The Future of Work: Days that drone on? Not for these UAV pilots

SINGAPORE — They fly the friendly skies, but not in the cockpit of a plane. Instead, a small but growing pool of drone pilots here spend their work days cruising over the Malacca Straits to capture footage of a "flying ship", mapping out golf courses, and scouring rollercoasters in the dark of night for abnormalities.

Late last year, a study by consulting firm McKinsey estimated that almost a quarter of work activities in Singapore could be displaced by 2030. At the same time, however, a vast amount of jobs will be created, with new technologies spawning many more jobs than they destroyed, the study pointed out. The introduction of the personal computer, for example, has enabled the creation of 15.8 million net new jobs in the United States in the last few decades, even after accounting for jobs displaced.

In a new weekly series, TODAY looks at The Future of Work — the emerging jobs fuelled by technological advancements which may not even have existed a few years back, but are set to proliferate within the next decade or so. First up: Drone pilots.

SINGAPORE — They fly the friendly skies, but not in the cockpit of a plane. Instead, a small but growing pool of drone pilots here spend their work days cruising over the Malacca Straits to capture footage of a "flying ship", mapping out golf courses, and scouring rollercoasters in the dark of night for abnormalities.

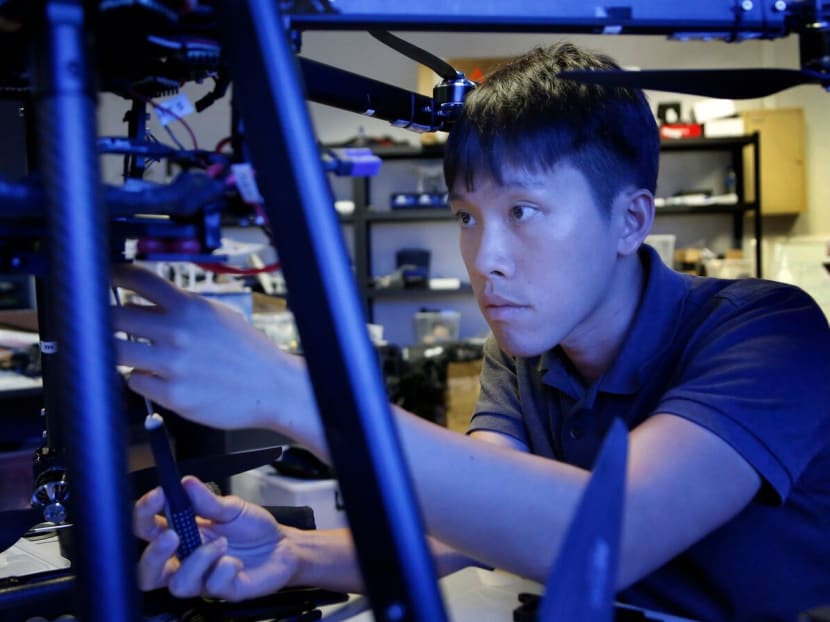

For Mr Cheng You Zhi, 26, a drone pilot and operations lead with homegrown drone company Avetics Global, one project required him to fly a craft — armed with a light emitting diode (LED) — at 3am to detect cracks and irregularities in rollercoasters at a theme park.

Avetics’ services were engaged as part of a trial, Mr Cheng said, and working in a team of three, he flew the drone, while a colleague operated the camera, and another looked out for potential safety issues.

For Mr Cheng You Zhi, 26, a drone pilot and operations lead with homegrown drone company Avetics Global, one project required him to fly a craft at 3am in a theme park. Photo: Raj Nadarajan/TODAY

The assignment, which went on for four hours save for a break every 20 minutes to replace the drone’s batteries, was “a bit disorientating”, Mr Cheng confessed.

This was because he had to crane his neck “all the way up”, and the only thing visible was the drone’s LED. “The only good thing was it’s not hot (to work at night),” he said.

Drone pilots work in many types of commercial and industrial projects, which can range from security surveillance at major public events to building inspections and artistic photography.

They also tinker with drones that can be retrofitted to the demands of an assignment, such as fitting sensors to detect gas leaks.

Based on figures from the Civil Aviation Authority of Singapore (CAAS), the profession seems to be getting popular in Singapore. The authority told TODAY in March that it issued 400 operator permits for the 2017/2018 financial year (FY) up till end-February, which was nearly a two-fold jump from the 215 permits issued in the previous FY. For FY2015/2016, it handed out 117 permits.

Since laws were introduced in 2015, a total of 800 drone pilots have been covered under these permits from the CAAS.

CHASING A ‘FLYING SHIP’

Recounting one of his most memorable assignments, Mr Cheng said it was the time when he was out in the Straits of Malacca to shoot aerial video footage of a “flying ship”, called the AirFish 8, for a science documentary.

The AirFish 8, which glides on an air cushion metres above seawater, is produced and distributed by Singapore-based company Wigetworks.

Working with a British production crew, Mr Cheng operated the drone from a small boat as the AirFish 8 zipped over water.

Aside from having to launch the drone by hand, the full-day assignment was made more challenging as filming had to be done while the AirFish 8, which moved faster than the drone, was airborne.

He said: “The AirFish is fast and needs to be travelling at 60 to 70 knots (about 110 to 130km/h) to be airborne. We couldn’t keep up with (its) speed.”

Mr Cheng’s drone was capable of flying at speeds of about 38 knots up to 20m in the air.

Unlike other ships, which can pick up or reduce speed to allow for filming, the AirFish 8 is unable to do so when in operation.

For other drone pilots, the impact of their work was felt immediately.

Mr Nicholas Hon, 30, was on the lookout for potentially dislodged tiles on a roof while conducting inspections for an entertainment and hospitality facility last year when his drone spotted a critical fault that “could kill”.

Several tiles had become dislodged from the roof, posing an imminent danger if they came crashing down.

Mr Nicholas Hon, a former unmanned aerial vehicle pilot with the Republic of Singapore Air Force, finds job satisfaction from being able to make his clients’ jobs easier. Photo: Raj Nadarajan/TODAY

“The client was shocked that there was something like that, and immediately after the flight, I transferred the images to him. He sent an email to management straight away (to tell them) that they need to fix it immediately,” said the former chief pilot and senior operations manager with Garuda Robotics, a robotics and artificial intelligence technology company.

Mr Hon, a former unmanned aerial vehicle pilot with the Republic of Singapore Air Force, finds job satisfaction from being able to make his clients’ jobs easier.

“At the end of the day, that’s why we’re using drones. We’re trying to provide this solution... to give another angle or help you to get your work done by the air.”

BEHIND THE SCENES

While drone-flying is the core of the job, much work goes on behind the scenes — as early as several weeks before take-off — to ensure things run smoothly.

After they get an assignment from a client, the pilots and their colleagues will do a site recce to assess the risks, and note the potential hazards to property or people. This happens at least a fortnight before the flight, Mr Hon said.

Following a discussion on the risks, the team then applies for an activity permit from the CAAS to fly in the specified area.

This includes drawing up a flight plan detailing the flight path, as well as the number and position of the drone pilots and observers involved in the project, for instance.

Operators also have to identify hazards and put in place control and recovery measures to ameliorate the risks.

Permits are generally approved between five and 10 working days, Mr Hon said.

Mr Muhammad Aljufri, 32, a drone pilot with security company Aetos, said that on the day of the flight, more site checks are done to ensure it is safe to fly, as conditions could have changed from the initial site inspection.

Pilots conduct a test run before the flight to check for problems such as electromagnetic interference from buildings, which could interrupt operations.

RISING DEMAND

Avetics’ chief executive Zhang Weiliang, 31, said more companies are looking at ways to harness drones to perform tasks that are labour-intensive and dangerous.

Firms are already trying to equip their workforce with drone-flying skills, a trend that is taking off at his company’s training academy. The academy imparts skills to firms in sectors such as media, telecommunications, defence, and construction.

“We’re definitely seeing an uptick in drone training in recent months… it’s going to be much stronger in the coming years,” Mr Zhang said.

While Garuda Robotics’ eight licensed drone pilots come from backgrounds as diverse as software development and production, Mr Hon said he looks for applicants with some form of drone flying experience.

Experience in building hardware or drones, and knowledge of drone systems, are also a plus. What applicants studied in school matters less, he added.

At Avetics, all four of its drone pilots are engineers by training as they build and modify the drones.

Persons operating drones weighing more than 7kg, or for uses other than recreation or research, must hold an operator permit from the CAAS, and they are tested by an assessor from the authority.

As part of the assessment, pilots have to execute manoeuvres, which could include hovering in various orientations and landing at a designated spot.

Avetics and Garuda Robotics said trainees enrolled in their programmes can be armed with the competencies needed to undergo the assessment in as short as two to five days.

The CAAS said that the demand is reflected in the “steady rise in the number of operator permit applications since June 2015”.

“We expect the number of such applications to increase further, with the growing deployment of drones for commercial and industrial purposes,” its spokesperson said.

At Garuda Robotics, the number of commercial projects it handled doubled between 2016 and last year, although the company did not disclose figures.

Mr Robin Littau, Aetos’ vice-president for business development, said the industry is “only going to continue to grow”.

With the one-north science hub and business park designated Singapore’s first drone estate, he said drones could be used to deliver goods in the area, for instance.

While Aetos’ drone pilots currently also double up as installation and service technicians, Mr Littau is confident that the company will have staff members focused on only operating drones in the future.

LOOKING INTO THE CRYSTAL BALL

While drones are largely operated by humans at the moment, there is the prospect that they could become fully autonomous in the future. Already, start-ups such as Israeli company Airobotics have built self-flying drones that do not require human involvement.

Still, Mr Zhang is confident that those with expertise in drone systems are here to stay.

“You still need people who understand the drone, the behaviour, and the technology so that you will then know how to deploy them, and what some of the limitations are. But maybe instead of that person flying one drone, he will oversee 10 or 20 drones.”

Mr Hon does not see fully autonomous drones taking flight in the near future. “Most regulators would still want a human to be there… whether it’s in a room or out there looking at a drone and flying within the line of sight,” he said.