Nostalgia: A force for good, but a double-edged sword?

SINGAPORE — One expert calls it the “sweet imagination of the past when the present is found wanting”, while others describe it as a “warm fuzzy feeling” or a “hipster heritage impulse”.

SINGAPORE — One expert calls it the “sweet imagination of the past when the present is found wanting”, while others describe it as a “warm fuzzy feeling” or a “hipster heritage impulse”.

Whatever one calls the wave of nostalgia that has swept across the island, this phenomenon, which has been accentuated by the social media explosion, is unlikely to go away any time soon. And there are implications for policymakers beyond the clamour for buildings and areas to be preserved, such as the rise of socio-cultural clashes, the experts noted.

“Nostalgia is the gentle narcotic for a bruised soul. It can be canned and sold. Look at the National Museum’s replicating of childhood games — there is an audience and market for it,” said Dr Terence Chong, a senior fellow at the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. “There is a fetish for nostalgia out there.”

Dr Thum Ping Tjin, a research fellow at the National University of Singapore’s (NUS) Asia Research Institute, attributed it to the renaissance of civil society here. “We are both looking back to our accomplishments of the past, and forward to a brighter, more inclusive and participatory future,” he said.

While historians, sociologists and other experts generally welcomed nostalgia as a force for good, some warned that it could be a double-edged sword.

“It can turn ugly when it feeds into the idea that there is an authentic Singapore, which can become fodder for xenophobia,” said Singapore University of Technology and Design lecturer Nazry Bahrawi, who conducts research into culture and urbanisation, among other fields.

There is also the human tendency to view the past through rose-tinted glasses, Mr Wan Wee Pin, the National Library Board’s deputy director of engagement, pointed out.

“It is a fallacy to think of nostalgia as only the good old days,” he said. “We have heard people talk about the ‘kampung spirit’ and the close community then, but honestly, would you want to live in a kampung today?”

S’pore’s swift development seen as driving force

The rapid pace of change — in terms of both the physical landscape and the cultural milieu — that Singapore has undergone since its independence 49 years ago is the main driving force behind the longing for the good old days, the experts said.

Dr Chong said: “Nostalgia is the sweet imagination of the past when the present is found wanting. The influx of foreigners and the unrelenting urban development mean we are changing in a stream of change, which can be discomforting and disorientating.”

Dr Chua Ai Lin, an NUS historian who is also the president of the Singapore Heritage Society, noted that Singaporeans have been “unable to catch up with their country’s development”.

“Singapore changes especially fast. This has resulted in gentrification, or the neighbourhood being displaced by new users,” she said.

Assistant Professor Loh Kah Seng, who teaches the history of Singapore and South-east Asia at Sogang University’s Institute for East Asian Studies, noted the desire of Singaporeans to lead a “simpler, less hectic, less constrained life”.

“Nostalgia is a critique of the changes that have taken place in Singapore in the opposite direction. Now (we experience) greater stress, less autonomy, more complicated life choices, et cetera,” he said.

Several experts, including Asst Prof Loh, see the outpouring of nostalgia as an avenue for young Singaporeans to express their idealism and aspirations.

For older Singaporeans, it could be a longing for the days when Singapore was an open society with a thriving civil society, said Dr Thum.

Dr Nazry sees it somewhat differently. What the youth in particular are experiencing is a “hipster heritage impulse” — a form of nostalgia that appeals specifically to middle-class young, urban professionals who pick certain aspects to reminisce about.

“It romanticises the idea of an idyllic Singapore past that must be preserved,” he said, pointing to the mushrooming of “folkish but fashionable cafes, bookstores and other entrepreneurial ventures”.

Referring to the internationally acclaimed film Ilo Ilo, which was made by homegrown director Anthony Chen and depicts the relationship between a family and their maid in Singapore during the 1997 Asian financial crisis, Dr Nazry said: “Our best-known cultural product ... is shaped by this nostalgic impulse. I see this as a sign that young affluent Singaporeans are rebelling against years and years of thinking along the lines of economic pragmatism; that they are embracing a post-pragmatic Singapore.”

Rethinking nationalism

From the plethora of blogs reminiscing about the past — many set up by individuals or groups documenting and preserving the heritage of various places — to the creation of numerous heritage trails and the strong public reaction to redevelopment projects, the wave of nostalgia here is evident.

The Singapore Memory Project, a government-initiated national movement, has also garnered enthusiastic response from the public, for example. Events and activities organised by the Singapore Heritage Society have also seen growing interest, especially among the youth.

While experts said the trend could lead to Singaporeans being more informed and aware of the country’s past — and ultimately, a more mature polity — Dr Chua drew a distinction between interest in the Republic’s more recent past and a deeper appreciation and understanding of its history.

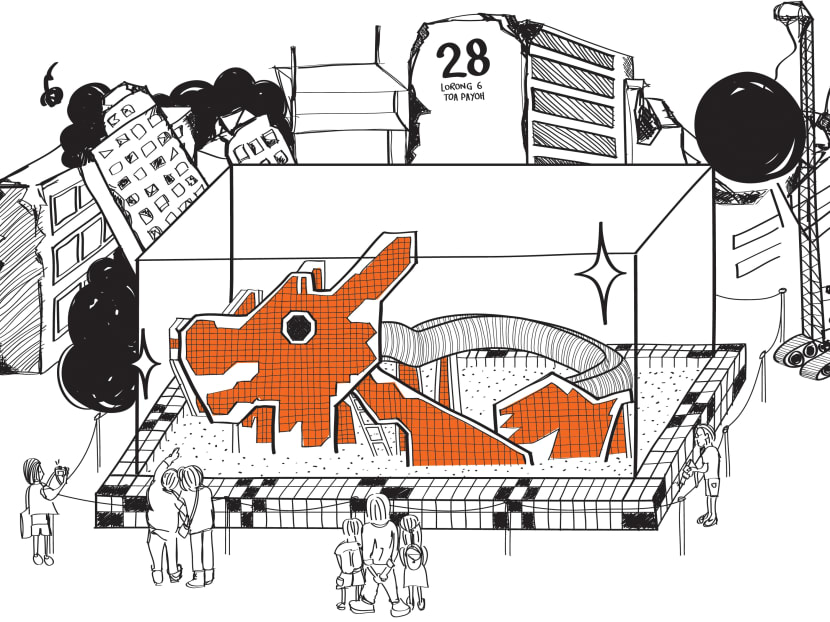

“Speaking as a historian, there has been stronger support for heritage of the past few years. People reminiscing about old Housing and Development Board (flats), playgrounds, kopitiams,” said Dr Chua.

“However, a very important part of Singapore’s history has been overlooked. What was Singapore like 700 years ago? There is a danger of Singaporeans being too focused on the recent past and not the deeper past.”

Still, NUS sociologist Tan Ern Ser said nostalgia could strengthen national identity and bonds among people. “It is about collective identity, sense of belonging, pride, values, and priorities for the future. For quite a while, Singapore was experienced more as an economy, rather than a nation. There is now greater identity and pride.”

Mr Wan agreed, citing the Singapore Memory Project as an example of strangers coming together to make connections.

“Nostalgia is good when you look back and realise that there are things that have defined and contributed to who you are and, as a result, you make a connection with the people who have the same experience,” he said.

However, too much of a good thing can be unhealthy. If people hang on to the past too much, “you are longing for things that no longer exist and therefore you face a struggle”, Mr Wan noted.

Dr Nazry also warned about the potential pitfalls of nationalistic fervour, when Singaporeans start feeling entitled “to a land of one’s own, and worse, a sense of purity”.

He said: “I believe Singaporeans need to rethink their attitudes towards nationalism. We talk about national identity as if it is a sacred, pure thing, but forget that there is an ugly side to it.”

‘Consider symbolic, historical value of policies at the start’

On the implications for policymaking, Dr Nazry said: “At a benign level, we will probably see greater pressure for the Government to preserve cultural heritage.”

But things can get less benevolent when it comes to symbols of cultural heritage, such as the notion of a traditional family, he said. “Policymakers would do better to anticipate points of sociocultural conflict, rather than react to them.”

Dr Chong felt that policymakers may adopt two possible approaches to nostalgia. One, they could dismiss it as “irrational, sentimental or mawkish”, in favour of pragmatism and “developmental rationalism”.

The consequence would be a hardening of views from the public and the Government, increasing the sense of frustration among those who are attached to heritage, Dr Chong said. Two, the Government may point to buildings and sites that have been preserved as “concessions to heritage”.

“The politics of multiculturalism will come into play ... the balancing act between different (types of) cultural heritage will be deployed as an ideological and policy consideration,” he said.

Dr Chong predicts a “museumification of heritage and history” here. “By this, I mean we set aside a few historical sites, gazette them or stare at precious artefacts behind glass cases. We will be a country with token heritage ... enough heritage to show outsiders, but not enough to feel this is our home.”

Dr Chua noted that heritage sites such as the old Bidadari Cemetery are “more like a museum”. “It is aesthetically beautiful, but not a leap (at the) holistic level,” she said. “When policies are made for the development of infrastructure, they need to take into consideration data that is holistic, meaning historical, social and political.”

Right now, many policies are made without heritage assessment, she said, noting that it is harder to change the policies given that the planning for the country’s development was done decades in advance.

She added: “It is really about engaging the people and keeping them well informed (through the process).”

Steps are being taken in this direction. Last year, as a nod to rising civic activism, the National Heritage Board formed an impact assessment and mitigation division to study the effect that development has on Singapore’s heritage.

Dr Tan said policymakers should consider the symbolic and historical value of their policies, right at the start, “not just simple costs and benefits in monetary terms”.

“The fact that we have a rather interventionist Government means that so much of what we see in Singapore has, to a large degree, been the product or by-product of government policy and action,” he said.

Read more stories in our National Day Special:

- Longing for the good old days

- Preserving memories of a changing nation

- Nostalgia: A force for good, but a double-edged sword?

- Tiong Bahru: A hip and miss affair

- Shops, museums in Katong seek to preserve Peranakan culture

- Town of firsts contemplates modernity

- Balestier’s vintage shops hold on to fading trade

- Heritage buildings given new lease of life

- Newer structures shaping Singapore’s identity too

- Old brands, new strategies

- Businesses stay loyal to their roots

- Singapore’s sporting greats

- Sports: Young guns make their mark

- Sports: It’s all in the delivery

- The A to Z of S’pore’s arts and entertainment scene

- The future of S’pore’s arts and entertainment scene

- #TODAYremembers: An interactive map featuring our readers' favourite memories about Singapore