Chinese magazine harassed by censors prepares for battle

BEIJING — The cluttered offices of a history magazine in Beijing have become an unusually public battlefield in China’s ideological wars.

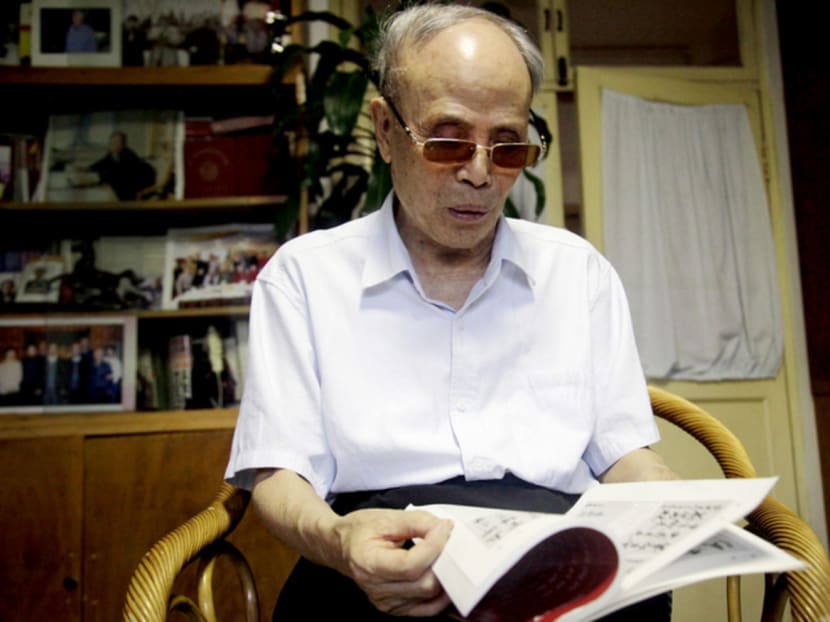

Mr Du Daozheng browsing through his Yanhuang Chunqiu magazine at his home in Beijing. Its survival is in doubt as the authorities try to install editors who will march more closely to the political tune of President Xi Jinping. Photo: AP

BEIJING — The cluttered offices of a history magazine in Beijing have become an unusually public battlefield in China’s ideological wars.

For 25 years, the monthly magazine Yanhuang Chunqiu has survived the ire of censors, protected by moderate-minded retired officials who used it to call for limited political liberalisation, market overhauls and an honest reckoning with dark periods in the Communist Party’s past.

But the magazine’s survival is in doubt as the authorities try to install editors who will march more closely to the political tune of President Xi Jinping. That would end the magazine’s relative independence, and editors have said they would rather let it die than continue compromised.

“It’s better to be shattered jade than an intact tile,” said Mr Du Daozheng, the founding publisher of the magazine in an interview. He was using an old saying that means perishing with integrity is preferable to unprincipled survival.

“With the way that they’ve treated Yanhuang Chunqiu, we no longer have the conditions for survival,” said Mr Du, a former head of the General Administration of Press and Publication. “We’ve been forced into a corner.”

Editors resisting the changes said the upheaval reflected the party’s intensifying offensive against unorthodox ideas. Yet they have chosen open resistance, using a lawsuit, a standoff at the magazine’s offices, and gestures of support from academics, writers and senior retired officials.

Quarrelling erupted at the magazine’s office on Tuesday, when Mr Hu Dehua — a son of the reformist Communist Party leader Hu Yaobang and a deputy publisher of the magazine —tried to enter with journalists and was blocked by plainclothes guards who refused to say for whom they worked.

“This is our office,” Mr Hu told a man in a blue shirt who was directing the guards. “What are you doing here? This is our office. Who told you could be here?”

The guards eventually let Mr Hu in to deal with the magazine’s tax affairs, provided the journalists remained outside.

If Yanhuang Chunqiu dies, or becomes a ghost of its old self, it will be a signpost of how limits on expression have tightened under Mr Xi.

“What has happened shows the big changes in China’s political environment,” said Mr Wu Wei, the executive editor of the magazine, in an interview. He took up the job only a month or so ago.

“I don’t know whether we’ll be able to resume publication or stop entirely,” said Mr Wu, who once served as an aide to Zhao Ziyang, the party leader purged during the political upheavals of 1989. “Ending Yanhuang Chunqiu would take away a voice for reformists inside the party.”

The magazine, whose title roughly translates as China Annals, has survived many run-ins with censors. But the worst threat yet came this month, when the government-run Chinese National Academy of Arts, which officially oversees the magazine, announced it would install a new editorial lineup.

The publisher, Mr Du, 92, and his supporters have also tried to sue the academy for breach of contract, claiming that the changes violated an agreement reached in 2014 that promised the magazine autonomy over personnel, finances and editorial choices. But a court in Beijing has so far refused to accept their case and is still considering what to do, said Mr Ding Xikui, one of the lawyers representing the aggrieved editors.

The rift over the magazine’s future has also become a physical standoff, with separate parts of its premises, behind a small hotel in western Beijing, held by the two rival groups.

On Tuesday, the distribution office was still run by staff members loyal to the longtime editors, while nearby, an editor’s office and meeting room were held by people apparently loyal to the academy that has tried to impose control over the magazine. So far, the police have not moved against the protesting editors.

Since it started in 1991, Yanhuang Chunqiu has made an art of staying in the bounds of censorship while challenging orthodoxy. Mr Du said the magazine’s motto was “democracy and rule of law, and market economics.”

Its print run has been about 190,000 copies each month, according to Mr Du. But it has won an outsize influence because it has served as a platform for retired senior party officials who want China to pursue measured liberalisation.

Many of its backers were reformers whose influence peaked in the 1980s. And many also served, and suffered, under Mao, and believed China must confront its legacy to move forward.

“From 1949 up to reform and opening up, over 100 million people were persecuted across the country,” wrote Mr Li Rui, the former secretary of Mao, who became an advocate for political liberalisation and a supporter of the magazine in 2007. “This was the harrowing and malignant result of a failure to establish democracy and checks and balances on power.”

Another of the magazine’s patrons was Mr Xi’s father, Xi Zhongxun, a former party leader who praised the magazine in 2001. And when the younger Mr Xi came to power in 2012, some people held hopes that his family background and experiences of suffering under Mao would encourage him to tolerate, if not heed, more liberal voices in the party.

But Mr Xi has instead adopted a staunchly traditionalist political line, warning against political liberalisation and defending Mao’s revered status.

Precedent suggests that the defenders of Yanhuang Chunqiu’s autonomy have little hope of winning. Other magazines and newspapers brought to heel by officialdom have either closed down or survived as tepid replicas. But this time, the editors appear determined not to go quietly.

“This is a magazine that speaks the truth,” Mr Hu, the deputy publisher, told several reporters outside the Yanhuang Chunqiu offices, while guards recorded videos on their smartphones. “There’s an old Chinese saying that even a rabbit will bite when it’s riled.” the new york times