this — Singapore Dance Theatre would need dancers with a very good technique. But for THE, for example, we’re looking for dancers with more individual qualities.

KA FAI: I think Singapore has produced very good dancers, but what kind of dancers? When Japanese choreographer Hiroaki Umeda did an Esplanade commission, he was looking at the dancers (in Singapore) and commented that they had very good technique but he wanted something else. In the end, he chose Taiwanese and Cambodian dancers. There’s the situation where even good dancers don’t get so much opportunity because they cannot differentiate themselves in the Asian context.

Another example was when (Belgium-based choreographer) Arco Renz came in with Cambodian dancers for the work Crack. It was commissioned by the Singapore Arts Festival but no Singapore dancers were involved — except for the dramaturg, who was living in Bangkok (Tang Fu Kuen).

I think we are (also) crying out for choreographers because I don’t see many. I can’t really say much about how we create choreographers in Singapore but maybe recent efforts, such as Daniel’s workshop for emerging choreographers at this year’s da:ns Festival, is giving some space for them to experiment and be mentored.

Q: So it’s the issue of choreographers….

SWEE BOON: We need them, too. To move the scene forward, we need to see more new local work, good and original work. That’s why we’re doing the M1 Open Stage (a platform under THE dance company’s annual M1 Contact dance festival showcasing new work). The company also had its own Emerging Choreographers platform and the NAC initiated (the choreography contest) SPROUTS.

DANIEL: It’s not a question of dancers versus choreographers but of people working in dance having a personal practice. Because I found, especially in my recent workshop for people who saw themselves as independent artists in dance, that there was a need to stop some of the participants from jumping quickly into boxes. Like “You’re a dancer”, “You’re a choregrapher”, “Now you’re improvising”, “Now we are creating”.

What if we unpack these notions a little bit? For many of them, when they’re not being a dancer, they’re people standing in front of a dancer telling them what to do — and that is a choreographer. But maybe it doesn’t have to be like this anymore. The way Ka Fai is working with dance, you could say he’s not choreographing. But we are all practicing in dance in different ways and I find that refreshing and interesting. It’s not a question of simple categorisation.

MELISSA: Actually, that’s one of the things that has happened in the last 10 years: The definition of dance has been broadening and people are accepting it. Yes, there was a broad definition in the past, but people didn’t accept it. Now, more students and mainstream audiences are accepting these wider definitions or realising you don’t have to pigeonhole things.

For LASALLE’s dance curriculum, we want to get students to be as employable as possible, so we try to put them on as many pathways as they can go. On one hand, we’re trying to get them to be as strong as they can be technically but, at the same time, we’re also trying to encourage them to become independent, dance artists and not just choreographers. But (the diversity) has been helpful — introducing our students to people like Ka Fai and Daniel and their works, they can start thinking “Okay, there are many pathways for me, there’s a lot that I can do.”

Q: Is there such a thing as a Singapore dance aesthetic?

MELISSA: Going back to Ka Fai’s point about international choreographers, that’s a huge question that has been plaguing me for a long time because some of our dancers are grounded in certain traditions, which have informed their bodies and their practice. So you have someone with a very strong background in Bharatanatyam that they can work into a contemporary idea with other people.

But some of my students don’t have any of these. Some are not grounded in a particular Chinese or Malay dance form. For some, the grounding is in hip-hop or breakdancing. I have a theory on what the Singapore aesthetic is — it’s our openness to various forms coming together. I think that very often, especially for South-east Asian artists, it has been “I am trained in this form and, as I contemporise it, we work it in a different way and with other people.”

But I think what’s really interesting about the Singaporean artist from (pioneering dance artists) Mrs Santha Bhaskar’s and Madame Goh Lay Kuan’s time is they believe in the idea that the dancer should learn multiple forms. I think that is something we’ve had in Singapore’s dance history that isn’t really replicated elsewhere, this multiple forms of different cultures.

Q: But the artists in this roundtable come from completely different places: There’s Swee Boon’s ballet background from SDT, Ka Fai came from the visual arts and Daniel comes from a different background, too.

SWEE BOON: I’m not so worried about whether dance is “traditional” or from the West but simply looking for what’s unique. I guess that’s what we should think about and not worry about whether it represents something “Chinese” or whatever. But while THE doesn’t use cultural dance techniques, there are some influences in our training — the way we use our breathing or how we understand energy come from traditional training forms like tai chi. Even Martha Graham’s technique has (Asian influences).

DANIEL: I grew up Singaporean in a way that made me believe that I don’t own anything. That there’s an identity crisis and that I have no culture. So when I started dancing at 21, and asking what my tradition was and where I came from, I felt that it was Paula Abdul and Janet Jackson. What if it’s not ballet or Chinese dance or taichi but Paula Abdul? That’s how I feel. And the older I get, the more desperate I am in trying to find my way back to Paula Abdul — but that’s a conversation for another day!

But I often wonder: I think I’m open but I’m really not. I do agree that there is this kind of willingness among Singaporeans — whether it’s the younger students or the most experience artists, everyone is very eager to learn. I daresay it’s the common denominator of a sponge. But I also question myself whether I’m simply replicating all the stuff I learned in Germany and Belgium and England — that I’m just being a “banana”.

As for uniqueness, I struggle with this quite a lot. Because at the end of the day, the issue with being unique seems to be about having to make things as novel and as new to excite people and it’s like, is this what I’m supposed to do?

KA FAI: I don’t believe that there will be a unique Singapore dance production in contemporary dance. It’s both an advantage and a disadvantage that we are without any cultural baggage like a contemporary dance-maker from India. We are free to do what we do. Like, if I show my work in Europe, the “Singapore” doesn’t mean anything. Everywhere I go, it doesn’t make any difference whether I say I’m from Singapore or not from Singapore.

I also live and grew up in Singapore, and there’s a confluence of different forms and influences. I remember, when Daniel and I were in Ljubljana, a Japanese butoh dancer who saw (Daniel’s) show came up and said that he had wanted to see something more Asian but didn’t feel there was anything Asian or Singaporean about his work — how we’re received as Singaporean artists is interesting.

MELISSA: I actually think the one thing that does sort of distinguish the Singapore artist is that the question of identity is always at the back of our minds. Whether we’re deliberately addressing it in our work or avoiding it, it’s always there in us. The other thing is the idea of something Singaporean in comparison to something else. I think it’s really interesting when (local) dance companies work with South-east Asian artists and find the overlaps, like when THE had (Indonesian choreographer) Boi Sakti come in — it was pretty interesting seeing what was happening to the bodies of Singapore-trained dancers.

FAITH: I can only say, from a programming perspective, that it’s not a consideration. I don’t at all think I’m looking for an artist that is uniquely Singaporean, who will represent to the audience what Singapore can possibly be. I think it’s very dangerous if you start from there and create a show or a festival based on that.

Q: Shall we talk about the challenges that people in the dance scene face?

KA FAI: I think Singaporean artists are being treated too well. The infrastructure and everything (makes it) too comfortable, I think. When you get comfortable you don’t ask so many questions.

SWEE BOON: I do agree with what Ka Fai says about the environment being sometimes too comfortable, and people simply accepting certain conditions instead of questioning these. This kind of mindset has been passed from schools. So when we accept students from LASALLE or NAFA, technique and training is one thing, but we’re also looking to see if they have their own characteristics.

FAITH: I’m not sure, though, that having less institutional support would make people better artists. Because it was not so long ago that there wasn’t so much access of support for dance and people were really struggling with limited funds — but I don’t think it necessarily equated to better quality work.

Q: But better support does equate to more opportunities to create more work, doesn’t it?

FAITH: Yes, I think so. Obviously, if there are more people able to get more funding, they can create this volume of productions. But that, in fact, is its own problem and some of us feel that there is a lot of chasing-the-production, going into the next one very quickly, but with very little time for reflection and workshopping, which puts us all in a mode of just producing and producing. It’s this wheel of producing and consuming and instant-ness.

DANIEL: Having spent a little bit more time in Singapore this year — because I’ve been away a lot in the past five, six years — I feel like there’s an overproduction (of works) in Singapore. And it’s not even a question of quality because there’s not even time to think about that — there’s just so much going on, so much money sloshing around in dance and everything else. I was really stunned by the NAC’s latest effort, Got To Move. It’s not up to me to say this or that shouldn’t happen — because I’m also a beneficiary of (Got To Move) — but I do wonder, what does all this activity answer to in the end?

FAITH: I feel like it has a lot to do with audience development as well. Through the 10 years (of da:ns Festival), you do see there are definitely more audiences coming and embracing dance, which is great. They’re very curious and interested. But I think so much more can be done in terms of actually engaging people to not just come and watch a performance, and expect to be entertained. I think what’s missing from a larger majority of the audience is investing in a relationship with the local artists and the local dance community, and journeying with their body of work. Of course, we do have dance supporters who are very loyal but I think majority of audiences sometimes do come with very fixed expectations of what they want the dance show to give them.

SWEE BOON: Artists need time to do research, make mistakes, until we put something onstage. We have to allow ourselves to go through a long process to produce new work, but as you know, in Singapore, companies have seasons and we have to come up with a new production almost every three months. That’s the model.

KA FAI: I think Swee Boon and THE are in a very difficult situation because I understand how it works: You have to produce to get the grants.

Q: Do you feel there’s a kind of Singapore dance community, in the same way that, say, there’s this image of a Singapore theatre community?

DANIEL: I don’t long for a community in the sense that everybody must support each other by literally going to see each other’s work and sayang-sayang… I think that the field of operation is so wide now and I can be supportive of an artist who works totally differently from me but we don’t have to agree (on everything) and I’m quite happy for the vagueness to continue.

KA FAI: The presence of THE, a mainstream dance company, is necessary to have in the whole dance ecology, because without these, there will be no fringe. You need to have all these different players to create a whole scene that is vibrant.

MELISSA: From the outside looking in, we might pick up certain things like, say, Cloud Gate for Taiwanese dance. But there’s also so many other companies doing such different work (there) and I think it’s a healthy ecosystem when you have different people doing different types of work. That keeps things growing, as opposed to “This is the main company that represents us and the whole world will see it.”

Q: What about the idea of audiences, does the scene have enough?

FAITH: I feel, within the 10 years of da:ns festival, and the wider programming of dance at Esplanade, we have made strong progress in developing audiences for dance in Singapore. But I think audience development is a challenging area within all fields of art, around the world, and ideally needs a holistic ecology to support its growth — from education to programming to policy making, this takes time to come together and I think we are in a good position in Singapore to work deeper together in growing these areas.

KA FAI: I wonder about that. The biggest arts festival in Singapore just recently presented, like, 14 dance shows in two weeks (the Singapore International Festival of Arts’ Dance Marathon series). How many people or what type of audience came to see these and do they really appreciate the effort in bringing this intense dance marathon to Singapore? Do we have the audience in Singapore? That’s what I’m thinking about.

MELISSA: I feel like it’s the same people. Like, definitely, for me, I encourage my students to watch shows but at the same time, we feel really stretched because we’re trying to watch so many shows as we can, partially to expand the scene but also to be supportive. I keep telling them to go and the shows keep clashing and they’re tired — it is a bit too many for us.

SWEE BOON: It’s true that there are so many things happening outside. It’s good because it shows there’s a lot of support, financially, and there’s a desire from artists to also create work. But I guess now is the time to know what we stand for as artists.

DANIEL: I think taking a position is really important. Rather than producing one show after another, what are you really about, what are you looking for? What are you investigating, whether you’re a company or an independent artist or a freelance dancer.