Capitalism: In search of balance

When Pope Francis issued his first apostolic exhortation last month, he took aim at modern capitalism for encouraging “idolatry of money” and growing inequality in the world.

When Pope Francis issued his first apostolic exhortation last month, he took aim at modern capitalism for encouraging “idolatry of money” and growing inequality in the world.

“While the earnings of a minority are growing exponentially, so too is the gap separating the majority from the prosperity enjoyed by the happy few. This imbalance is the result of ideologies which defend the absolute autonomy of the marketplace and financial speculation,” the Pope wrote inEvangelii Gaudium (The Joy of the Gospel).

His words resonated with many people who face the seemingly inexorable rise of the richest 1 per cent and income stagnation among the middle class in advanced economies. For the world as a whole, however, the Pope was wrong on both counts. Not only has income distribution become more equal, but capitalism can take the credit.

The same forces that have hollowed out manufacturing and clerical jobs in the United States and Europe have lifted hundreds of millions of people out of poverty in China and India. They have made Western economies far more unequal, while tilting the global balance towards equality. The winners are factory workers in China and India; the losers the Western middle class.

The pressure of inequality has been building in industrialised societies for two or more decades, but the combination of the 2008-09 financial crisis and the inflated fortunes of the elite have reinforced them. The economic democracy of the mid-20th century is giving way to a distribution of wealth more like Edwardian or Victorian times.

“Straightforwardly, it’s about capital and labour,” says Dr Tony Atkinson, centenary professor at the London School of Economics. “We are seeing all sorts of changes that have benefited capital. That tends to equalise global wages, which means reducing them in rich countries.”

The tensions are exacerbated by inequality between generations. Postwar baby boomers enjoyed greater prosperity than their parents — steadily rising incomes, strong welfare states and defined benefit pensions.

Those born in the 1970s and 1980s have fewer benefits, face stagnating incomes in mid-career and must borrow more to buy expensive houses.

US President Barack Obama noted in a recent speech: “As good manufacturing jobs automated or headed offshore, workers lost their leverage and jobs paid less ... The top 10 per cent no longer takes one-third of our income — it now takes half. Whereas in the past, the average Chief Executive made about 20 to 30 times the income of the average workers, today’s CEO makes 273 times more.”

Yet the rise of China and India —two poor but populous countries — has made global inequality (measured by the disparity in individual incomes, regardless of where people live) less pronounced. The world’s Gini index of inequality fell between 2002 and 2008 — perhaps for the first time since the Industrial Revolution — and the growth of Indonesia and Brazil is pushing in the same direction.

“China is like a sumo wrestler who is fighting against global inequality,” says Mr Branko Milanovic, lead economist at the World Bank. “He is standing up against all the rest of the forces, but he is a big guy. Now, India has become a second sumo wrestler.”

Those changes are seen in Chart 1, which shows that two groups in the world did well between 1988 and 2008, achieving the highest real increases in their income.

The first was the rich — the top 10 per cent of earners and, within that, the 1 per cent. The other gainers were in the mid-tier — workers in emerging economies who were moving out of poverty.

The two groups that did worst were the very poor — those in the bottom 5 per cent, in sub-Saharan Africa and elsewhere, and the Western middle classes, both in the US and Western Europe and former Eastern Bloc countries. Their income rises did not match the luckier groups and, at the 75th percentile — including the US middle class — stagnated and even fell.

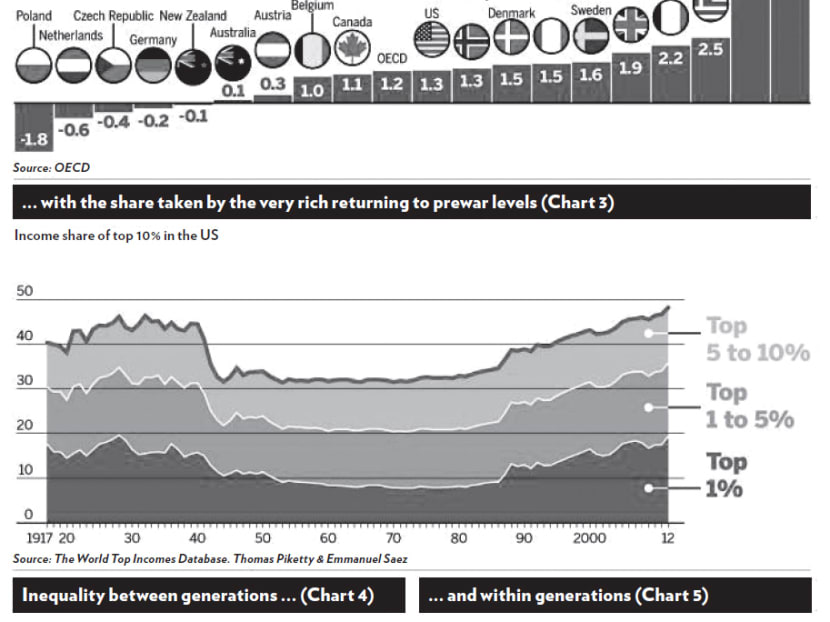

The rise in inequality in Western nations is evident in Chart 2, which shows nations where the Gini index rose — meaning greater inequality —between 2007 and 2010. That group includes the US and United Kingdom, but also a range of European countries such as Italy, France and Spain.

The third chart shows the growing share of income taken by the upper US echelon. Work by Professors Emmanuel Saez and Thomas Piketty, two economists, shows that the top 10 per cent of earners took about 45 per cent of income between the 1920s and 1940 but the share fell to about a third until the 1970s. Since then, aided by trade liberalisation and deregulation, it has risen sharply. The top 1 per cent have done best of all.

As Prof Saez notes, the top earners in the US are mostly not rentiers, living off income from wealth and property. Instead, they are the working rich — such as bankers and lawyers — and entrepreneurs who have “not yet accumulated fortunes comparable to those accumulated during the Golden Age”. But he argues that this distinction “might not last very long”.

That is also suggested by Charts 4 and 5, from the UK Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS), analysing inequality between age cohorts. Chart 4 shows that adults born in the 1960s and 1970s —the post baby-boomers — are starting to undershoot the income of former generations at the same age. The pattern for today’s 40-year-olds is bleak, since their earning power peaked 10 years ago.

These 40-year-olds are likely to depend increasingly on inheriting wealth for a comfortable retirement. But Chart 5 shows that the well-off expect to inherit the most, while those on lower incomes expect little help. “Inequality that starts out as being between generations may end up within generations,” says Mr Andrew Hood, an IFS research economist.

The tensions created by these trends are evident — from the Occupy protests against the “1 per cent” to trade and currency disputes between the US and China, and political pressure on global companies to pay more tax. President Obama has declared it “the defining challenge of our times”.

If so, it is a complex one. The forces producing the dispersion of income and wealth in Western countries are hard to reverse. They are also the forces that have helped the emerging middle class of China, India or Brazil.

“The Pope loves everyone, rich and poor alike, but he is obliged in the name of Christ to remind all that the rich must help, respect and promote the poor,” wrote Pope Francis.

“I exhort you to generous solidarity and a return of economics and finance to an ethical approach which favours human beings.” The question is: Which ones? THE FINANCIAL TIMES

John Gapper is Associate Editor and Chief Business Commentator of the Financial Times.