Reserved presidential election casts spotlight on ‘Malayness’

SINGAPORE — The issue of whether a presidential hopeful is “Malay enough” to contest in the coming presidential election reserved for Malays has come into sharp focus in recent weeks.

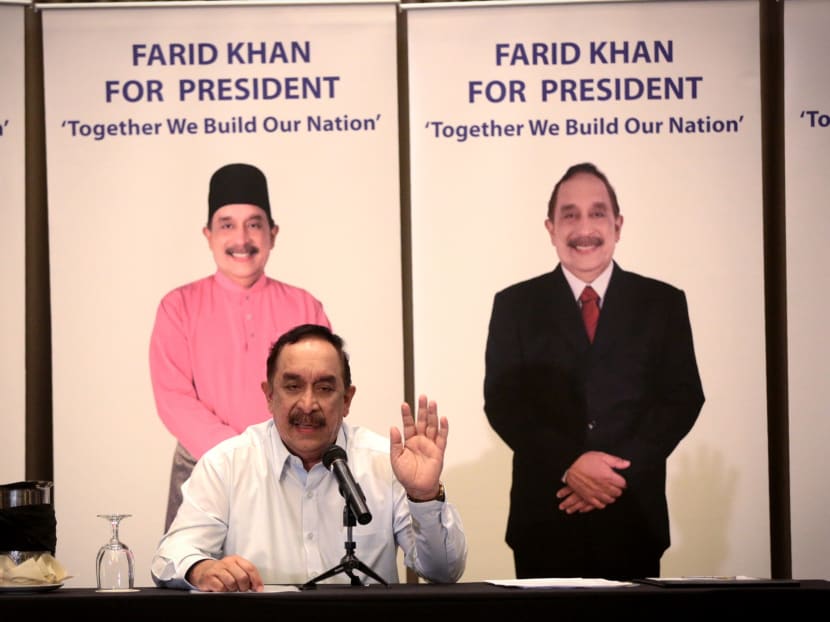

Presidential hopeful Farid Khan Kaim Khan. Mr Khan, whose race is indicated as “Pakistani” on his identity card, had to fend questions about his “Malayness” when he announced his intention to run for president. TODAY file photo

SINGAPORE — The issue of whether a presidential hopeful is “Malay enough” to contest in the coming presidential election reserved for Malays has come into sharp focus in recent weeks.

While the topic has stirred much public discussion, Malay community leaders whom TODAY spoke to felt that the definition for the purpose of the election should be inclusive and not too narrow, given Singapore’s multi-racialism and multi-culturalism. “Even though the person may not be 100 per cent Malay but practises its culture, mixes with members of the community and so on, should the person be considered a Malay? Or you want to say, no, and then divide the community further?” said Mr Othman Haron Eusofe, a former Member of Parliament.

Political analysts also felt that voters should not be overly-fixated with a candidate’s ethnicity – albeit being an election reserved for a particular race – as it would “detract from the raison d’être of the elected presidency and of the elected president as a symbol of our multiracialism”, as Singapore Management University law don Eugene Tan put it.

Last week, Mr Farid Khan Kaim Khan, 62, chairman of marine service provider Bourbon Offshore Asia Pacific, declared his intention to run in the polls, about a month after Second Chance Properties CEO Salleh Marican had thrown his hat into the ring.

Mr Khan, whose race is indicated as “Pakistani” on his identity card, had to fend questions about his “Malayness” at the press conference to announce his intent while Mr Marican, 67 – who is of Indian heritage – has been heavily criticised for his lack of fluency in the Malay language.

Another name that has been floated as a potential candidate is Speaker of Parliament Halimah Yacob, whose father was Indian-Muslim.

To qualify for the reserved election in September, prospective candidates will have to submit a community declaration to the Community Committee to certify their ethnic group. A fact-finding process will be conducted by the Malay community sub-committee to decide if the candidate belongs to the community. The person may be interviewed and required to provide further information, among other things.

The sub-committee is chaired by former Nominated Member of Parliament (NMP) Imram Mohamed. Other members are Singapore Muslim Women’s Association adviser Fatimah Azimullah, Islamic Religious Council of Singapore president Mohammad Alami Musa, former senior parliamentary secretary Yatiman Yusof, and former NMP Zulkifli Baharudin.

Speaking to TODAY, Mr Yatiman said the sub-committee will make its evaluation based on Article 19B of Singapore’s Constitution. The provision states that a “person belonging to the Malay community” means any person, whether of the Malay race or otherwise, who considers himself to be a member of the Malay community and who is generally accepted as a member of the Malay community by that community.

‘INCLUSIVE’ POSITION IN THE CONSTITUTION

Both Mr Yatiman and Mr Othman pointed out that the definition of a Malay in the Singapore Constitution is different from Article 160 of Malaysia’s Constitution which stipulates that a person has to satisfy two sets of requirements in order to be recognised as a Malay: He or she has to profess the religion of Islam, habitually speaks the Malay language, and conforms to Malay custom. The person also has to be born in the Malaysian Federation or in Singapore before Merdeka Day – which fell on August 31, 1957 – or has links to the Federation or Singapore.

Mr Othman, who was an MP from 1980 to 2006, noted that the definition of a Malay in Singapore’s Constitution is “inclusive in nature”. The evaluation of whether a presidential candidate is recognised as a member of a particular race is identical to the assessment for minority candidates under the Group Representation Constituency system in the General Elections (GEs)

Mr Othman noted that the issue of “Malayness” has not cropped up during past GEs. “I supposed that it’s more pronounced now because some in the community might feel that if the highest office of the land should be occupied by a Malay, the person should be 100-per-cent Malay,” he said.

Malay-Muslim self-help group Yayasan Mendaki has a set of criteria for its financial assistance schemes for students administered on behalf of the Government. Among other things, the recipients “must be of Malay descent” as stated in their identity cards. It spells out a list of what it considers to be “Malay descent”, and this includes 22 ethnicities including Acehnese, Javanese, Boyanese, Sumatran, Sundanese and Bugis. Students with “double-barrelled” race are eligible if the first race is listed on the identity cards as Malay, said a Mendaki spokesman. For example, a student who is Malay-Arab would qualify for the schemes but an Arab-Malay student would not, he added.

However, for the Presidential Election, Association of Muslim Professionals chairman Abdul Hamid Abdullah stressed the need for a “wider definition of a Malay” in Singapore’s context. A narrow definition would be restrictive and could disqualify potential candidates who have been “accepted” as a member of the Malay community, he added. “It is better to be inclusive. Otherwise, (it) may lead to divisiveness in the Malay community,” he said.

SCRUTINY ON ETHNICITY INEVITABLE: ANALYSTS

The political analysts noted that the scrutiny on the ethnicity of prospective candidates would similarly occur when it comes to the subsequent reserved Presidential Elections for different races.

Nevertheless, Assoc Prof Tan said the issue has raised some questions: “But what is meant by Malayness? Is it race, language, religion, culture? When does a non-Malay ‘become a Malay’? Or when is a classified Malay not Malay enough?”

If anything, the reserved election has sparked a renewed discussion on race, said Dr Mustafa Izzuddin, a fellow from research centre ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute. The “conundrum” right now, he added, is whether the reserved election is “solely for the Malays or can be broadened to consider both Malays and Muslims who consider themselves Malays”.

“This has and will divide opinion within the Malay community as the reserved presidency plays out further in the coming weeks,” said Dr Mustafa.

Assoc Prof Tan said the reserved election “inevitably puts race up front and centre”. However, it is “imperative that we do not get too hung up over the race” of a presidential hopeful, he said.

After all, Dr Mustafa pointed out: “The beauty and strength of the Malay race has always been its unity in diversity with regard to customs, practices and everyday living. The kinship ties between the various communities in different countries, particularly in the Southeast Asian region known as the Nusantara, is what defines Malay as a collective ethnic group.”