Improving the welfare of Singapore’s migrant workers

Crafting labour policies for low-skilled foreign workers is challenging. Moral and economic imperatives do not necessarily coincide. These workers, being neither enfranchised citizens nor fully participating members of society, further raise the complicated question of how far their welfare should be considered if it comes at the expense of citizens.

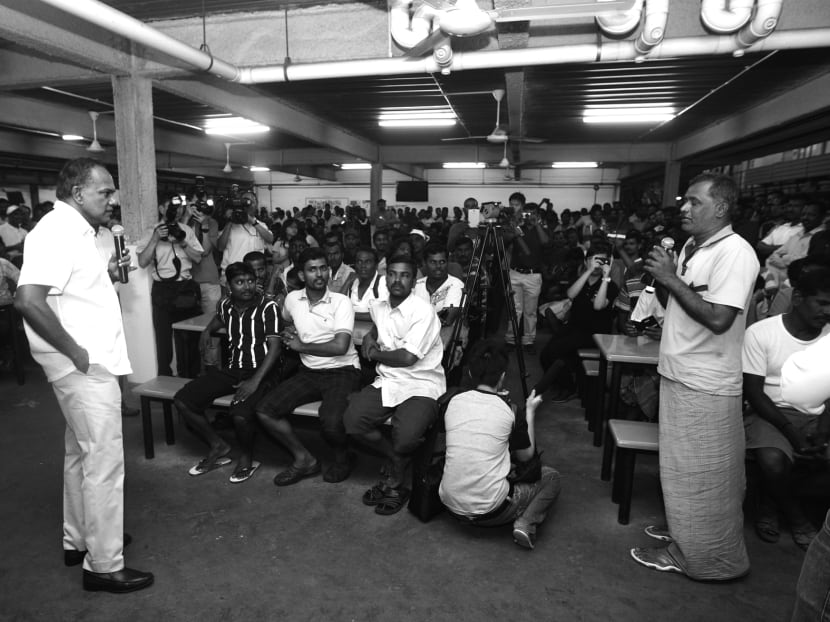

Minister K Shanmugam chatting with foreign workers at their dormitory after the Little India riot. The Government has ruled out work-related grievances as a cause of the incident. TODAY FILE PHOTO

Crafting labour policies for low-skilled foreign workers is challenging. Moral and economic imperatives do not necessarily coincide. These workers, being neither enfranchised citizens nor fully participating members of society, further raise the complicated question of how far their welfare should be considered if it comes at the expense of citizens.

In Singapore, the question of how these workers have to be treated has become increasingly pressing following two major foreign-worker-related incidents. In December 2012, about 100 Chinese national bus drivers employed by SMRT protested in response to what they perceived as unfair wages. It was the first labour-related strike in nearly 25 years.

Nearly a year later, there was a large-scale riot by South Asian workers, following the death of an Indian construction worker due to a traffic accident. The situation escalated and soon turned into a violent protest. Work-related grievances have been flagged by some as a possible reason for the escalation, though the Government has ruled this out.

Low-skilled foreign workers constitute nearly 15 per cent of the population of Singapore. Hailing primarily from countries such as China, India and Bangladesh, these workers are not allowed to switch jobs; their work is laborious and compensation is modest.

Economic factors drove these workers to Singapore, hence work-related policies would be the most effective lever in improving their welfare. Ideally, these policies should minimise cost for consumers and employers. This would also engender greater political will. In this spirit, allow me to make some policy proposals.

REGULATING AGENTS, PAYMENT OF WAGES

Overseas employment agencies are believed to play a considerable role in the employment of many foreign workers. There is a risk that these agencies might present a distorted image of working conditions and charge exorbitant fees for their services.

Some workers have been known to work for long periods just to pay off the agency fees. Because of the high fees, many workers are beholden to their employers.

Philippines, which is a huge source of foreign labour for Singapore, has been proactive in protecting the rights of its citizens; overseas employers are legally allowed to recruit workers only through agencies registered and licensed by POEA (Philippine Overseas Employment Administration). Employers have to be responsible alongside the POEA under Philippine law with regard to any claims and liabilities raised concerning the implementation of employment contracts.

It is unlikely that countries such as India and Bangladesh would come up with such comprehensive legislation to protect their citizens. The want to find meaningful employment for the burgeoning working population is likely to be a greater priority than ensuring their labour rights.

However, Singapore could take the lead with more comprehensive regulation of employment agencies. Currently, regulations stipulate that fees of local employment agencies cannot exceed more than two months of the worker’s salary. However, there is no cap on the amount that the overseas employment agencies obtain through the workers. Accrediting overseas employment agencies, which observe a pre-set cap, would be the only way to ensure that workers are not burdened with undue debt.

Most of the complaints from unskilled workers are wage-related. As companies are not required to pay their workers through their bank accounts, many workers have found it difficult to provide evidence for their complaints. It is laudable that the Government is actively exploring the possibility of mandating electronic payments, following the suggestion of Member of Parliament and head of the Migrant Workers Centre Yeo Guat Kwang.

With electronic payment, steps can be taken to allow workers to immediately remit a share of their income to their loved ones. This would encourage greater fiscal discipline, limiting the possibility of workers spending large amounts of money on gambling and excessive alcohol consumption.

Beyond salary, Mr Yeo’s suggestion that the Ministry of Manpower should mandate employers to provide the terms of employment also has merit. Currently, employers are required to state the fixed pay when applying for workers’ permits, but not the full terms of the employment. Mandating the provision of the complete terms of employment would ensure that migrant workers are clearly aware of their rights and reduce any mismatch in expectations between both parties.

ASSESSING EMPLOYERS MORE BROADLY

Economic incentives need to be properly structured to ensure that employers behave responsibly. Currently, employers are required to submit a S$5,000 bond to the Government for every non-Malaysian worker they hire on Worker’s Permit. This sum is returned if the employee does not overstay.

This has created a perverse incentive for employers to hire repatriation firms to send their employees back once their contracts end. Some of these repatriation companies have been reported to resort to violence.

The Government could perhaps use a broader set of criteria to assess these companies employing foreign workers. In addition to successful repatriation, other criteria, such as the number of workplace safety breaches and the condition of the workers’ dormitories, could be collated, and a rating could be created. This rating then could determine the fraction of the initial bond they get back.

This track record could be used as a deciding factor in the awarding of government tenders. This way, employers would have greater incentive to ensure the welfare of their workers.

The International Labour Organisation’s Declaration of Philadelphia pronounced emphatically that “labour is not a commodity”. Low-skilled workers cannot be treated as just cogs in the economic machinery. They are individuals whose rights to a fair-paying and dignified job must be respected.

The conflicting interests of consumers, employers and workers do present a serious challenge. Recognising this, the declaration affirmed that effort has to be undertaken “with unrelating vigour within each nation” to ensure that workers’ rights are not encroached.

Improving the welfare of low-wage of workers does not always have to be cast as a zero-sum game. There is much that we can do that does not come at the expense of society.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Muthhukumar Palaniyapan is an undergraduate at New York University Abu Dhabi with a keen interest in politics and public policy.