Singaporean cooking instructor wants to save heritage 'kueh' by getting you to make it at home

SINGAPORE — Move over, burnt cheesecake. It's time for kueh.

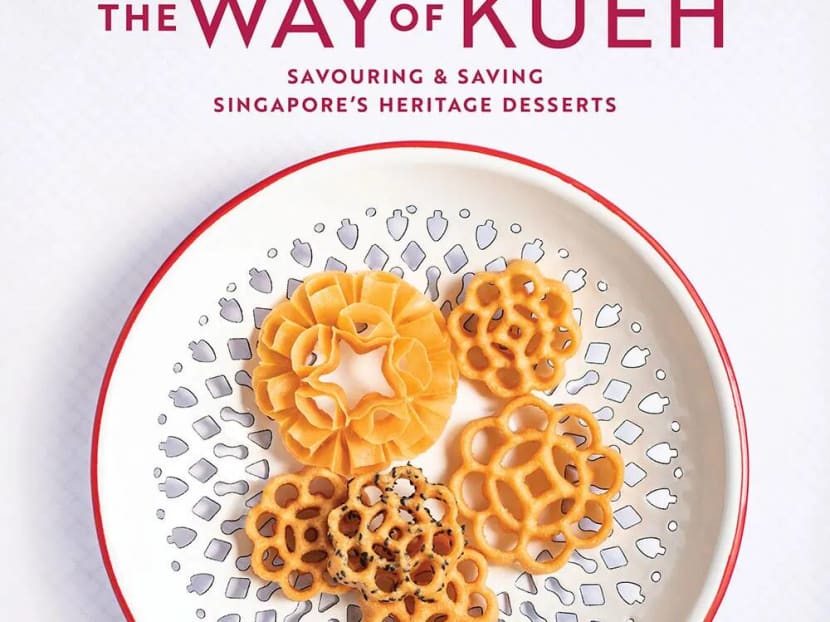

Mr Christopher Tan's latest cookbook The Way of Kueh hopes to start a "kueh-naissance" where everyone will be inspired and encouraged to make and enjoy kueh together.

SINGAPORE — Move over, burnt cheesecake. It's time for kueh.

Singaporean writer and cooking instructor Christopher Tan wants more people to appreciate heritage kueh before it vanishes.

Often overlooked for trendier or Instagram-worthy eats, kueh's existence is slowly disappearing from many people's daily lives.

Many are also settling for sub-standard commercially-made kueh out of convenience and forgetting the traditional taste of kueh as time goes by.

"It is imperative that we record, preserve and continue to cook our traditional kueh recipes, or we may risk losing them for good, along with the rich culture surrounding them," said Mr Tan.

His latest cookbook The Way of Kueh hopes to start a "kueh-naissance" where everyone will be inspired and encouraged to make and enjoy kueh together, in an effort to preserve this important part of Singapore's food heritage.

The book showcases 98 kueh recipes from Singapore's Malay, Chinese, Peranakan and Eurasian communities.

The recipes are detailed and accompanied by stunning photographs including step-by-step pictures which were composed, styled and shot by Mr Tan.

The book can be thought of as a kueh encyclopedia which also documents kueh's history, regional connections and colonial influences through essays and interviews with artisans who make kueh.

Growing up in a Peranakan family, Mr Tan was always surrounded by kueh — especially during festivals.

He recalled, "I fondly remember helping my grandma 'cubit' kueh bangket for Chinese New Year."

As his family was obsessed with food (Mr Tan's father is Mr Terry Tan who also writes cookbooks), he admitted to developing "a deeper sensitivity and openness towards all kinds of cuisine, and to the importance of heritage."

As a long-time volunteer for Slow Food Singapore — a movement that sets out to preserve and celebrate all aspects of traditional food culture — he got involved in an event called Kueh Appreciation Day.

The event, held yearly since 2015, brought together small heritage kueh businesses to sell their kueh and educate the public about kueh heritage.

It also became the catalyst for him to write the cookbook. "It was witnessing the changing relationships between kueh, kueh-makers and kueh consumers at these events that also drove me to write The Way of Kueh.

"I saw a lot of people — both young and middle-aged — who were unfamiliar with kuehs from their own heritage, who were nonetheless keen to try kuehs and find out more," he said.

With over 20 years of food writing and culinary teaching under his belt, Mr Tan was the right person for this mammoth task.

He had already written and co-written many cookbooks, with The Way of Kueh being his 13th one.

In 2017, Mr Tan received a Heritage Project Grant from the National Heritage Board that helped propel the making of the cookbook.

No shortcuts were taken by Mr Tan with the recipes in the cookbook. Most of them were researched and forged from scratch.

Some, like the pineapple tarts, were from family recipes. "While I interviewed over 40 kueh-makers for the profiles in the book, I only asked them to share their memories, stories and opinions: I specifically did not ask any of them to share their recipes, as I believe that family recipes are intellectual property, and I wanted to respect that."

His research saw him comparing and analysing different versions of each recipe, with some requiring translations from their original language.

His resources included libraries and antique books. "Using my knowledge of kueh and my taste memories, I then created my own version of each kueh from scratch, trying my best to capture what I understood to be the traditional flavour and texture of each item."

Each recipe was tested between four to 20 times to refine the kueh to Mr Tan's satisfaction.

True to the adage that the simplest things are the hardest, it was the simplest kueh recipes that required more work.

He explained, "When there are only a few ingredients, their ratios and the cooking techniques must be more precise in order to showcase the personality of the kueh."

In keeping the kueh as real as possible, Mr Tan tested them in his home kitchen. Even the photographs were all shot in Mr Tan's home

"It was important for me to make the kuehs look not just attractive but achievable in the photos — not like they were slaved over by an army of professional chefs, but like the true home-heritage recipes that they are."

For the recipes, a more practical approach was adopted by Mr Tan. He omitted some traditional methods that wouldn't work today, like stone-grinding your own rice flour.

"My goal is to encourage people to start making kueh at home again, and hence my recipes freely use modern kitchen tools like stand mixers and electric ovens."

He only recommends traditional equipment such as a putu mayam press, if it is irreplaceable or offers better results. For some recipes, he made some changes, like reducing the amount of sugar to make the kueh taste less cloying.

He also used all-natural colouring and flavouring ingredients rather than artificial additives. In addition, the book includes four recipes that show how innovation and modern twists can be applied to kueh.

One may ask whether these recipes are "authentic" since every family has its own approach to making kueh. Mr Tan's opinion is that a recipe can only be authentic to something, like a time, place, country, clan, family or person.

He explained: "How my family makes a particular kueh may be different from how your family makes it but each version is authentic to each family."

In working on these recipes to showcase heritage kueh, Mr Tan adopted the policy that one must consider how an entire community approaches traditional dishes to understand why those recipes are special to that community.

"There is never just a single recipe for anything, but rather a spectrum of recipes which all together, in unison, constitute an 'authentic' portrait of that dish."

With The Way of Kueh and the slow disappearance of kueh culture, Mr Tan hopes that people will understand what goes into making good kueh and support those who still uphold the traditional, laborious methods of kueh-making.

Moreover, he believes that the the family bonding aspect of making kueh during festivals, weddings and special occasions also needs to be revived, as it is essential to many Asian cultures. MALAY MAIL