Going beyond a culture of mastery

The potential of education to be a powerful instrument of social transformation is undeniable.

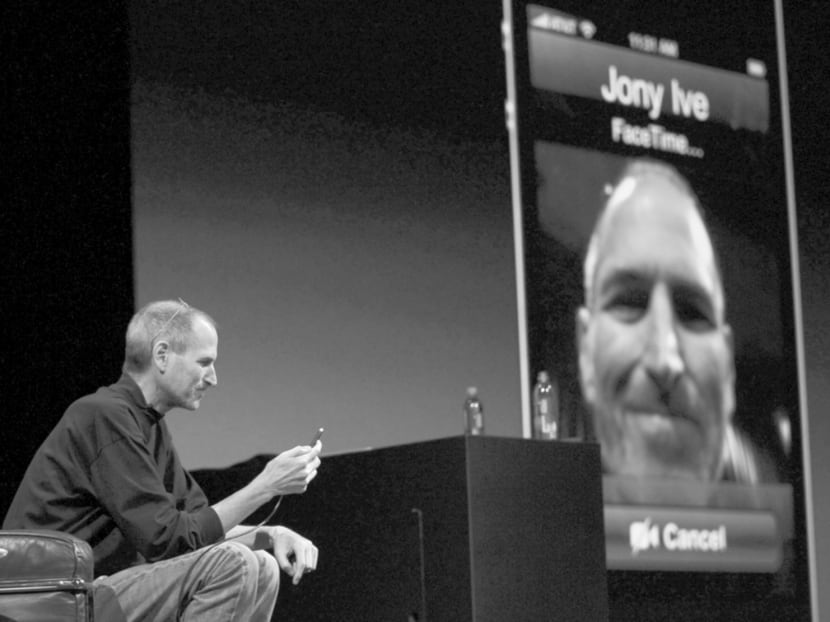

The success of the iPhone was largely due to Steve Jobs’ ability to ‘connect the dots’ in unusual ways, drawing together technology, design, marketing and an intuition about consumer preferences. Given his experiences and environment, he simply had more dots to connect than others did. Photo: Reuters

The potential of education to be a powerful instrument of social transformation is undeniable.

The launch of SkillsFuture, a national initiative to provide Singaporeans with opportunities to master different skills at various stages of life, should therefore be lauded. The sheer range of courses — some 10,000 courses are listed in the SkillsFuture Credit Course directory — is staggering. More importantly, placing a “culture of mastery” at the heart of lifelong learning is a positive and enlightened step.

But this is not enough. The proliferation of courses cannot possibly keep pace with an increasingly complex world. Furthermore, in the face of growing uncertainty, a culture of mastery hits an inevitable limit: Some things simply cannot be mastered.

Also, as Acting Minister for Education (Schools) Ng Chee Meng said in a recent speech, Singapore needs more than problem solvers; it needs “innovators, inventors, path-blazers, people who can push the envelope, who can create value for society”. We need people who can solve complicated problems as well as complex mysteries.

So how do we teach the ability to deal with the complexity and uncertainty that lie at the heart of innovation and entrepreneurship?

First, we must learn to appreciate the limits of knowledge. Education, from as early as possible, should show there is no learning that is immune to error. Clearly, rationality remains the best safeguard against error, but it must be a constructive and humble rationality that remains open to ideas that might disagree with it. Without this openness, rationality itself becomes perverted into dogmatism and fundamentalism.

What is needed is not merely a critical rationality, but a self-critical one. History is full of examples of societies, such as the Roman Empire and the various Chinese dynasties, that were successful because of their innovations in the arts, sciences and technology, but eventually atrophied and collapsed because of hubris, complacency and inability to engage with uncertainty.

Second, we must acknowledge that the human mind is inherently limited and flawed, and that mystery is an inescapable, at times even welcome, part of the human condition. To engage with life’s mysteries, we need to reclaim the original meaning of pragmatism, usually taken to mean hardheadedness. We need to recover the spirit of experimentation and the flexibility of thought that are the hallmarks of pragmatist philosophy.

In this, we do not need to look so far back in time or across geography to American pragmatists such as John Dewey and William James. Pragmatists basically believe in the testing of ideas, that ideas must be evaluated in terms of how useful their practical applications are.

The pragmatic mindset is best captured by the late Mr Lee Kuan Yew. In a 2007 interview with The New York Times, Singapore’s founding Prime Minister said: “We are pragmatists. We don’t stick to any ideology. Does it work? Let’s try it and if it does work, fine, let’s continue it. If it doesn’t work, toss it out, try another one.”

And finally, we must learn to not only embrace uncertainty, but to understand that all progress is the fruit of uncertainty that changes the system within which it first arose. This is particularly relevant to our era.

Primitive societies lived in the relative certainty of predictable time, which they believed were maintained through rituals, sacrifice and magic. The Industrial Revolution brought with it the belief in the inevitability of progress. Today, that unbridled optimism has been tempered by a profound awareness of uncertainty.

And, yet, we still persist with the tried and tested: A report published by the Foundation for Young Australians in August last year said 60 per cent of Australian students are being trained for jobs that will not exist or will be fundamentally transformed by automation. Alas, Australia is not unique in this.

Amid uncertainty, the prospects of any society will depend a great deal on the imagination of its people. But imagination cannot be produced by administrative dictat, by some “plan”. Rather, this imagination is paradoxically produced by, and flourishes within, uncertainty: The diversity in society, the space to explore, and the messiness of experiments.

If anything, the “plan” must be confined to protecting that imagination from the tempting security of conventionalism and false certainties. We must acknowledge that all actions in complex environments are essentially bets, and that there is no model answer. Hence, the ability to imagine and adapt becomes even more important than the ability to plan.

The success of the iPhone was largely due to former Apple chief executive Steve Jobs’ ability to “connect the dots” in unusual ways, drawing together technology, design, marketing and an intuition about consumer preferences. Given his experiences and environment, he simply had more dots to connect than others did.

Beyond mastering what is masterable, we need to cultivate what the poet John Keats termed “a negative capability”. It is the ability to contemplate the world without the desire to force its contradictory aspects into a closed and coherent whole.

Learning how to be comfortable in uncertainties, mysteries and doubts may well be the silver bullet for thriving in a complex world. Ultimately, the most positive thing we can teach our students may well turn out to be this “negative capability”.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Dr Adrian W J Kuah is Senior Research Fellow at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, National University of Singapore.