Boss, do you have to be a jerk?

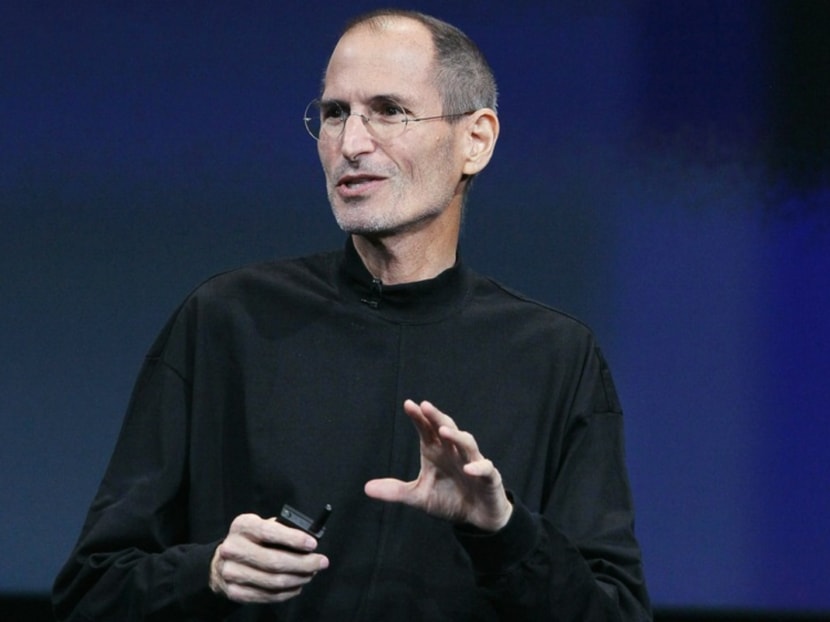

Steve Jobs, the late Apple chairman and chief executive, was renowned as an uncompromising, abrasive and impatient leader who exerted control over every aspect of the business in his quest for perfection. But he also founded and led Apple to become one of the world’s most successful and valuable companies, creating ground-breaking products. This raises the question: Does a leader have to be a jerk to be successful? Here, five faculty members from the National University of Singapore Business School’s Department of Management & Organisation give their views on an enduring question.

Steve Jobs, the late Apple chairman and chief executive, was renowned as an uncompromising, abrasive and impatient leader who exerted control over every aspect of the business in his quest for perfection. But he also founded and led Apple to become one of the world’s most successful and valuable companies, creating ground-breaking products. This raises the question: Does a leader have to be a jerk to be successful? Here, five faculty members from the National University of Singapore Business School’s Department of Management & Organisation give their views on an enduring question.

Head of Department Professor Michael Frese

Steve Jobs is often held up as an example of a successful but abhorrent leader. He was, but he was also something else: A visionary and a magician. He had a rare ability to paint what was possible and drive people to achieve it by giving everything.

That is not to say that being a jerk was necessary to Jobs’ success, but a critical part of leadership is about execution — turning vision into reality. In Jobs’ case, the success he brought to Apple was largely due to the high standards he expected. To meet those standards, he motivated those around him to pour their all into achieving his vision and did so largely through criticism.

Criticism can be highly stimulating if those it targets have the self-confidence to believe they can improve. In large part, Jobs surrounded himself with personalities who fitted that mould. But in other situations, relentless criticism can be deeply counterproductive, demoralising and ultimately destructive.

Like Einstein, Picasso and other geniuses of their trade, Jobs achieved success through single-minded dedication. Everything else was secondary. But his genius was not because he was a successful jerk; his genius was that he was a success despite being one.

Assistant Professor Amy Ou Yi

The characteristics of the abrasive leader are closely related to narcissism — those who believe in their own superiority and look for reaffirmation by demeaning others. Narcissistic chief executive officers favour dynamic and grandiose strategies, and pursue more and bigger acquisitions. But their impact on firms is often to create more extreme and fluctuating performance.

Steve Jobs was often described as a narcissistic leader and in 1985 was fired from Apple as a result. He later described the experience as “awful tasting medicine”, but acknowledged it was something he had needed.

Studies suggest that humility — recognising one’s own limitations and appreciating others — can restrain narcissistic CEOs. Like the reins on a horse, humility prevents characteristics such as narcissism from reaching an extreme. While narcissism demands power over others, humility enables CEOs to build a communal power base, achieving goals by working collaboratively.

My own research shows that humble CEOs are willing to narrow the pay gap with top management team members, developing strong teams that make decisions together and form a common vision.

In this way, humble leaders build loyal and highly-motivated managers, and achieve extraordinary performance. Other research concurs that when narcissism is tempered by humility, leaders become more effective, more charismatic and more innovative.

Associate Professor Jayanth Narayanan

Research on how we store, process and use information about other people — known as “social cognition” — suggests that we make judgments on two primary dimensions: Warmth and competence.

Warmth encompasses qualities such as likeability and sociability, whereas competence encompasses qualities such as ability.

Studies have shown that warmth matters more than competence when people decide whom they choose to work with. They prefer the lovable fools over the competent jerks. So why is the idea of an effective but boorish leader so alluring?

In my research we examined how people think about being likeable versus being competent.

Many people assume they are related and, even more worryingly, our education system rarely, if ever, provides feedback on warmth-related dimensions, raising a generation to believe that competence is all that matters.

As a result, people looking to signal their competence may seek to be low on warmth and become a brash leader in the process.

The trouble is that this flies in the face of evidence that warmth is a key attribute for workplace success. As my grandmother said, be nice and the world will treat you well — wise advice for any leader.

Visiting Professor Richard D Arvey

Being a jerk of a manager at any level within an organisation is something generally not going to work well. Yes, we have seen several high-profile examples of petulant leaders who have led their company to game-changing success. But was it the fact they were uncompromisingly abrasive that was the deciding factor?

By far, the majority of research shows that abusive behaviour by managers tends to alienate subordinates who, understandably, leave if given the opportunity.

Haemorrhaging talent is not a great path to a sustainable business, and unless you are already at the top of the firm, being one who is downright rude is no guarantee of promotion.

That said, there is little doubt that many successful companies have leaders who might fit into that category.

So we should ask why people tolerate abuse from such reprehensible managers.

In the case of Steve Jobs, I suspect that many of his employees enjoyed great compensation through stock ownership. If the company was not so successful — and if that success was not so clearly identified with Jobs himself — would they have stayed? I doubt it.

Associate Professor Daniel McAllister

Driving change in today’s complex and resource-constrained world requires a full arsenal of capabilities, a willingness to confront resistance, and a readiness to take positions that are not necessarily popular.

From time to time, truly transformational leadership requires one to be heartless, abrasive and a complete jerk.

We cannot expect that all leaders be tough guys all the time, but I am not convinced either that being an abrasive boss necessarily disqualifies someone from leadership.

Some leaders go overboard and use force where it is not appropriate, but the alternative of requiring that leaders always be nice guys would be unwise, even damaging.

Machiavelli’s 16th century advice remains relevant: Use as little force as necessary to accomplish a goal, but also be prepared to use sufficient force to ensure successful goal accomplishment.

Tough bosses, teachers, coaches and drill sergeants often have keen insights into human psychology, care deeply for their followers as well as performance objectives, and are skilled at bringing out the best in people. Just as importantly, they are often clear thinkers and level-headed, even during the toughest of times.

At the end of the day, what matters most? Is it more important that a leader maintain a reputation of being nice, or that the hopes and aspirations of the organisation and followers are reached?

Perhaps true leader humility means being prepared to forgo the short-term reputational benefits of being seen as a nice guy when the situation requires you to take an unpopular stand that better serves the organisation and its mission.

This is part of an ongoing weekly series on leadership.