The Big Read: Who’s on the frontlines of conservation? A bunch of (expert) amateurs ...

SINGAPORE — Whom might you turn to for help to identify a rare spider, stick insect or butterfly in Singapore? Try a retired diplomat, a colorectal surgeon and an architect, respectively.

SINGAPORE — Whom might you turn to for help to identify a rare spider, stick insect or butterfly in Singapore? Try a retired diplomat, a colorectal surgeon and an architect, respectively.

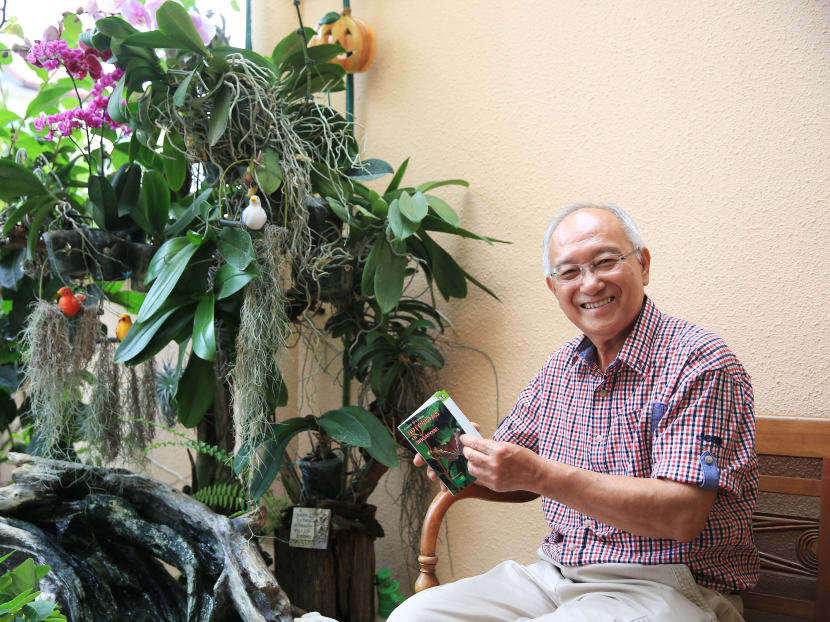

Mr Joseph Koh, Dr Francis Seow-Choen and Mr Khew Sin Khoon are part of a small but valuable pool of “amateur experts” on various creatures in the animal kingdom here. Over the decades, they have happily contributed to science by pursuing their interests to what fellow hobbyists might consider dizzying heights.

Despite their amateur status, their contributions and expertise arguably have never been more important, with environmental conservation regularly coming to the fore in public debate here, most recently in the development of the future Cross Island MRT line (CRL) and its possible impact on the Central Catchment Nature Reserve, and threats to biodiversity worldwide.

For instance, Mr Koh, an authority on spiders in Singapore, is part of the working group in talks with the Land Transport Authority on the CRL.

Some also help in biodiversity surveys spearheaded by the National Parks Board (NParks) — Dr Seow-Choen, Mr Koh, Mr Khew and Nature Society Singapore Bird Group’s Alan Owyong are involved in a survey at Bukit Timah Nature Reserve and the Ecolink@BKE.

Many amateur naturalists are able to spend more hours in the field than some specialists, and thus represent the frontlines of nature study and documentation, said NSS president Shawn Lum.

There are very few professional biologists and ecologists active in the NSS, whose ranks include many of Singapore’s most respected amateur experts, said Dr Lum, a lecturer and tropical forest ecologist.

“A number of the amateur naturalists are as technically capable as professional botanists or zoologists in some aspects of the field, and they invariably have an enthusiasm and love for nature — and a willingness to speak up and to be counted — in a way that is arguably more muted among the professionals,” he said.

Except for Mr Koh, who studied zoology at university before entering the civil service, the amateur experts had no formal training in biology or zoology, and do not make a living in the field. Many of them simply followed their natural curiosity piqued from a young age.

For instance, Mr Khew, the chief executive officer of CPG Corporation, which does building consultancy and facilities management, fell in love with butterflies when he was growing up in Malaysia. A pioneer of the ButterflyCircle, a group of enthusiasts and hobbyist photographers, he authored the Field Guide to the Butterflies of Singapore, published in 2010.

Birder Lim Kim Seng, 56, had nature at his doorstep growing up on a family farm in Sembawang. He developed an interest in birds because he found them easier to observe and identify than other groups of animals or plants. However, he made little headway before he joined the then Malayan Nature Society at the age of 15.

With a background in mechanical engineering, he spent 25 years in the manufacturing sector before going for his Master of Science in Environmental Management, and is now a part-time lecturer and full-time nature guide. What stayed constant was the devotion to his interest: He penned books on birds, participated in research and helped in the development of NSS’ Birds of Singapore app, driven by passion, a thirst for knowledge and the desire to make things easier for others wanting to learn more.

“After (some) time, you find you’ve reached that point: What should I do? Maybe what I need to do is to document all this information somewhere that can benefit other people, because I had a hard time picking it up. In the future, it shouldn’t be so difficult. I think that was what drove me,” said Mr Lim. His first book, in 1992, was on the vanishing birds of Singapore; he wrote field guides in 1997 and 2010, and two more books in 2009.

MADNESS THAT BENEFITS SCIENCE

Some of the amateur experts, such as Mr Lim and fellow birder Professor Ng Soon Chye, firmly reject the label of “expert” or “authority”.

“Please specify I’m not an expert, I don’t want to go under false pretenses,” said Prof Ng, a gynaecologist and one of the men behind Asia’s first test-tube baby in 1983. “Maybe I know more than the general public but that’s about that ... It’s (the) small efforts by everybody that make a movement,” said Prof Ng, 66, who has published scientific papers on birds.

Professor Peter Ng, head of the Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum at the National University of Singapore, calls them “professional amateurs”. They may know less about the rules and procedures of taxonomy — the science of naming, describing and classifying organisms — than full-time scientists like himself. And in their obsession with a particular kind of creature, they are different from naturalists with their broad knowledge of conservation and the environment, he said. “It’s the intensity and purpose that’s different.”

Many of the amateur experts here have built distinguished careers, but have brought similar levels of energy and professionalism to their hobby. “They’ve taken their hobby to another level, and that level makes them pretty good scientists,” said Prof Peter Ng, whose museum works with many of these individuals and has appointed some as honorary research affiliates.

The Natural History Museum nurtures their hobbies. The amateur experts might need references or specimens from other countries that they cannot get as private individuals. Or they might need tools such as microscopes or cameras.

Does the presence and relative prominence of these professional amateurs mean that the pool of biologists and zoologists here is very small? Every natural history museum has limitations in size and budget, said Prof Peter Ng. “Some people say a museum or university should have experts on every group of animals. Impossible! Why? There are too many kinds of animals, and despite what some people may claim, it’s impossible to be an expert on everything,” he said.

“You’re talking about millions of species of animals. To know one group very well requires lots of energy and time. Even the largest museums in the world can’t afford this luxury.”

Working with the amateur experts allows the museum to augment its pool of experts “straightaway”.

“And the nice thing is, we don’t have to pay them — I always call them free labour,” quipped Prof Peter Ng. “I always say all of us are crazy; our madness bonds us.”

NO REGRETS OVER PATHS TAKEN

So why didn’t the amateur experts pursue their interests as a career? Pragmatic parents and a relative lack of opportunities and jobs available in biology and zoology were among the reasons cited. But they expressed few, if any, regrets about their choices.

Spider expert Mr Koh said he simply followed his heart after graduation in 1972 and applied for a position at the Singapore Administrative Service. It was “a calling that had eclipsed my passion for spiders”, but it did not mean giving up arachnology, he said.

“At a time when ensuring the survival and prosperity of Singapore was our national preoccupation, the Singapore Armed Forces and the civil service were powerful magnets for many young people looking for purpose and meaning in life,” said Mr Koh.

The National Parks Board (NParks) is another institution that benefits from collaborating with amateur experts, who help identify species and verify the number of species in various areas. With deep knowledge in specific taxa, the amateur experts provide NParks with advice on enhancing parks or roadside greenery to make them more conducive to biodiversity, said Dr Lena Chan, group director of NParks’ National Biodiversity Centre. “They are reliable sources of detailed data as they have accumulated many years of experience.”

Besides equipment, NParks supplies resources from the Singapore Botanic Gardens Herbarium and Library, and it facilitates access permits for the amateur experts.

The National Biodiversity Centre also has two schemes to support individuals in their research: The Honorary Research Associate Scheme and, for emerging researchers and enthusiasts, the Research Fellowship Scheme.

The nature community is confident of a younger generation ready to take over the reins in due time. Young naturalists are making good contributions to groups of animals that the public is less aware of, such as dragonflies, lady beetles, bees, ants and various marine organisms, said Dr Lum.

Prof Peter Ng would not predict who among the younger ones could follow in the footsteps of today’s amateur experts. Those in their 20s and 30s would be in the midst of developing their careers and families, and their fascination would develop along the way, he said. “I think we’ll probably see them blossoming when they’re in their 50s … But I can predict there will be a lot more.”