A place for all

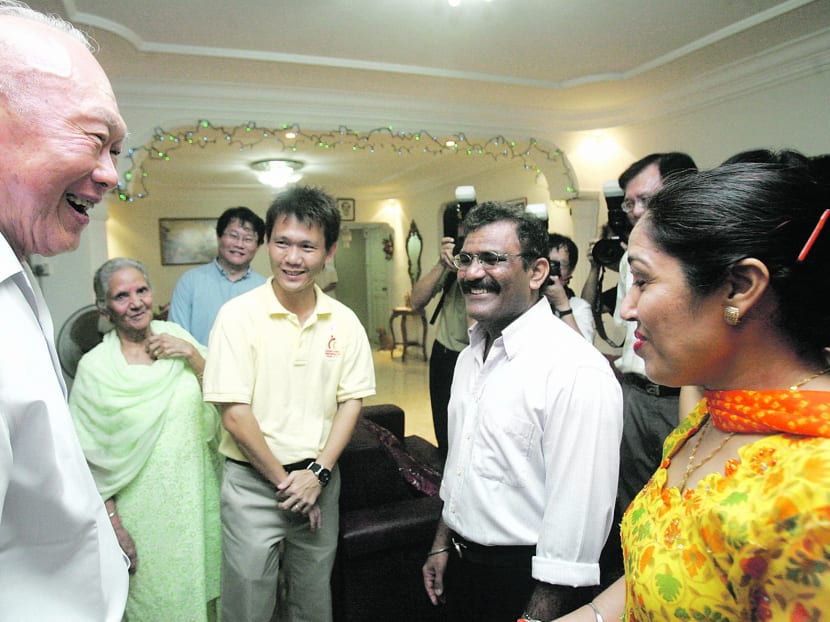

He was the man who wove multiculturalism into the very DNA of Singapore, in the conviction that a small nation could not be divided against itself and continue to exist.

He was the man who wove multiculturalism into the very DNA of Singapore, in the conviction that a small nation could not be divided against itself and continue to exist.

“This is not a Malay nation, this is not a Chinese nation, this is not an Indian nation,” Mr Lee Kuan Yew declared in 1965, upon Singapore’s split from Malaysia due to irreconcilable differences over how society should be organised.

While Malaysia chose bumiputra dominance and communal politics, Singapore would be the model multicultural nation, unique in the region. “Everybody will have his place equal: Language, culture, religion,” he vowed.

Ever wearing the lenses of harsh reality, however, Mr Lee believed work ensuring racial harmony was never done.

Forty-five years later, Mr Lee made a rare intervention in Parliament in 2010 — having interrupted his physiotherapy session — to bring what he felt was a needed reality check to those arguing for equal treatment for all races.

This premise was “false and flawed”, said the Minister Mentor, pointing to Article 152 of the Constitution, which makes it the Government’s responsibility to “constantly care for the interests of the racial and religious minorities” — in particular recognising the special position of the Malays as “the indigenous people of Singapore”. It would “take decades, if not centuries”, he added, for Singapore to reach a point where all races could be treated equally.

What some did not understand was that, for Mr Lee, multiculturalism was the only way to ensure Singapore’s survival — but it would ever be a work in progress, an aspiration not to be confused with an ideology of race-blindness, because the facts of reality pulled in the opposite direction. That was the paradox Singapore had to grapple with.

FOUNDATIONS FOR HARMONY

In the initial years of Independence, many people advocated catering to the racial majority in Singapore. But Mr Lee and his team refused, having made clear from the start: “One thing we should not do is to try and stifle the other man’s culture, his language, his religion, because that is the surest way to bring him to abandon reason and rationality and stand by his heritage.”

The May 1969 racial riots, which spilled over to Singapore from Malaysia, leaving four dead, drove home the explosive nature of race relations. Mr Lee vowed that “whoever starts trouble we smack him down” — a zero-tolerance approach enforced over the decades.

Beyond this security dimension, multiculturalism would also distinguish Singapore to the world. “That’s what will stand out against all our neighbours,” he pointed out.

There would be equal basis for competition, with a meritocratic Civil Service leading the way, where ability, and not race, mattered.

Just as vital was the need to break up the racially-segregated housing enclaves that were a legacy from the British. “As part of our long-term plan to rebuild Singapore and re-house everybody, we decided to scatter and mix Malays, Chinese, Indians and all others alike and thus prevent them from congregating ... On resettlement, they would have to ballot for their new high-rise homes,” said Mr Lee, who grew up playing with the kids of Malay and Chinese fishermen from a nearby kampung.

But the Government soon found that when owners sold their flats and could buy resale flats of their choice, the enclaves re-formed. So, ethnic group ceilings were introduced in 1989. While this depressed prices for certain resale flats, Mr Lee wrote: “This is a small cost for achieving our larger objective of getting the races to intermingle.”

MOSQUE BUILDING

When it came to Singaporean Malays’ beliefs, nonetheless, special sensitivity was shown. A 1994 interview revealed the pragmatism of Mr Lee’s thinking. “You cannot have too many distinct components and be one nation,” he said, “but there are circumstances where it is wise to leave things be … we put the Muslims in a slightly different category because they are extremely sensitive about their customs, especially diet.

“In such matters one has to find a middle path between uniformity and a certain freedom to be somewhat different. I think it is wise to leave alone questions of fundamental beliefs and give time to sort matters out.”

When dilapidated small mosques (surau) built on state land had to be removed for redevelopment, Mr Lee proposed a plan to replace each surau with bigger, better mosques in every housing estate through contributions from the Malay-Muslim community.

Ex-Cabinet minister Othman Wok recalled: “He said he would instruct the Civil Service to prepare a circular for all Malay-Muslims working in the government service to donate voluntarily to the mosque building fund, and the deduction will be through CPF. That was a good idea. Readily, they gave 50 cents.”

This freed Singapore from the pressure that could be brought to bear if the mosques were bankrolled by the oil-rich Saudis, said Mr Lee in retrospect; it also “gave our Malays pride in building their mosques with their own funds”.

GROUP REPRESENTATION CONSTITUENCIES

One controversial measure to ensure minority representation was the Group Representation Constituency scheme, which Mr Lee pushed through in 1988.

He noted that where people in the 1950s and 1960s voted for the party regardless of candidates, once the PAP’s dominance was established and people expected it to be returned to power, they began voting for the MP. “They preferred one who empathised with them, spoke the same dialect or language, and was of the same race,” said Mr Lee.

“It was going to be difficult if not impossible for a Malay or Indian candidate to win against a Chinese candidate. To end up with a Parliament without Malay, Indian and other minority MPs would be damaging. We had to change the rules.” In addition, this would stymie Chinese chauvinist tendencies by any political party, he added.

SELF-HELP GROUPS

Another initiative that drew criticism was the formation of self-help groups.

Having found that, since the days of the British, a larger percentage of Malay students were consistently poorer in mathematics and sciences, Mr Lee decided the Government could not keep the differences in exam results secret.

“To have people believe all children were equal, whatever their race, and that equal opportunities would allow all to qualify for a place in a university, must lead to discontent. The less successful would believe the Government was not treating them equally,” he wrote.

In 1980, he roped in Malay community leaders “to tackle the problem of Malay underachievement”, leading to the first self-help group, Mendaki, in 1982.

But Deputy Prime Minister S Rajaratnam, who crafted the National Pledge, was opposed, fearing the move towards community-based self-help groups would strengthen communal pulls. Mr Lee wrote: “While I shared Raja’s ideal of a completely colour-blind policy, I had to face reality and produce results. From experience, we knew Chinese or Indian officials could not reach out to Malay parents and students in the way their own community leaders did.”

Over the years, Malay students’ achievements improved. Mendaki’s progress spurred the formation of the Singapore Indian Development Association in 1991 and the Chinese Development Assistance Council in 1992.

In another instance, Mr Lee’s refusal to spell out anything less than the “hard truth”, as he saw it, continued to draw flak in the last years of his life.

His remarks that Islamic piety stood in the way of Muslims integrating with other communities — made in his book Hard Truths To Keep Singapore Going, published in 2011 — upset many. Soon after, he issued a statement explaining that the comment was made two or three years earlier and that “ministers and MPs, both Malay and non-Malay, have since told me that Singapore Malays have indeed made special efforts to integrate with the other communities … and that my call is out of date.

“I stand corrected, but only just this instance! I hope that this trend will continue in the future.”

More in our Special Edition this afternoon (March 23).