The annual investment guessing game

In 1903, the president of the Michigan Savings Bank advised Henry Ford’s lawyer not to invest in the Ford Motor Company. “The horse is here to stay,” he said, “but the automobile is only a novelty — a fad.”

In 1903, the president of the Michigan Savings Bank advised Henry Ford’s lawyer not to invest in the Ford Motor Company. “The horse is here to stay,” he said, “but the automobile is only a novelty — a fad.”

Not too long ago, political sages predicted that Donald J Trump couldn’t possibly win the Republican presidential nomination, let alone be elected President of the United States. We all know how those predictions turned out.

As we head into a brand new year, really smart people will be churning out new predictions of how the markets will perform. It is no coincidence that this is typically the time when investors review their investments and decide how they should be positioned for the future.

Most of us will agree that it is not possible to predict market performance, but some of us will still assiduously search for clues from experts — the more famous, the better, as though being renown correlates with predictive accuracy.

These forecasts are almost always followed by recommendations on how to capture the next big opportunity or avoid the next big market collapse. What should one do when faced with such a variety of recommendations, some of which may be conflicting?

FULL SPECTRUM OF OPINIONS

Among the various market outlooks and forecasts released by financial institutions, there are bearish views on how a China slowdown, a North Korean nuclear attack, high market valuations and rising inflation will spell the end of the current bull market.

On Jan 2, for example, the Eurasia Group said: “If we had to pick one year for a big unexpected crisis — the geopolitical equivalent of the 2008 financial meltdown — it feels like 2018.” (Note that its forecast for 2017 was that it would be a period of geopolitical recession, given a volatile political risk environment that was as important to global markets as the economic recession of 2008.)

On the other hand, there are also bullish views on how Trump’s tax reform plan, global economic growth and consumer spending will continue to drive the bull market this year and beyond.

Other “outlooks” by experts avoid taking a stand, and they recommend buying property, gold or cryptocurrency instead.

It is therefore hardly surprising that many people end up concluding that investing in the stock market is complex and they need to find the “right expert” to help them buy and sell at the correct times. That is perhaps why Steve Forbes of Forbes Magazine once said: “You make more money selling advice than following it.”

Consider, too, the dire warnings bandied about by many investment professionals in the last six months: Stocks are “too expensive” and it would be better to hold cash, or wait for a better time to invest.

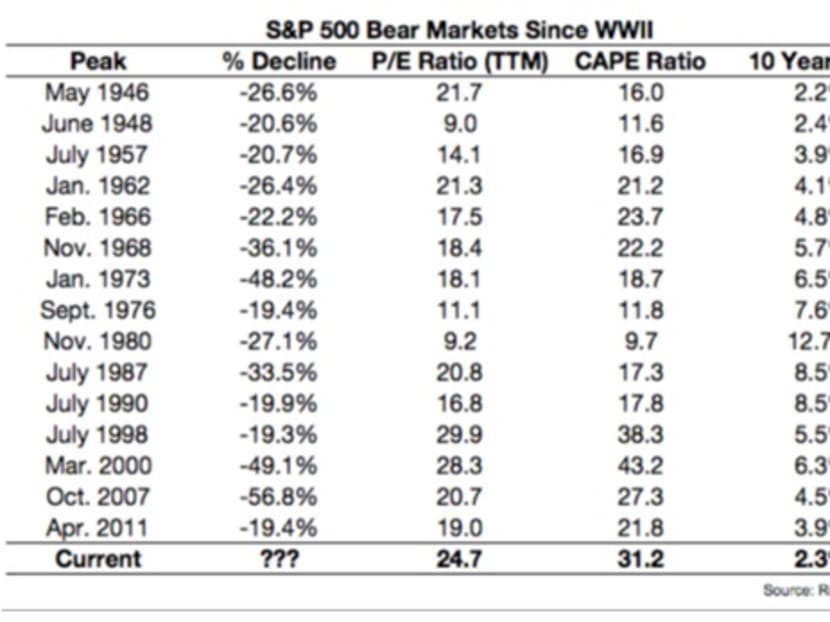

The problem with such predictions is, firstly, we have to determine the threshold for stock valuations being too high. If we take US stock market data, the Standard & Poor’s (S&P) 500, and analyse past bear markets, the evidence shows no apparent correlation of high valuations with market declines.

Using a simple price-earnings (P/E) ratio and the increasingly popular Shiller cyclically adjusted P/E (CAPE) ratio, we also see that there is no definitive number at which we can pinpoint a potential bear market.

Bear markets happened when the P/E ratio was over 28 (high valuation) and when it was nine (low valuation). So, when exactly should an investor sell out of stocks to hold cash?

(Click to enlarge)

The second problem with such predictions is that they force the investor to make two decisions. If the investor decides to heed the advice of selling stocks to hold cash, he or she must then decide when to buy back into the market.

In Nobel Laureate William Sharpe’s 1975 study, Likely Gains from Market Timing, he noted that investment practitioners required at least a 70 per cent accuracy or more in their market timing calls in order to beat a dumb diversified buy-and-hold market portfolio.

If someone manages to get a “sell” call correct 70 per cent of the time, and a “buy” call correct also 70 per cent of the time, they would have an overall accuracy rate of just 49 per cent. That is, really, a 50/50 chance — just like flipping a coin.

Once you deduct trading costs and taxes, you would be hard-pressed to break even from your efforts.

An interesting study conducted by CXO Advisory Group compiled and graded a list of forecasts and predictions by well-known market timers. It found that the forecaster who came closest to the 70 per cent yardstick only had 68 per cent accuracy, and was thus unable to beat the buy-and-hold strategy.

Surely, all such predictions and market forecasts should be backed up by verifiable research. Or is it?

MARKET MOVEMENTS

The majority of the work by analysts is likely to be based on forward estimates, which are ever changing according to the latest news and market sentiment.

For investors, some of the key information they want are the causes of daily price fluctuations and what drives the changes in market returns.

Before anyone invests in a company or a business, most would want to know how much money that business was making, and whether the cash flow was positive or negative. Obviously, investors only want to invest in companies which have a positive cash flow, both now and in the future, so that the expected return from investing in the company will be positive.

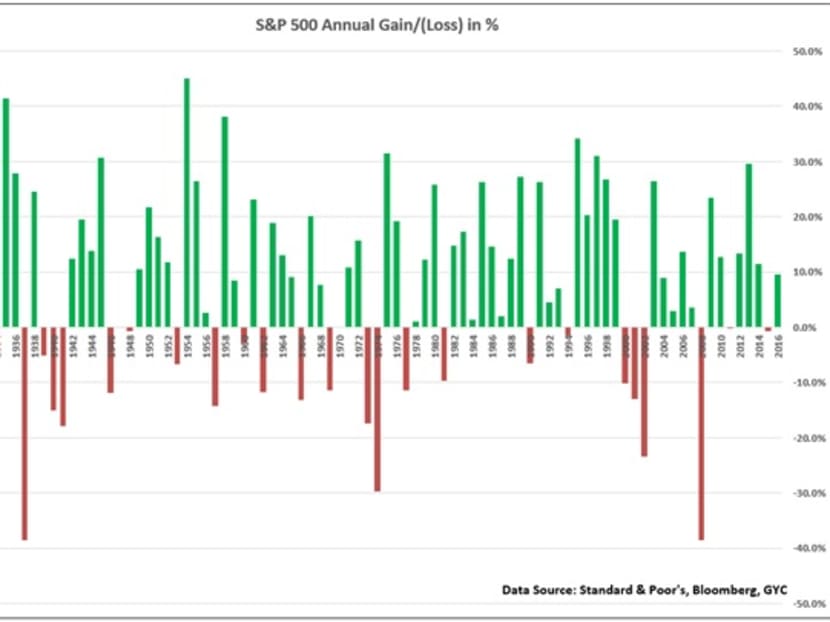

To prove that, in aggregate, investors can expect a positive return for stocks, we look at the long-term returns of stock markets via the S&P 500.

Over the past 89 years since 1928, the chart below shows that 60 had positive returns and 29 had negative, giving the stock market a batting average of about 67 per cent.

New market highs have, historically, not always been followed by negative returns. Thus, regardless of where the market is at presently, the expected return is positive.

(Click to enlarge)

If this is the case, why then do so many people end up getting negative returns? Apart from market movements (which one cannot control), one of the main culprits is investor behaviour (which one can control).

The relatively new field of behavioural finance has shown that humans make poor decisions when it comes to investing their money, including not recognising bad advice. For example, humans tend to exhibit herd behaviour, driving prices to extremes whether up or down, and our brain tends to forget our long-term plans in order to chase short-term satisfaction.

Ultimately, the evidence shows that investors are better served by sticking to a properly constructed plan and investing in a diversified portfolio with the correct asset allocation.

Recognise that no one can predict market movements with sufficient consistency to beat a diversified buy and hold portfolio. Believing in this alone reduces stress levels and helps you avoid earning a lower return in the long run.

Ruchir Sharma, chief global strategist at Morgan Stanley, wrote in The New York Times about a week ago that leading economists have consistently missed big market turns and have not predicted a single US recession since a half-century ago.

They have also missed many revivals, including the unusually broad global expansion of 2017. As such, by trying to time the markets just by following forecasts and outlooks, investors risk missing the majority of the time when the stock market generates positive returns.

So follow the evidence, and stay the course.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Aw Choon Hui is the deputy chief executive officer of GYC Financial Advisory, a licensed financial adviser and registered fund management company.