Cancer scientists sniff out durian genome

SINGAPORE — A low-sugar version of the king of fruits that is suitable for diabetics could become a reality in the future, according to cancer scientists in Singapore who have mapped the genetic make-up of the durian for the first time.

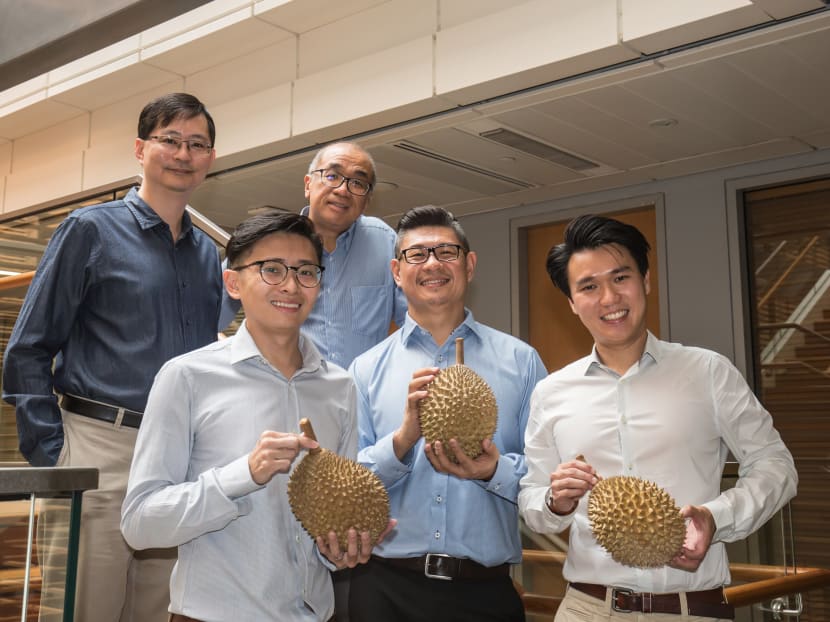

The scientists from National Cancer Centre Singapore and Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore. From Left to Right (Top Row): Prof Patrick Tan, Prof Teh Bin Tean. Photo: Duke-NUS Medical School & National Cancer Centre Singapore

SINGAPORE — A low-sugar version of the king of fruits that is suitable for diabetics could become a reality in the future, according to cancer scientists in Singapore who have mapped the genetic make-up of the durian for the first time.

Sharing the findings of the three-year research on Monday (Oct 9), the team of durian-loving scientists from the National Cancer Centre Singapore and Duke-NUS Medical School said with specific genes identified for various features of durians, odourless or milder tasting durians are possible in future.

The research could also lead to the discovery of medicinal properties of the fruit, the researchers added.

Driven by a “strong scientific curiosity”, the five-man team mapped out the genetic data of the Musang King (commonly known as the ‘Mao Shan Wang’) variety over and above their day jobs in cancer research.

The findings will be published in the academic journal Nature Genetics and the team has donated the data collected to the National Parks Board.

New genetic sequencing technologies allowed the team to study complex genomes, such as that of plants. The technologies led the team, which “did not have a track record in plant biology to now become fairly competitive in that area”, said Professor Patrick Tan, the co-lead author of the study.

Previous research on the durian had largely focused on creating new hybrids or the various chemical compounds in the fruit, he said.

The researchers identified the genes responsible for the fruit’s notorious smell – a class of genes known as methionine gamma lyases (MGLs) that regulate production of volatile sulphur compounds.

The durians were found to have four copies of the genes — twice that of cotton, and four times that of cacao, grapes or rice. This might give the durian plant an advantage in attracting animals to eat its fruit and disperse its seeds, said the researchers.

The cotton plant was found to be the durian’s closest relative and the cacao plant was found to be the durian’s ancestor. The study, which involved some 50 durians and around S$500,000 in donations from anonymous private donors, also found durian has twice the amount of genes — at around 46,000 genes — that humans possess.

Methods that the team used to “assemble” the genetic map of the durian included long-reads sequencing (to read longer genetic data) coupled with short-reads sequencing, and technology to link all the genomic information.

Technology used to map the durian’s genetic data could be applied to other plants or herbs with medicinal value, said the team.

Apart from the possibility of cultivating new varieties of durians — with traits that can be modified — the team said the genome sequence can help in identifying genes involved in disease resistance, drought tolerance and flavour profiles.

Technology could speed up the process taken to cultivate varieties of durians that possess favourable traits, said Mr Cedric Ng, senior research associate at the Laboratory of Cancer Epigenomics at the National Cancer Centre Singapore.

For the Musang King variety, agricultural growers traditionally take around 20 to 30 years to cultivate the durians with good qualities through breeding and selection, but technology can reduce that to around five years, he said.

“There is so much wealth of biodiversity in Asia. We started off our work with Asian cancers, but it’s really about what makes living in this part of the world so unique,” said Prof Tan. “We felt that this was a great opportunity to contribute to the world body of knowledge in a way that would be more difficult if you were in the United States or Europe.”