How traditional Chinese acupuncture with an electric twist could help fight cancer

HONG KONG — Electrically charged acupuncture needles that can significantly reduce the size of tumours could open the way for a safe, low-cost cancer treatment, according to a new study.

HONG KONG — Electrically charged acupuncture needles that can significantly reduce the size of tumours could open the way for a safe, low-cost cancer treatment, according to a new study.

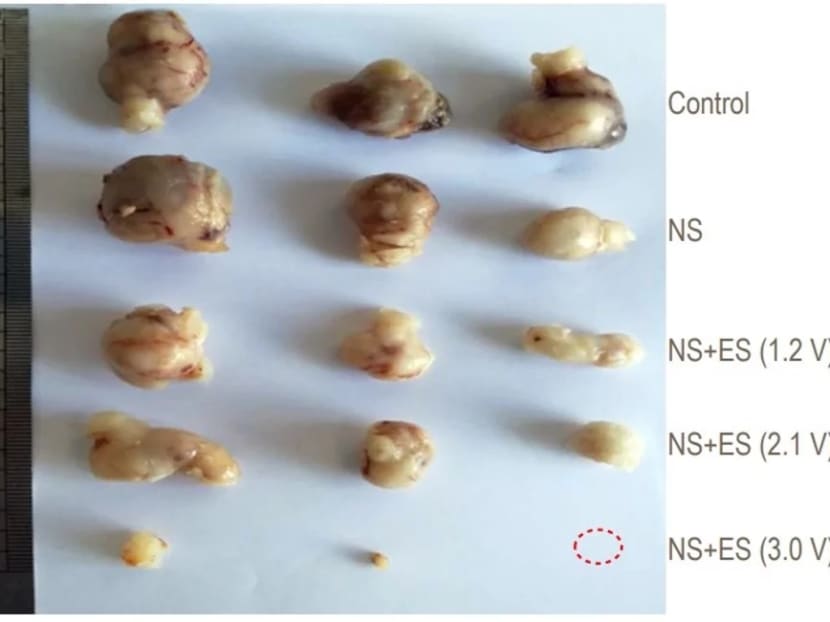

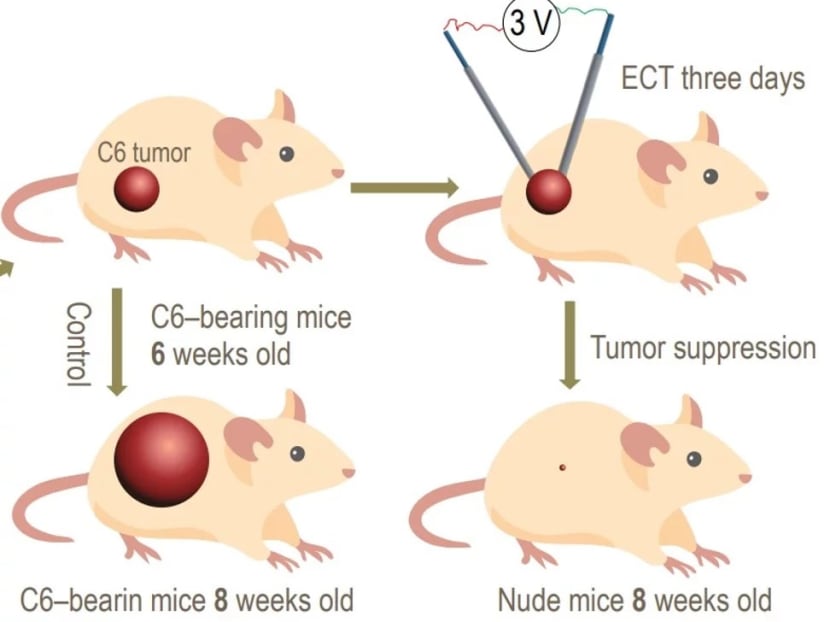

A team of Chinese scientists adapted the traditional technique to create a form of “electro-chemotherapy” to treat laboratory mice with brain tumours, shrinking them to less than 1 per cent of their initial size.

The team, from the State Key Laboratory of Electroanalytical Chemistry, inserted a pair of insulated needles into the heads of the mice and pierced the tumours with the charged tips — one negative and one positive.

When the electric current was turned on it broke water molecules down into oxygen and hydrogen, the latter making the cancer cells “burst and die”, according to a paper published this month in National Science Review.

The mice were given a twice-daily, 10-minute dose of the treatment over three consecutive days.

Sixteen days after the treatment started the tumours, which were around the size of a bean, had shrunk to just 0.38 per cent of their original size — scarcely visible to the naked eye.

Lead researcher Jin Yongdong, from the Changchun Institute of Applied Chemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences, then repeated the experiment on mice with breast cancer and the result was almost the same.

Mr Jin wrote that this was the first time that “controllable in-vivo hydrogen generation” had been successfully applied as a tumour therapy.

He said this “electro-chemotherapy” was “simple, highly efficient and minimally invasive, requiring no expensive medical equipment or (nano) materials and medication, and is therefore very promising for potential clinic applications”.

The “electro-puncture” technique used in Mr Jin’s study was inspired by traditional Chinese acupuncture, but faces the same challenge all oncological treatments face: namely, applying them safely.

For example, chemotherapy, which uses poisonous chemicals to kill tumours, also damages healthy organs in the process and, according to some estimates, only 0.01 per cent of chemotherapy drugs actually reach the tumour and its diseased cells.

When Mr Jin’s team looked for side effects in the cells and the tissues of the mice treated with the charged needles they found no statistically significant changes had occurred.

But the voltage has to be carefully controlled and after many experiments the team concluded that 3 volts was the optimal level — high enough to be effective but low enough to cut the risk of causing discomfort, injury or death.

The paper said the technique appeared “promising and reliable” in treating solid tumours, but currently may not be valid for non-solid tumours such as lung or liver cancers.

The hydrogen molecules created by the process presented another problem for the researchers, who have yet to determine how or why they killed the cancer cells.

However, one possibility is that the hydrogen might have disrupted the micro-environment in which the cancer cells thrive, by changing the pH level inside the tumours from an acidic 5.5 to a neutral 7.5.

According to this theory, the hydrogen may work as an antioxidant that reduces the number of cytotoxic oxygen radicals, which previous studies have linked to tumour growth.

However, further research will be needed to validate this theory.

Hydrogen molecules are small enough to penetrate the membranes of cells and critical components such as the nucleus and mitochondria, and scientists have tried to exploit this to treat a range of conditions such as Alzheimer’s, arthritis and diabetes.

However, the results have been mixed so far and it is difficult to deliver a large, stable amount of hydrogen into the human body.

Mr Chen Hao, a researcher with the Shanghai Institute of Materia Medica, said that cracking the underlying mechanism behind the phenomenon would be the key to developing clinical applications.

“Using a new drug or therapy in hospital will need approval, and to get the approval they need to explain to food and drug authorities how it works,” said Mr Chen, who was not involved in the study. “This rule is very strict.” SOUTH CHINA MORNING POST