Mindef invites hackers to test public-facing systems for vulnerabilities

SINGAPORE — In a first for a government agency here, hackers will be invited to put the Ministry of Defence’s (Mindef) public-facing systems — including the National Service (NS) Portal — to the test, in order to expose vulnerabilities.

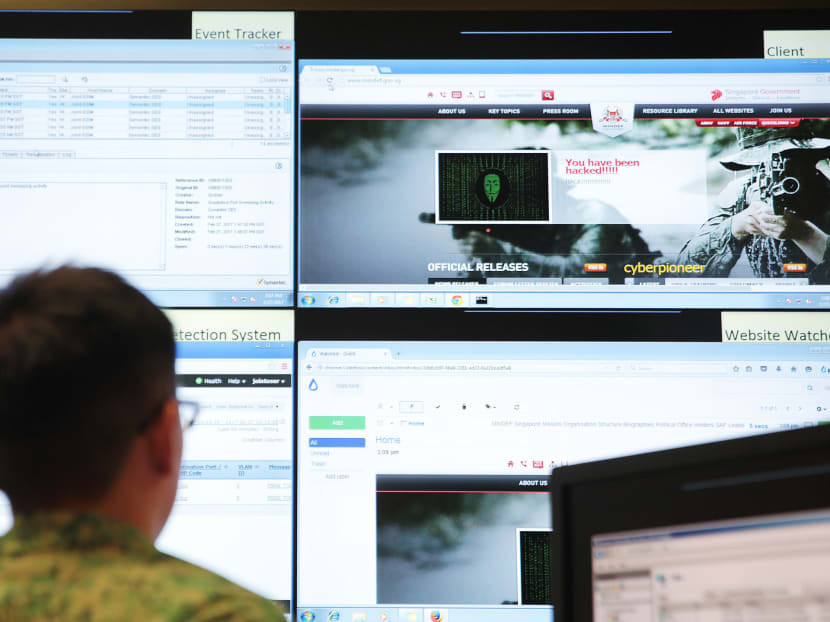

A simulated cyberattack at Mindef's Cyber Defence Test and Evaluation Centre (CyTEC). TODAY file photo

SINGAPORE — In a first for a government agency here, hackers will be invited to put the Ministry of Defence’s (Mindef) public-facing systems — including the National Service (NS) Portal — to the test, in order to expose vulnerabilities.

The move, announced by Mindef’s defence cyber chief David Koh on Tuesday (Dec 12), will involve about 300 “white-hat” hackers — computer-security specialists whose role is to break into protected systems to test their security, before hackers with malicious intent strike.

The Cyber Security Agency of Singapore (CSA) is also in talks with some of the 11 critical information infrastructure (CII) sectors which have expressed interest in exploring a similar programme for their public-facing systems, its deputy chief executive for development Teo Chin Hock said in a statement. CII sectors include infocomm, land transport and water.

Under Mindef’s programme, hackers will receive “bounties” or rewards for bringing to light “valid and unique” vulnerabilities.

These range between S$150 and S$20,000, going by programmes run previously by global bug-bounty company HackerOne, which Mindef has engaged to run its programme from Jan 15 to Feb 4.

The rewards will hinge on the number and quality of the vulnerabilities exposed, and are expected to cost significantly less than a commercial cyber-security vulnerability-assessment programme, which can cost up to S$1 million. In contrast, the new bug-bounty initiative is estimated to cost around S$100,000, said Mr Koh, who also heads the CSA.

Eight of Mindef’s Internet-facing systems — including the Mindef and Defence Science and Technology Agency websites, and the NS Portal — will be part of the exercise.

It will not involve the Singapore Armed Forces’ operational systems, which are not public-facing. Two-thirds of the 300 participating hackers are expected to be overseas-based, such as in the United States and Europe, with the rest from Singapore.

Mr Koh acknowledged that the programme comes with some risks, including increased traffic to its websites. Those who are not registered with the programme could also try to probe the ministry’s systems and pick up vulnerabilities, while the hackers engaged may turn rogue and exploit the loopholes or publish them online.

To reduce such risks, Mindef’s internal defence teams will be on alert. The selected hackers, many of whom do so for a living, are also experienced in the field and have their reputations at stake. It is “unlikely” they would turn rogue, said Mr Koh, adding that HackerOne did not encounter rogue hackers when it ran a similar programme for the US Department of Defence.

Mindef will also take steps to “mitigate” slow service or disruptions to its web systems that could occur during the programme.

Cyber-security professionals told TODAY the risks were minimal, given Mindef’s strict security protocols and the separation between its public-facing and operational networks.

Mr Ali Fazeli, founder of cyber-security firm Infinity Forensics, said a website defacement was the worst-case scenario, which is still unlikely.

Added IT security consultant Kamarudin Osman, who is also a certified ethical hacker: “Mindef has very stringent security controls… There’s always a residual risk, but the probability of it happening is very low.”

In Singapore, white-hat hackers are certified by information-security training providers such as EC-Council.

Mr Fazeli said ethical hacking was one of the best ways to pinpoint vulnerabilities. Professional firms may have limited manpower resources and knowledge, whereas ethical hackers are “more updated and have a variety of knowledge”, he said.

Apart from the US Department of Defence, the US-based HackerOne has run similar programmes for corporate giants such as Google and Twitter.

Its pilot initiative at the US Department of Defence, which ran from April to May last year with five public-facing websites, turned up 138 vulnerabilities. A total of US$75,000 (S$130,332) was paid out in rewards to hackers.

That programme was later expanded to cover measures such as a vulnerability-disclosure policy for the department, allowing hackers to report cyber loopholes.

More than 2,800 vulnerabilities have since been resolved through these disclosures — of which over 100 were of “high or critical severity”, including Structured Query Language injections (attacks that could result in data being stolen) and ways to bypass authentication, HackerOne said on its website.

Calling cyberspace a “new battlefront”, Mindef said Singapore was exposed constantly to the rising risk of cyber attacks, and the ministry was an attractive target for malicious activity.

Mr Koh noted the challenging landscape, where new malicious attacks are launched daily on both government and private systems. “Some people have gone so far as to say that the next major conflict will see cyber activity as the first activity of a major conflict between countries,” he said.

The new initiative will allow Mindef to tap crowdsourcing to detect vulnerabilities, on top of the work done by its existing teams, said Mr Koh. “No individual organisation, not even the Government, has enough resources to check our own networks and systems, and fix all the vulnerabilities, all the time,” he added.

In February, Mindef was dealt its first cyber-security breach when the personal details of 850 national servicemen and staff were stolen in a cyber attack.

The breach of Mindef’s internal I-net system, which gives national servicemen and employees Internet access for their personal communication and web surfing, was executed remotely over the Internet. No classified military data was lost but, as a precaution, Mindef checked all its other computer systems in the aftermath of the breach.