The Big Read: In the war against fake news, public needs to get in the trenches

SINGAPORE — It was over dinner on an evening in December 2016 when a sales manager at a printing company decided that he must make a stand against online falsehoods.

Close-up of a lady reading the Fact Check Singapore facebook page while holding a mobile phone with the Confirm? website in the background. Photo illustration: Koh Mui Fong/TODAY

SINGAPORE — It was over dinner on an evening in December 2016 when a sales manager at a printing company decided that he must make a stand against online falsehoods.

His mother was talking about a fake news article online about Ai Takagi, editor of the now-defunct The Real Singapore, suffering a miscarriage while in jail. Having followed the case closely — Takagi had a miscarriage before she was sent to jail for 10 months in 2016 for publishing seditious articles — he was struck by how easily Singaporeans unwittingly believe what they read on the Internet.

The 32-year-old, who only wished to be known as Joseph, runs Facebook page Fact Check Singapore. “Fighting fake news is something every Singaporean should take responsibility for, as there is only so much the government can do,” he said. If he is doing a public service, why is he afraid of letting people know his name?

He is worried about trolls who would label “anyone with a single positive comment about the government as an IB”, in reference to the phrase “Internet brigade” popularly used to describe propagandists.

“Abuse from trolls (like these) deter people from dispelling fake news. It is this abuse that keeps the majority silent,” he added.

In Joseph’s case, it is a lonely journey: Apart from his immediate family and very close friends, no one else knows about his secret mission. Every week, he puts up one or two posts on the Facebook page to debunk falsehoods that have been circulating on websites or social media.

A typical fact-checking post takes him around an hour or two to complete. To date, he has put up about 100 posts since the inception of the page, which has garnered a modest following of 500 users over the past 15 months.

Like many countries, Singapore is deep in the trenches in the fight against online falsehoods. In the last two weeks, a committee made up by Members of Parliament conducted public hearings to listen to views and suggestions from a range of individuals and organisations on tackling the scourge.

While several witnesses spoke about the need for independent, ground-up initiatives to address the problem, such efforts — including Fact Check Singapore which was mentioned in one of the written representations — are few and far between here.

Instead, the fiercest battle over fake news in Singapore is waged between pro- and anti-government platforms: Partisan Facebook groups such as Fabrications about the PAP and Fabrications Led by Opposition Parties have sprung up to counter misinformation put up by sites such as States Times Review and All Singapore Stuff. However, observers point out that these groups serve as echo chambers and could polarise society further.

Joseph said: “The real danger are people in the middle who are (and will be) unwittingly influenced by fake news.”

He added: “The Government is not perfect, but people need to decide who to vote for, based on facts.”

In comparison, ground-up independent efforts in Ukraine and Indonesia, for example, have met with far greater success. For instance, StopFake.org, whose co-founder Ruslan Deynychenko was also in town earlier this month to give evidence at the public hearings, has about 53,400 followers on Facebook, 28,300 on YouTube, and 25,300 on Twitter. It is run by 30 full-time and part-time employees as well as volunteers who include journalists, translators and IT specialists.

Closer to home, civil society group Masyarakat Anti Fitnah Indonesia (Mafindo) has been actively engaged in the war against falsehoods, not just through its fact checking Facebook group, but through outreach and education efforts. Apart from fact checking, its team — comprising seven full-timers and more than 300 volunteers across 17 Indonesian cities — runs public education and literacy campaigns, holds talks, and collaborates on projects with journalists.

At the public hearings held by the Select Committee earlier this month, national security expert Shashi Jayakumar, for example, suggested setting up a group that uses “grassroots participation” to counter fake news. Similarly, military expert Michael Raska proposed an independent organisation which could inspect fake news sources —like what has been done in the Czech Republic.

Meanwhile, researchers Carol Soon and Shawn Goh cited Fact Check Singapore as an example, and stressed the importance of having ground-up fact checking efforts.

On Friday, Singapore media companies Mediacorp and SPH also called for the establishment of a fact checking body that can deal with deliberate online falsehoods in an independent and transparent manner.

For instance, this group, which may consist of representatives from academia, the legal community and civil society groups, could be given the mandate to identify the falsehoods and recommend appropriate remedial actions. Similar outfits have already been established in Australia, Europe and Japan. “The body should be appointed by and accountable to Parliament,” the Mediacorp representatives said at the public hearing.

GROUND-UP EFFORTS HERE

Apart from Fact Check Singapore, another ground-up project called confirm.sg is being run by Mr Gaurav Keerthi, 39. Its website features a series of quizzes on hot button issues, such as rail reliability and population issues, to help the public find out if what they read online about these matters is true, and correct their misperceptions.

Set up early last year, confirm.sg also has a Facebook page which has about 190 followers. Mr Keerthi, also founded dialectic.sg, a website which aims to promote debates on policy issues.

Speaking to TODAY, Mr Keerthi — who gave evidence at the public hearing on Friday — said he became “very concerned with filter bubbles and echo chambers after the outcomes of various elections (in the United States, the United Kingdom and the Philippines) in 2017”.

After observing “how unproductive the online conversations were on important issues because many voters could not separate fact from fiction”, Mr Keerthi decided to experiment with a “gamified tool” by building an online quiz game to “identify where these bubbles and chambers were”.

Explaining the concept behind his passion project, Mr Keerthi said: “Each quiz has just 10 questions, and can be done easily on a bus/train ride to school or work. When participants get an answer wrong, they will see the correct answer, an explanation, and also how many people in their demographic profile got the answer right or wrong.”

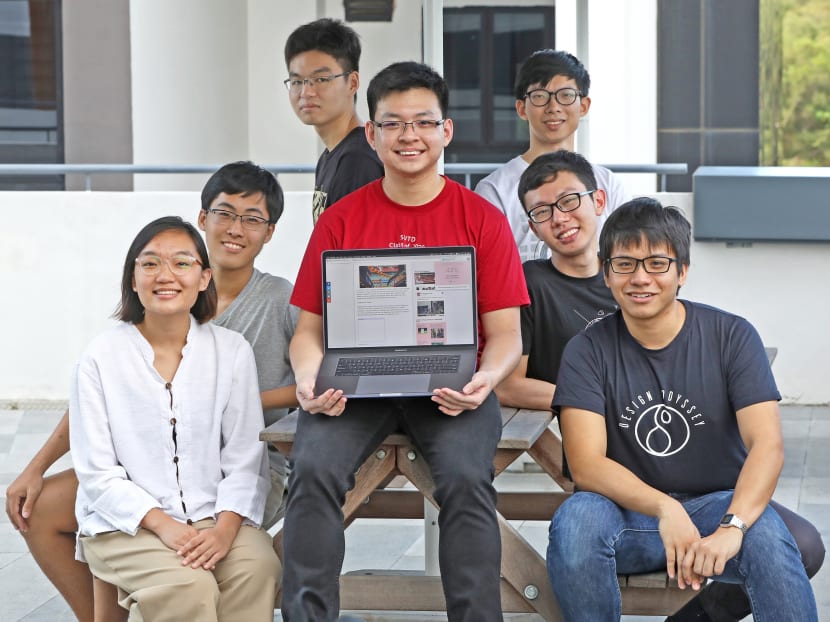

Elsewhere, a group of students from the Singapore University of Technology and Design (SUTD) has enlisted technology in the battle against fake news.

The team — which has three members currently: Mr Timothy Liu, Mr Tong Hui Kang, and Mr Brandon Ong, all 22 — has come up with an Internet browser extension prototype which can detect if an article contains falsehoods and flag them to the user.

This is done through machine-learning algorithms, paired together with crowdsourced information from a Reddit-style forum, Mr Liu told TODAY.

The prototype was borne from a hackathon organised last year by the SUTD, together with the National University of Singapore (NUS), the Media Literacy Council, and Google. It is undergoing tests and will be rolled out subsequently as a Google Chrome browser extension.

NUS media students will be the first pool of users and they will double up as trained volunteers in managing the crowdsourcing forum.

CHALLENGES

The SUTD team said a challenge which they faced in their project was in identifying which types of fake news to target. They settled on a general approach — choosing to tackle hoaxes, such as the fake news about Punggol Waterway Terraces’ roof collapsing, as well as other articles that could inflame tensions among its reader.

Said Mr Liu: “There is no silver bullet to tackle the problem of fake news. It is simple to suggest…(that) artificial intelligence (can) tackle (it), but the state of natural language understanding mechanisms...has not been developed to a point where they can perform robust fact-checking.”

In deciding what fake news to tackle, Joseph from Fact Check Singapore trawls social media and looks at what is trending. For example, in a recent post on its Facebook page, he made a side-by-side comparison between Thaipusam and St Patrick’s Day.

The police had said earlier this month that it granted a permit for a St Patrick’s Day procession without any restrictions on the playing of musical instruments, on the basis that the festival is celebrated in Singapore as a “secular, cultural event”.

But it drew discussion on social media, with some comparing it to Thaipusam, which up to recently, was subject to a ban on live music instruments.

On his experience so far, Joseph said that on some occasions, he has been attacked online by people who felt his posts were “pro-government”.

Like Joseph, Mr Keerthi finds it a challenge to ramp up his project to reach a wider audience due to a lack of resources.

Said Mr Keerthi: “As a non-profit self-funded project, I do not have the means to scale the project to reach as many people as I would like.”

It is also difficult to find independent sources of facts in some areas, he noted. “Even then, some facts are contested even by experts. Nevertheless, just because the task is difficult does not mean I should not persist,” he said.

THE FIGHT ELSEWHERE

In contrast, ground-up initiatives to combat online falsehoods in other countries have found it relatively easier to get funds and other resources to expand their operations.

The groups behind some of the efforts told TODAY that it was important that they do not receive any funding or support from their respective governments or partisan groups.

Stopfake, for example, is funded through crowdfunding and private donations, and supported by the International Renaissance Foundation, the Foreign Ministry of the Czech Republic, the British Embassy in Ukraine and the Sigrid Rausing Trust.

Apart from outreach via its website, the organisation, which was created in 2014 by alumni of the Kyiv-Mohyla School of Journalism, also records weekly television programmes and radio podcasts in English, Russian and Ukrainian, and produces a newspaper.

Borne out of adversity, the website began as a call to “protect the country”, after Ukraine was thrown into chaos by the ouster of its pro-Russia president Viktor Yanukovych.

About a week before StopFake’s establishment, Mr Yanukovych was ousted amid protests against his decision not forge closer ties with the European Union.

Russian intelligence agency, the GRU, seized on the uproar to launch a covert propaganda offensive against the new government, paving the way for the Russian military action, which led to the annexation of Crimea.

“The government had escaped the country at that time, so people, volunteers in different spheres started (asking), what can we do to protect our country?” Mr Denynchenko told reporters last week.

In Indonesia, the movement to fight fake news has gone beyond the online realm.

Mafindo founder Septiaji Eko Nugroho, 40, said the organisation began as a Facebook group called Forum Anti Fitnah Hasut dan Hoax about three years ago, and brought together a group of “sporadic hoaxbusters”.

“We don’t take funding from Indonesian government, also (not) from institutions that are perceived to be partisan… We accept funding that won’t interfere our independence and neutrality,” said Mr Nugroho, without elaborating.

He noted that Singapore has a high literacy rate, compared to his country, so the challenge ahead would be “(building) trust between people from different political views, ethnicities and religions”, while formulating laws that do not impede on the freedom of speech.

He also pointed out the need for public involvement in Singapore in the fight against fake news. For example, he suggested building a database of anti-falsehoods. “Who will build this database, and who will join to fact-check these issues?” he said.

CITIZENRY EFFORTS NEEDED: EXPERTS

Media experts TODAY spoke to noted current efforts in combating falsehoods are largely top-down, and there is room for more ground-up initiatives.

Professor Lim Sun Sun, who heads SUTD’s Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences cluster, said the Government and the relevant authorities or corporations have been swift in dispelling falsehoods when they appear.

She cited examples such as the online hoax of plastic rice being sold in supermarkets, and other food scares. “I don’t feel that the public feels that there is an overwhelming sense of desperation, or lack of guidance,” Prof Lim said.

And while there have been cases in Singapore of inflammatory comments made by certain individuals, Prof Lim noted that the authorities — such as the police — have been quick in their “interventions”.

Agreeing, Dr Soon, who is from the Institute of Policy Studies, said that as a result, “people (in Singapore) may not feel a compelling need to step up”.

She added: “Furthermore, and this is evident in other governance issues as well, there is a general reliance among the public on the Government to fix problems.”

She cited a survey last year where more than 90 per cent of Singaporeans supported stronger laws in tackling fake news.

Other experts pointed out that fact checking was a resource intensive process, requiring people to dedicate time and energy to trace the origins of hoaxes and verify information.

“I don’t think, hitherto, any civil society in SIngapore has either the inclination, or the bandwidth, or the resources, to do this,” Prof Lim said.

Nevertheless, Professor Ang Peng Hwa from Nanyang Technological University’s (NTU) Wee Kim Wee School of Communication and Information stressed that there is always room for a bottom-up approach to fighting fake news.

“If the Government declares that (something) is fake news...it can be problematic if it concerns... the framing of issues or opinions, as opposed to rhetorical fact,” said Prof Ang.

“So although the Government may be correct (in what it says), there is (and will be) scepticism among certain quarters, and it raises the question of trust in the Government,” he added.

Thus, there is a need for an “independent body” to build that trust, he reiterated.

In her submissions to the Select Committee, Dr Soon said that non-government fact checking initiatives play “an important role...especially during times of crises or periods where trust in the Government is low”.

Professor Mohan Dutta, who heads the NUS’ Communications and New Media programme, noted that in a top-down framework, the “paternalistic” underlying assumption is that “citizens are gullible and they don’t have the capacity to critically evaluate information”.

Nevertheless, he felt that ground-up efforts need to be “supported by states” and steeped in “critical literacy” — being able to “examine claims, consider and evaluate evidence, and situate the evidence within the considerations of power and control”.

Said Prof Dutta: “(Such efforts) would begin with a commitment to citizen voice and capacity for democratic participation. The question needed to be addressed is ‘How we can we equip citizens to participate as rational stakeholders, engaged collectively in making decisions that uphold the wellbeing of individuals, families, communities, and larger societies?’”

Prof Lim reiterated that initiatives by the citizenry are valuable. “Ultimately there is an educational value to it. It can educate and galvanise the broader public and give everyone a sense of shared ownership of the issue,” she said.

Agreeing, Mr Liu from the SUTD team working on the Internet browser extension prototype said that public education should always be the “first line of defence”, as it was not always possible for any... system to pre-empt and catch misinformation”.

Dr Soon believes that for ground-up efforts to take root here, the public needs to be ready for “different types of sites, even if they are partisan and practise selective debunking”.

‘VOLUNTEERS PLEASE’

For platforms like Fact Check Singapore and confirm.sg, it boils down to a question of resources.

“Many of us do this because we are optimistic and passionate,” said Mr Keerthi. “The best way to encourage and sustain these initiatives is to publicise them and help them grow, so that other young people will also feel inspired to build even better projects in the future.”

Having taken time off to learn data analytics, Mr Keerthi said he plans to improve the visualisations and analysis his website. “I plan to release interesting findings about the demographic patterns observed in the incorrect answers (if any). That is, do certain types of people all believe the same inaccurate information? Once we know that, we can help educate them or catch the online falsehoods that are being spread in that community,” he added.

Meanwhile, Joseph is adamant about not receiving external funding.

“Of course, I wish I can be paid (for what I do), but the source (of the funding) may (skew) your perspective,” he said.

He hopes that more Singaporeans will come forward on a voluntary basis to join the battle against online falsehoods.

He aims to grow his Facebook page following by as much as ten-fold, but he would require a group of dedicated volunteers to help in the fact checking.

He said: “It is my hope that Singaporeans can become more discerning of what they read online, and that malicious sites get shut down. Once that happens, pages (like mine) will not need to exist at all.”

Until then, he will soldier on in his one-man crusade.