Lessons from Asean for Xi’s Belt and Road Initiative

Analysts the world over have thoroughly scrutinised the recently-concluded Belt and Road Forum in Beijing, from the forum outcomes’ significance and China’s emergence as a global leader to the invitation list.

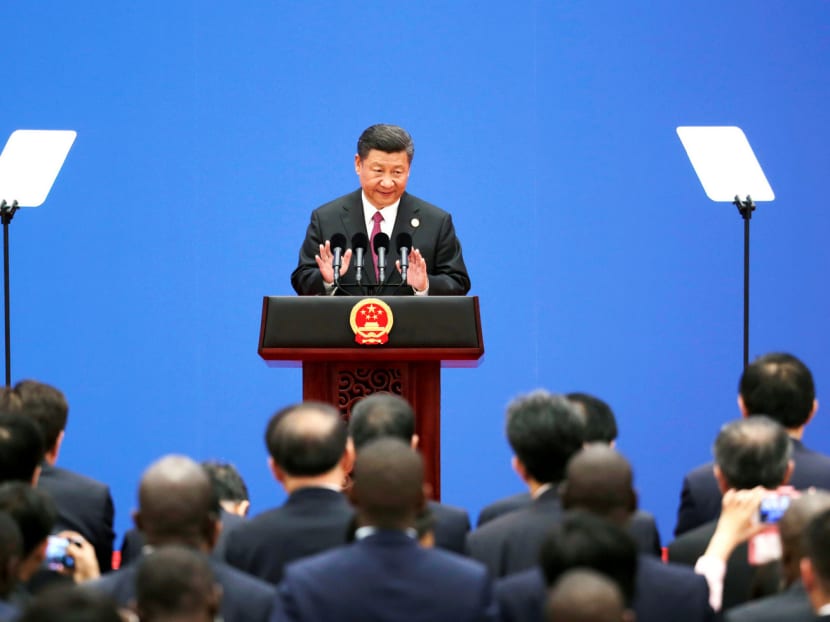

Chinese President Xi Jinping at a news conference at the end of the Belt and Road Forum in Beijing last week. China is offering a large pie to the world but has kept details vague. Photo: Reuters

Analysts the world over have thoroughly scrutinised the recently-concluded Belt and Road Forum in Beijing, from the forum outcomes’ significance and China’s emergence as a global leader to the invitation list.

One thing is for sure: China is offering a large pie that is worth hundreds of billions of dollars. Not only has President Xi Jinping repeatedly assured the world that all are welcome to partake in the feast, all are also even welcome to suggest, and make, changes.

There are many hungry mouths, and everyone wants to know how this pie will be distributed. How will individual countries, regional and international groupings attract China’s attention to get their share? Who gets what, based on what criteria? Who exercises governance and to what extent?

The summit in Beijing underscores the non-institutionalised nature of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The joint communique and list of 270 outcomes are impressive but China stopped short of offering a formal framework for the BRI.

This “big family of harmonious co-existence” requires clearer, if not targeted, guidelines, governance and avenues of recourse. China’s fear of being labelled a revisionist power bent on creating a disruptive economic clique is a major block for the development of such a blueprint.

It is a vicious cycle — the more China refrains from articulating its initiatives, the more suspicion it receives from the international audience.

China’s own lack of domestic consensus on the BRI is another major stumbling block. Opportunistic policymakers in China’s central and provincial governments, as well as profit-driven state-owned enterprises, treat the BRI as a convenient carryall that accommodates a very diverse array of development plans and ad hoc projects.

Even as Mr Xi hosted dozens of world leaders at the Beijing summit, domestic and external coordination of policies remain rudimentary and fragmented.

This leaves both China and regional countries vulnerable to risky investment projects, corruption and opposition from local communities threatened with displacement by infrastructure development projects.

Whatever its misgivings, China could start with a domestic blueprint and set up a concrete framework for implementation and governance. This would allow transparency for scrutiny, which would convince the international audience of the BRI’s efficacy and allay fears that China is exporting its development issues. The domestic blueprint can then be expanded into a regional and global blueprint.

From the strategic sense, the BRI’s ambiguity is working in China’s favour. It allows Beijing to retain control and exploit existing rivalries using the divide-and-rule strategy to achieve specific Chinese foreign policy objectives.

THE ASEAN CONNNECTION

In the case of South-east Asia, BRI is increasing competition among Asean members. Speculation has been rife that countries will be intentionally marginalised if they fall out of Chinese favour.

This fear of marginalisation and losing out to a regional competitor, in turn, has created domestic pressure on regional governments. It also carries the danger of increasing strategic mistrust. Can Asean do anything?

Asean connectivity is the foundation for the development of enhanced connectivity in East Asia.

It was recognised as a key element in building an East Asian community during the 15th Anniversary of Asean Plus Three (APT) cooperation in 2012.

The importance of Asean’s central role in the evolving regional architecture was also reiterated at the 15th APT Foreign Ministers’ Meeting in 2015.

During his keynote speech at the summit’s opening ceremony, Mr Xi cited the BRI’s tie-up with Asean’s connectivity master plan, the Master Plan on Asean Connectivity (MPAC), as an example of Beijing’s efforts to enhance policy coordination with relevant regions and countries.

The MPAC was adopted in 2010 by South-east Asian leaders to support the building of an Asean community. It identified 15 priority projects, including the Singapore-Kunming Rail Link and the Asean Highway Network.

Currently in its second phase, the MPAC 2025 draws on extensive research of the 15 projects’ progress and highlights six core areas critical for effective government delivery.

These include having a strong focus and targets; ensuring clear governance and ownership; and establishing an impartial and robust performance-tracking system.

However, apart from China’s interest in the flagship Singapore-Kunming Rail Link project, there is little evidence of to show how exactly the BRI is synchronised with the MPAC on institutional connectivity, particularly on issues such as property rights, cost-benefit sharing and project oversight. Asean is working on improving governance for its physical infrastructure projects.

For instance, it identified the lack of regulatory structures (property rights, relevant standards and protocols) and frameworks for negotiating cost-benefit sharing of cross-border infrastructure projects as important implementation barriers, particularly for rail projects.

Regardless of Asean’s shortcomings, its connectivity experience, particularly institutional connectivity, is relevant to China.

More importantly, if Asean plays a substantive role in driving Asean-China cooperation, this will mitigate fears of Chinese domination to a certain extent.

In my discussions with Chinese and South-east Asian scholars, some have argued that it is better for Asean and China to keep MPAC and the BRI separate. The Chinese camp has posited two contentious points: First, the MPAC is largely funded by Japan for its own production network and does not take into consideration China’s needs; second, Asean is too slow.

Some Chinese scholars are not aware of the MPAC’s existence. The South-east Asian camp, on the other hand, feels that the MPAC should address Asean’s needs first. This risks duplication of work and inefficient use of scarce resources for overlapping projects. It also risks criticism that China wants to work only on its own terms and to dominate where possible.

The BRI is here to stay. Asean should take a more proactive approach in promoting its regional connectivity efforts and strengths, not only to maintain Chinese interest in the region but also to safeguard regional interests.

The Asean Secretariat, Asean Connectivity Coordinating Committee and relevant agencies should be strengthened to deal with the incoming wave of Chinese development investments. If properly implemented, MPAC 2025 can provide a framework of governance for BRI-linked regional projects.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Irene Chan is a Associate Research Fellow with the China Programme in the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University.