Class of its own: What makes Intercultural Theatre Institute different

“There is a deep disconnect between cultures in Singapore,” says T Sasitharan, Cultural Medallion-winning actor and director, and founder of the Intercultural Theatre Institute (ITI).

“There is a deep disconnect between cultures in Singapore,” says T Sasitharan, Cultural Medallion-winning actor and director, and founder of the Intercultural Theatre Institute (ITI).

“In our public spaces, people from different ethnicities often interact in a regulated, authorised way, which is sometimes necessary. That’s multiculturalism. But I think we need to get deeper than multiculturalism. We need to understand what our differences are, and accept rather than avoid inevitable conflicts. If we deal with these conflicts and discover how to work together as a group, that’s interculturalism.”

In 2000, Sasitharan and the late legendary playwright-director-activist Kuo Pao Kun founded the Theatre Training & Research Programme to produce artistes who work interculturally.

It trained diverse students in classical Asian and Western performance traditions, ideally resulting in creations of works that might not obviously contain Indian, Malay, or Chinese art forms, but instead come from conversations between cultures and thus, often be more authentically Singaporean.

Sixteen years on and a change in name — to ITI — later, the school continues in its unique focus, setting it apart from most schools who often embrace specialised art-forms.

A DIFFERENT SCHOOL

Yet that’s probably not the most immediately obvious difference between ITI and other educational institutions. Instead of having a sprawling, state-of-the-art campus containing theatres and cafes, such as Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts or LASALLE College of the Arts, the school occupies a few spaces in a weathered colonial bungalow compound at Emily Hill in Upper Wilkie Road.

Instead of cohorts boasting hundreds of students, the total alumni from ITI’s 15-year history numbers just shy of 50 (though students hail from as far as Bolivia and Mexico, and all continue to gain recognition for their work in theatre, like Golden Horse Award-winning Yeo Yann Yann).

During their full-time three-year course, students are expected to clean the school spaces and prepare their own food, since there are no stalls or vending machines in the compound or nearby.

And all of this is part of the learning process. “This is the character of the school,” said Sasitharan. “Class sizes are small to facilitate learning, and also because we are very careful with the composition of each group — what they speak, where they come from — to facilitate intercultural collaboration. We have turned applicants away because they don’t quite fit the mix.

“As for cooking their own food, cleaning, or constructing things for themselves rather than just buying something, that’s part of the experience a student has to have in order to become an effective artiste. Artistes are not made through comfort. They need to go through a type of human experience, to live in a certain kind of way and learn to understand life in a certain way. “

“Physically and emotionally, we are pushed to the limit from 8am to 6pm every day,” confessed current student Catherine Ho. “There are days when you really wonder: ‘What am I doing here, am I strong enough to continue?’ It’s been especially hard recently because my paternal grandfather had heart surgery and then my maternal grandmother passed away. I have had to take a few hours off because of these, but especially when rehearsing for a production, there’s so much to accomplish each day that despite the exhaustion, I have never taken a full day off. My mother was p***ed off with me, but all this has made it very clear for me what kind of work ethics I can and want to uphold as an actor.”

While Sasitharan stressed that the students’ spartan routines would not change even if they had the funds to build luxurious canteens and hire an army of cleaners, ITI is not exactly swimming in cash.

“There’s no way ITI can be sustained by school fees unless we have a hundred students each year, and that’s not what we want. What we do want is to provide scholarships and bursaries for our handful of students because very few can pay the fees for the full course on their own.” (Both Yeo and Ho would not have been able to study theatre at all without ITI scholarships.)

He continued: “But we’re a private school; we don’t have capitalisation grants from the Ministry of Education like the other arts schools. Instead, we have a development director who works 24/7 year-round, approaching anyone and everyone to raise funds. It’s hard work.”

BREAKING BARRIERS

It’s grueling work indeed, with, admittedly, a tiny crop of students to show for it — so why does ITI keep at it?

“For the work the students do, of course. Many people tell me they can identify ITI students by their craft, their discipline, their attitudes towards diversity. Add that to their work getting recognition and awards … that’s why we keep going,” said Sasitharan.

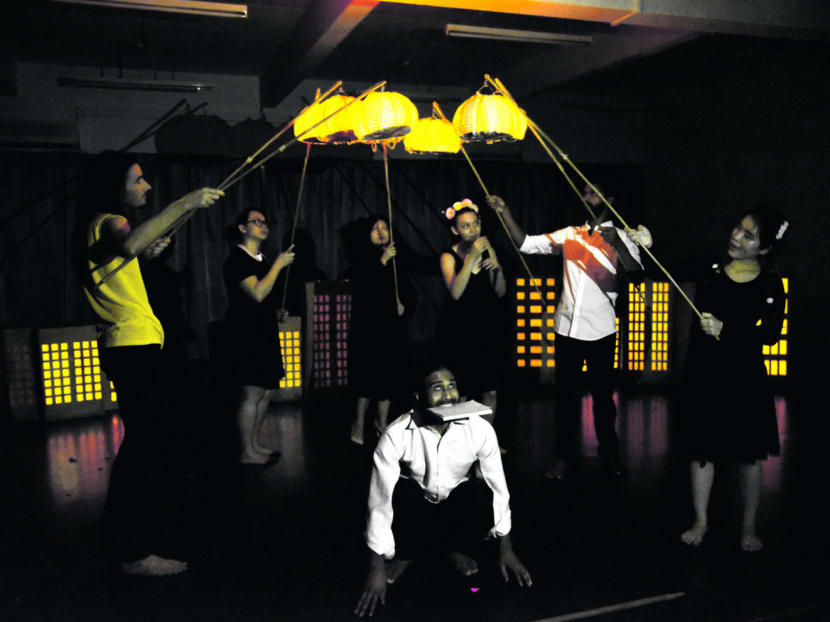

ITI’s latest ambitious intercultural work kicks off on Thursday. Titled Simplicity, it’s directed by multi-award-winning Argentinian theatre-maker Guillermo Angelelli and inspired by various works of Argentinian poet Jorge Luis Borges.

Devised by ITI’s current cohort, the work will be performed in numerous languages and dialects from Portuguese to Cantonese to Tamil, and incorporate elements from various traditional art forms.

Student Ho, who’ll be performing, elaborated: “Again, we’re not ‘performing’ artforms like Beijing opera per se, but you’ll see elements of what we’ve learnt from it. If you glimpse somebody walking in a certain stylised way, which could be drawn from Beijing Opera — the intercultural training just adds to our vocabulary.”

While devising Simplicity, the students also offered songs and other material they’ve been exposed to in their respectively cultures. “Because of language barriers we will first explain to each other the content of the material, and why it’s relevant to the play, or to us personally,” she said.

“But really, language is no longer an issue among us. We’ve been classmates for two years and counting: We’ve eaten together, learnt to cook each other’s cuisine … We understand and accept each other. Basically, I’d say that theatre training, especially in ITI, helps you as a person to be very open, less judgmental and more accepting, and thus just a happier person, instead of uptight and constantly offended.”

While that’s all great for the student performers, will a less multilingual audience be able to enjoy Simplicity?

Said Sasitharan: “The key factor here is poetry, an element in each of our lives, whatever the culture. But this sense of poetry in our lives can be easy to miss, and this performance delves into that using several cultures and languages.”

He added: “What we aim to do in general is to create a quality of performance that transcends language. When you go to see a good opera, even without translations, you can follow what they are saying. If the craft is good, that arrests you — and that is the level we are always aiming for.”

Simplicity runs from March 17 to 19 at the Drama Centre Black Box. Tickets from http://simplicity.peatix.com. For more on ITI, visit http://iti.edu.sg/