Rewriting how logistics is done

SINGAPORE — When Mr Lai Chang Wen, co-founder of men’s apparel retailer Marcella, realised that deliveries of his shirts were either getting lost or not arriving on time, he became increasingly frustrated.

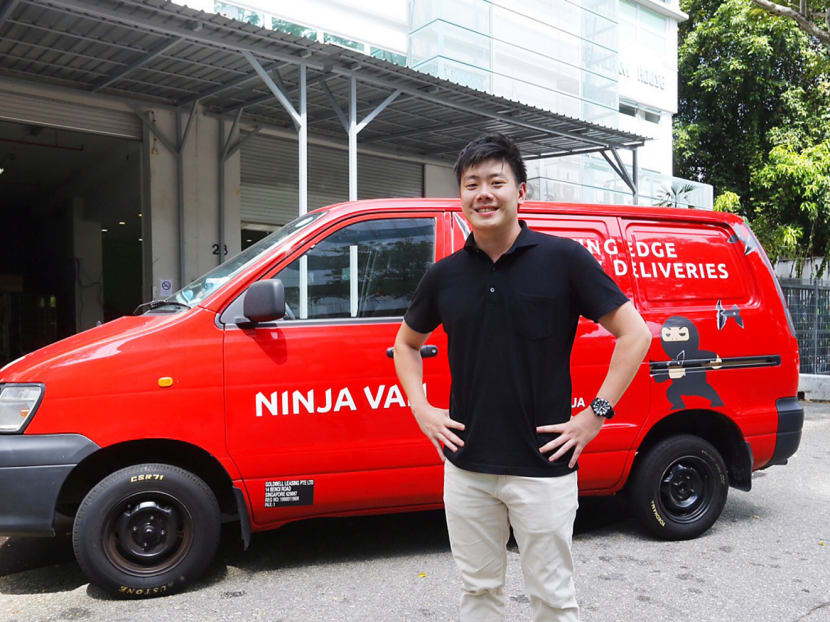

Mr Lai Chang Wen, CEO of Ninja Van, which specialises in next-day delivery for e-commerce companies. Photo: Ernest Chua

SINGAPORE — When Mr Lai Chang Wen, co-founder of men’s apparel retailer Marcella, realised that deliveries of his shirts were either getting lost or not arriving on time, he became increasingly frustrated.

The more he looked into the courier that was delivering his customer orders, the more he realised that the “old school” logistics industry had a “very big problem”, in that they did not look at the big picture when taking up delivery contracts. “The way they bid for it (a contract), they don’t look at how this synergises with a lot of their operations,” the 28-year-old explained.

This “siloed” outlook led to inefficient methods of delivery, he added. For example, some operators could not make punctual deliveries because the location of their jobs did not allow them to plot an optimal route.

To overcome this, Mr Lai and his partner at Marcella, together with a team of software engineers, used technology to rewrite how logistics is done.

Launched in April last year, Ninja Van is a logistics provider that serves more than 300 merchants, including health and beauty retailers Watsons and Guardian, and e-commerce companies such as cosmetics retailer Luxola and electronics retailer Lazada.

Mr Lai said his start-up, which also operates in Malaysia, does about 5,000 deliveries a day, making it the second-largest logistics provider here. He said the largest, Singapore Post, makes about 10,000 deliveries a day.

Ninja Van’s growth can be attributed to its use of technology-driven logistics, which allow deliveries to be made more cheaply and efficiently. This involves the use of algorithms that decide specific details, such as which vehicle should be used to deliver a parcel or which route an operator should take. As a result, drivers are able to deliver more parcels in an hour, while saving on fuel costs.

In addition, Ninja Van, which has about 200 employees, works with other logistics providers to increase its delivery capacity when needed. For example, it offloads deliveries to McDelivery — the McDonald’s service that delivers food to customers’ doors — when the latter experiences a lull in operations. “But our systems control them, so we have full traceability,” Mr Lai said.

Partners that pay for this arrangement can tap Ninja Van’s technological infrastructure to optimise their own deliveries. In addition, they can employ Ninja Van’s fleet to help with their operations.

One challenge, Mr Lai said, is to pair technology with logistics. “To quantify them (realities) and push them into your algorithms, for them to work as an entity, that’s where this gets very interesting,” he said. And, some drivers, when delivering parcels, show a preference for certain locations or travelling by routes they are familiar with.

Although faced with this difficulty, coupled with high Certificate of Entitlement and fuel prices at the time of starting his logistics business, the Singapore Management University graduate in finance took the risks in stride.

“I decided that if you want to try your own thing, you try it early. You don’t have a family and all, so you can still afford to take that kind of risk,” said Mr Lai, who is still single. “Sometimes, things just happen and you roll with the punches.”