Singapore needs a health sciences university to fill current void: Professor

SINGAPORE — Calling for a biomedical university to be set up here, the senior vice-dean of Duke-NUS Medical School said that the role of the medical school needs to be expanded, as students should be trained in higher medical education in Singapore itself instead of heading to other countries.

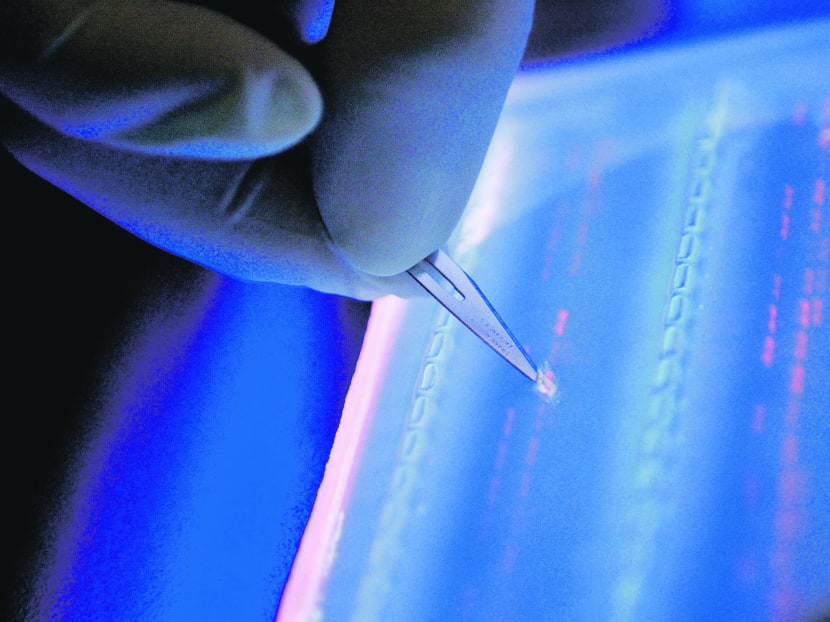

A lab officer cuts a DNA fragment under UV light from an agarose gel for DNA sequencing as part of research to determine genetic mutation in a blood cancer patient in Singapore. AP file photo

SINGAPORE — Calling for a biomedical university to be set up here, the senior vice-dean of Duke-NUS Medical School said that the role of the medical school needs to be expanded, as students should be trained in higher medical education in Singapore itself instead of heading to other countries.

Speaking at the SingHealth Duke-NUS Scientific Congress 2016 on Friday (Sept 23), Professor Soo Khee Chee said that there is a “grand vision” of wanting “more than just a medical school” in this country.

It disconcerted him that “there was not sufficient consideration given to proper education”, after engaging with young Singaporeans who were doing higher education in healthcare in Australia. The students also told him of the difficulties in finding appropriate postings — or there was a lack of postings — as well as issues with housemenship admissions when they graduated.

“The question that I have is, can we really entrust the future of our healthcare training to other countries?” Prof Soo asked.

“Should we now consider therefore an expanded role for Duke-NUS Singhealth partnership in this particular campus? ... This is what we think we should move to, a biomedical university, totally relevant, totally serving the needs of the country.”

A biomedical university, or health sciences university, he said, may include courses such as health management (hospital governance and medical logistics), health economics (intellectual property, medico-legal issues), and even the area of clinical trials. Medical specialities such as public health, dentistry, nursing and physiotherapy may also be offered.

Prof Soo, who is senior vice-dean of clinical, faculty and academic affairs at Duke-NUS Medical School, said there are many reasons for establishing such a university in Singapore instead of relying on overseas education. For one, quality of training and values of healthcare are assured, with Singapore needing students to be “pairs of hands” in the healthcare system.

Innovations in healthcare and research could also be developed and, with that, implementation is best done within the system, and a stronger medical and academic community would result.

The Health Ministry could support this venture, quipped Prof Soo to Health Minister Gan Kim Yong, who was guest of honour at the congress. To that, Mr Gan said: “I do hear your appeal and request, and we’ll certainly give it serious consideration.”

However, Mr Gan said that this has to be “taken in the context of the national agenda (and) mission, and needs to be aligned with our programme and strategy for developing our education and research sector”.

At the opening ceremony of the two-day congress, Mr Gan talked about a couple of new and ongoing research projects, highlighting that meaningful research and education would be important as the population ages and there is a higher burden of disease.

In one new research study looking at heart disease, a genomic and clinical database of heart disease patients and healthy individuals — 20,000 people combined — will be built.

“By studying the two cohorts’ genetic risk factors and clinical characteristics, researchers hope to understand the genetic and clinical markers that may predict an individual’s risk of developing heart disease,” Mr Gan said.

In another project, the Singapore General Hospital (SGH) tried out a new model of care that aimed to improve care for patients during and after their hospital stay. For the trial, 1,600 high-risk patients took part — half of them were put on this new model, the other half on the usual discharge programme.

Associate Professor Lee Kheng Hock, a senior consultant in family medicine and continuing care at SGH, said: “We would visit them in their wards, make sure we understand their condition, what they do when they leave the hospital. When they leave, we would make sure that they have all the access to all the people who could help them.”

Results showed that for the group under the new care model, there was a 20- to 30-per-cent reduction in the length of the hospital stay and hospital re-admission risk, compared to the group in the current programme.

The project will soon be expanded to include 5,000 high-risk patients. One is assessed to be high-risk by factors such as the nature of the disease, the length of stay of their previous admission, and the number of previous emergency visits.