US bases, other sore points fuel support for Okinawan independence

NAHA (OKINAWA) — In a decrepit office below a billiard hall in the city of Naha, the capital of Okinawa in southern Japan, a small group is dreaming of a new country.

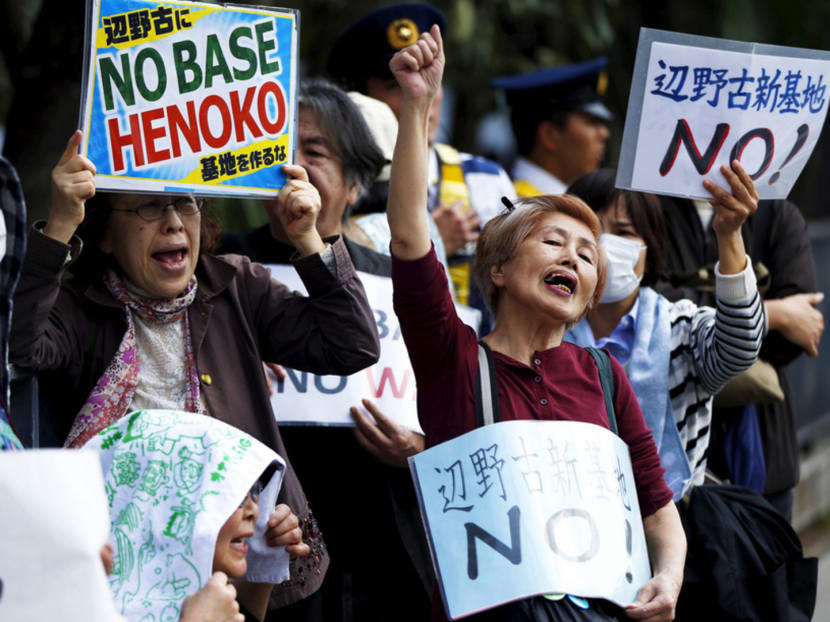

Residents protesting the planned relocation of a US military base to Okinawa’s Henoko Bay. Resentment over the bases has led to an increasingly loud call for the island to be granted independence. Photo: REUTERS

NAHA (OKINAWA) — In a decrepit office below a billiard hall in the city of Naha, the capital of Okinawa in southern Japan, a small group is dreaming of a new country.

Surrounded by flags showing three stars on two bands of blue, symbolising the Okinawan sea and sky, they represent a revived movement for the Ryukyu Islands, which include Okinawa, to declare independence from Japan.

“Support for Ryukyu independence is growing,” said Mr Chousuke Yara, a perennial electoral candidate for the movement. “People are coming to understand that Okinawa was originally part of the Ryukyu kingdom, then invaded by Japan and made Japanese by education.”

The movement has a long way to go — a recent poll of islanders put support for independence at just 8 per cent. But another 21 per cent back full devolution and 88 per cent want greater self-determination — a sign of a growing alienation from the rest of Japan that could have profound consequences for regional security.

The Ryukyu chain, which stretches in a 1,000km arc from Taiwan to the Japanese mainland, is a natural barrier between China and the Pacific. The island of Okinawa is a cornerstone of the United States’ military presence in Asia, with US bases covering about 20 per cent of its land area.

There is a range of opinions on security in the independence movement, said Mr Yara. But his vision of a non-aligned and pacifist republic would send shivers down the spine of any US military planner.

“The Ryukyus and China have always had a friendly relationship, so there’s no reason to think the current Chinese regime would trouble us,” he said. “For example, if Japan were picking on us, we could have a military alliance with Taiwan or China, or the opposite, we could ally with the US and Japan.”

Resentment over the US bases has been a running sore point in relations between Okinawa and the mainland following incidents such as the rape of a local schoolgirl by US servicemen in 1995 and the crash of a US helicopter in 2004. Mr Shinzo Abe, Japan’s Prime Minister, wants to relocate the controversial helicopter base at Futenma to Henoko Bay in the north of the island, but locals want the base shut or moved off the island.

Mr Takeshi Onaga, Okinawa’s popular Governor, recently revoked a permit for building a new base at Henoko. Last week Mr Abe took out a court injunction against Mr Onaga and resumed construction. Elderly protesters outside the site at Henoko were dragged away by police after Mr Abe’s decision.

“I can’t restrain my furious resentment,” said Mr Onaga, elected last year on a mandate to oppose relocation of the Futenma base to Henoko. “The coercion continues.”

Dr Masaaki Gabe, a professor at the University of the Ryukyus, agrees that Okinawans feel distant from the government in Tokyo. “People feel Japanese but they also have feelings of discrimination by the Tokyo government,” he said.

Another incident such as the rape or the helicopter crash could change feelings towards independence, he added. “If there was a big event, and it wasn’t handled to the satisfaction of the Okinawan people, then it could have serious effects.”

The dispute over the US bases is the most significant issue between Okinawa and the mainland, but the island is diverging from Japan in other ways. With Japan’s highest birth rate, its population is ageing more slowly. And, unlike on the mainland, the island economy is growing fast.

Asian tourists are drawn by Okinawa’s blend of subtropical beauty and urban culture: Visitor numbers rose 10 per cent last year to more than 7 million, with the number of Chinese tourists more than doubling.

Okinawa is also trying to promote its strategic location to business as a potential logistics hub. The economy’s dependence on the military bases is down to about 5 per cent.

“We’ve gone from being an economy that relies on bases to the bases holding us back,” said Dr Masaki Tomochi, an economics professor at Okinawa International University and a leading light in the independence movement.

Dr Tomochi, who can see the Futenma base from his office, went to Scotland last year to support its campaign for independence from the UK and came back inspired. Okinawa was invaded by the Satsuma samurai in 1609, six years after King James I united the thrones of England and Scotland.

“Discrimination is not just in the past, it’s today — we’re still being discriminated against,” he said. “First, we need everyone to know the history of the Ryukyus. Then, we can think about the future.” FINANCIAL TIMES