Education reform: The Hong Kong experience

In 2000, Hong Kong overhauled its education system. Among other things, it tweaked its Primary 1 admission scheme to increase the proportion of places allocated for children living near the schools, abolished national exams at Primary 6, and pushed for through-train schools that provide a direct pathway from the primary to secondary level. Instead of three national exams previously, students in Hong Kong now sit for just one, at 18 years old.

In 2000, Hong Kong overhauled its education system. Among other things, it tweaked its Primary 1 admission scheme to increase the proportion of places allocated for children living near the schools, abolished national exams at Primary 6, and pushed for through-train schools that provide a direct pathway from the primary to secondary level. Instead of three national exams previously, students in Hong Kong now sit for just one, at 18 years old.

As Singapore mulls over its own set of education reforms announced during last month’s National Day Rally, TODAY looks at Hong Kong’s reform experience and the impact on educators, parents and students in a two-part report. In the first instalment, we examine the changes in the Primary School system.

HONG KONG — On Nathan Road, a busy shopping strip, advertisements of “star tutors” promising stellar results vie for eyeballs alongside colourful billboards for electronics and fashion goods. In Wan Chai district, known among locals for its cluster of top public schools, tuition classes are held throughout the week in nondescript shophouses. Clearly, people in Hong Kong are serious about education. And in a bid to, among other things, reduce the examination-driven learning culture and the stress in schools, the authorities rolled out comprehensive reforms from 2000 to overhaul the education system from top to bottom, with measures for pre-schools right up to universities.

A reform committee that was set up noted, in its report, that pupils are not given comprehensive learning experiences to encourage creativity, among other issues. It added that there is a need to “uproot outdated ideology and develop a new education system that is student-focused”.

Following the report, the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region government tweaked the Primary 1 admissions scheme. It also abolished the national exams at Pri 6. Some primary schools also linked up with secondary schools to provide a through-train, 12-year programme.

More than a decade on, the impact of the reforms has been a mixed bag, according to interviews with educators, academics, parents and students.

Some welcomed the liberation from an exam-driven academic culture, while others said there is still a lot of stress in schools — not only for parents and students but the educators as well. In the absence of a primary school leaving exam, schools have to administer internal tests — or what some educators dubbed “accountability” tests — at Pri 3 and Pri 6. Educators fear that schools where students do badly in these assessments risk being shut down by the government as Hong Kong grapples with a falling student population due to the low birth rates.

Nevertheless, Professor Cheng Kai-ming, one of the forerunners of the education reforms, said the revamp has been “successful”.

“The results will take a much longer time to be appreciated, and people may not appreciate (them), because they live in different generations and have no comparison,” he added. “The reform is more about the nature of school education, rather than its achievements”.

The former educator, who is currently Chair of Education at the University of Hong Kong (HKU), said the necessary ingredients are in place, including having a ground-up school management system where there is flexibility and autonomy for teachers. “I am optimistic,” he said.

A MORE EQUITABLE P1 ALLOCATION SYSTEM — OR NOT

Ms Louisa Tang, a former primary school principal, said that before the reforms, school leaders had great autonomy in deciding which students to admit. They had the final word on up to 65 per cent of Pri 1 places. The remaining places were then allocated randomly by a centralised process, typically to families living in the school’s vicinity.

Ms Tang, who retired recently after 40 years in education, said: “There were some benefits in (the past) arrangement as principals could select students to boost the school’s performance. This created diversity and spurred innovation in the school sector.”

But she noted that the practice had caused anxiety among parents, many of whom tried hard to impress school leaders with their children’s portfolio and interview skills.

Under the reforms, the quota of centrally allocated school places was increased from 35 per cent to 50 per cent. The rest of the places are distributed using a point system: Priority is given to siblings studying in the same school or parents who are working there. Consideration is also given to parents who are alumni of the school and whether the child is a first-born, among other factors.

Educators and parents in general welcomed the new admissions system, which they said is more equitable. A parent, Ms Isabel Chan, 41, said that centrally allocating half of Pri 1 places made it easier for children without any links to enrol in schools near to their homes.

The popular Baptist Lui Ming Choi Primary School (Sha Tin) draws about 300 applications for 120 Pri 1 places each year. Its principal Linly Wong said the current system is not only “fairer, to some extent” but it also helped to prevent young children from having to travel long distances to get to school.

According to a Hong Kong Education Bureau report last year, more than half of the parents who opted for schools in their housing district were allocated places for their children in their first choice of primary school.

However, the allocation system has also resulted in parents buying houses near their preferred schools, especially in areas such as Sha Tin and Wan Chai, where locals claim that there is a higher concentration of popular schools.

NO NATIONAL EXAM, NO STRESS?

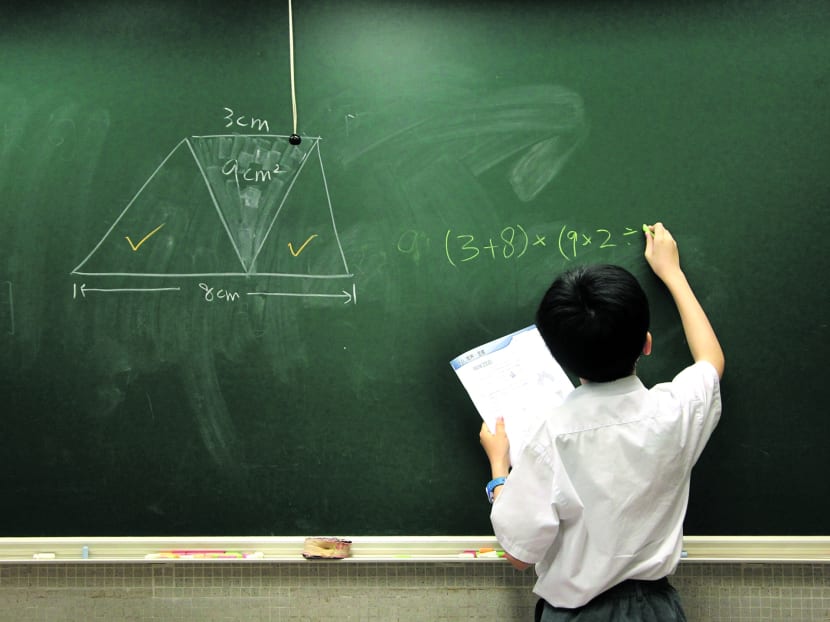

Like in Singapore, 12-year-olds used to sit for a national exam known as the Academic Aptitude Test (AAT). Based on their results and how they fared in school assessments, students were categorised under five bands. The banding system was then used to allocate secondary school places.

The AAT was scrapped and the number of bands reduced to three.

In tandem with the government’s move to provide nine years of universal basic education, the education reform committee felt that “there is no genuine need for a highly selective school place allocation system” for 12-year-olds. Instead, admission to secondary schools was based on students’ results at year-end internal school exams at Pri 5, and the mid-year and year-end exams at Pri 6.

Under the old system, how well a school’s entire cohort of Pri 6 students performs will affect the banding of the individual student.

Using an analogy, Prof Cheng said that previously, primary school education was a tiresome, six-year cycle geared towards an all-important finale. “Running a 600-metre race is different from running a 6x100-metre race,” he quipped.

Without the need to prepare students for the AAT, schools are able to focus on holistic development.

Baptist Lui Ming Choi Primary, for example, incorporated environmental education for its pupils. At Shap Pat Heung Rural Committee Kung Yik She Primary, educators tapped government funds to build music rooms and television studios.

Said retired primary school educator Ms Tang: “There is now less pressure and schools are liberated to conduct other activities. Primary school education has been transformed.”

Between 2007 and last year, student enrolment in Hong Kong fell from about 386,000 to 317,000. Over the same period, the number of primary schools decreased from 631 to 569.

Apart from the pressure on schools to make sure their students do well in “accountability” tests — which are monitored by the government — the fact that results of school-based tests at the Upper Primary levels are taken into consideration for secondary school admissions meant that the stress could never really go away, despite the abolishment of national exams at Pri 6, parents and educators said.

Also, secondary schools can set aside 30 per cent of places for discretionary admissions based on, for example, a student’s grades or non-academic talents. Joshua Wong, 11, who attends tuition once a week, knows the importance of doing well - and has set his sights on enrolling in the prestigious Queen’s College. “Only with good results, will I be able to enrol in a good secondary school,” he said.

THE TROUBLE WITH THROUGH-TRAIN

In Singapore, the idea of “through-train” schools has been repeatedly raised in Parliament. For example, Moulmein-Kallang GRC Member of Parliament (MP) Denise Phua has suggested a direct pathway from pre-schools all the way to secondary schools, while Non-Constituency MP Yee Jenn Jong and Nominated MP Laurence Lien have proposed a through-train model from primary to secondary level.

As part of the education reforms in Hong Kong, the government encouraged primary and secondary schools with the same education philosophy to collaborate on a voluntary basis, including to the extent that pupils in a primary school will be given automatic admission to a paired secondary school. The idea is to “provide students with a coherent learning experience”, in the words of the education reform committee.

At present, there are 18 pairs of public primary and secondary schools offering through-train programmes. Direct subsidy schools in Hong Kong, similar to the independent schools here, have also set up such pathways in recent years. Educators of through-train schools said that the benefits include being able to coordinate curriculum across primary and secondary levels to avoid overlap and a smoother transition for pupils.

But they pointed out that with automatic entry into secondary schools, there were potential pitfalls such as having to manage greater diversity in the classroom. Tung Chung Catholic School (Primary) Principal Fung Lap Wing added: “With a direct pathway to Secondary 1, some students would be less driven in their studies.”

Ms Ko Wai Kuen, Principal of Fukien Secondary School Affiliated School, said such an alternative model provided greater room for non-academic pursuits such as project work or learning about Chinese classics.

However, she noted that secondary schools would still be under pressure to maintain its academic standing. And while primary school students are only required to pass their subjects, the teachers will have to ensure that the pupils are not lagging too far behind, she said.

These sentiments were reflected in a recent Hong Kong Education Bureau study on the “through-train” model, where secondary schools cited the challenge of having to admit all students — who come with varying levels of learning ability — from affiliated primary schools.

The committee which carried out the study recommended more resources to help teachers coordinate curriculum and pastoral care matters. It also proposed more flexibility in secondary school admission, including allowing schools to reject a student if he or she continues to perform unsatisfactorily.

On Monday, TODAY looks at the impact of the education reforms on Hong Kong secondary schools, including how banding has resulted in stigmatisation of some schools and their pupils.