SMEs need competition, not just subsidies

The fate of wages is linked to the structure of our economy.

The fate of wages is linked to the structure of our economy.

Ninety-nine per cent of firms in Singapore are small and medium enterprises (SMEs), while the remaining 1 per cent are large corporations, mostly foreign multinationals. About 70 per cent of our workforce are employed in SMEs.

But SMEs contribute only half of the annual value-added (a proxy for GDP), while large corporations make up the remaining 50 per cent.

This helps explains why wage growth in SMEs is so sticky upwards. Essentially, SMEs as a whole are not sufficiently value-adding to the economy to justify wage increases. The Government’s plan has focused on restructuring to change this around.

So, what is economic restructuring? The focus has been on productivity and innovation. We hear these buzzwords incessantly whenever there is a discussion about economic policy.

Government grants and incentives are skewed towards helping firms boost their productivity and innovation. Such financial aid is often, as with the case with the Productivity and Innovation Credit (PIC), made very easy to access.

To aid lower-income workers while restructuring is in progress, the Government also supports the policy of wage supplementation. This is largely in the form of Workfare but also includes the Special Employment Credit (SEC) and the Wage Credit Scheme (WCS).

Beyond these special transfers to business and workers, there are a myriad benefit schemes available through SPRING, IE Singapore, the Skill Development Fund and Workforce Development Authority (among others) to assist firms and workers to restructure and upskill respectively.

Looking only at the transfers to businesses and Workfare alone — about S$1 billion per annum — the “bill” for restructuring is certainly not small. And it is growing.

IS RESTRUCTURING WORKING?

Nearly five years into the restructuring plan, the results are, at best, unclear. Multifactor productivity growth (MFP) is still negative (the extraordinarily positive number in 2010 was due to a bounce off a low GDP base in 2009 due to the sharply contracting economy).

However, the interesting — and potentially most promising — feature is the relationship between labour and capital inputs.

Before 2009, when restructuring measures such as the foreign worker levy increases were introduced, labour input had a greater share of contribution to the GDP than capital. Since 2009, this relationship has been inverted. This reflects a tight labour market but not necessarily greater capital investments to drive productivity.

Unfortunately, annual GDP growth itself has been declining. Even an improvement in GDP performance year-on-year, from 1.3 per cent in 2012 to nearly 4 per cent last year, is little reason to cheer.

Only under three scenarios can we say conclusively that productivity improvements have occurred.

First, if GDP growth were to increase while labour and capital inputs remained at the same levels. Second, if GDP growth stayed the same but factor inputs from capital and labour declined. And third, if GDP rose or stayed the same while capital input remained the same but labour input declined.

In each case, the gap between the sum of capital and labour inputs and GDP growth would be explained by productivity improvements.

UNMASKING GROWTH

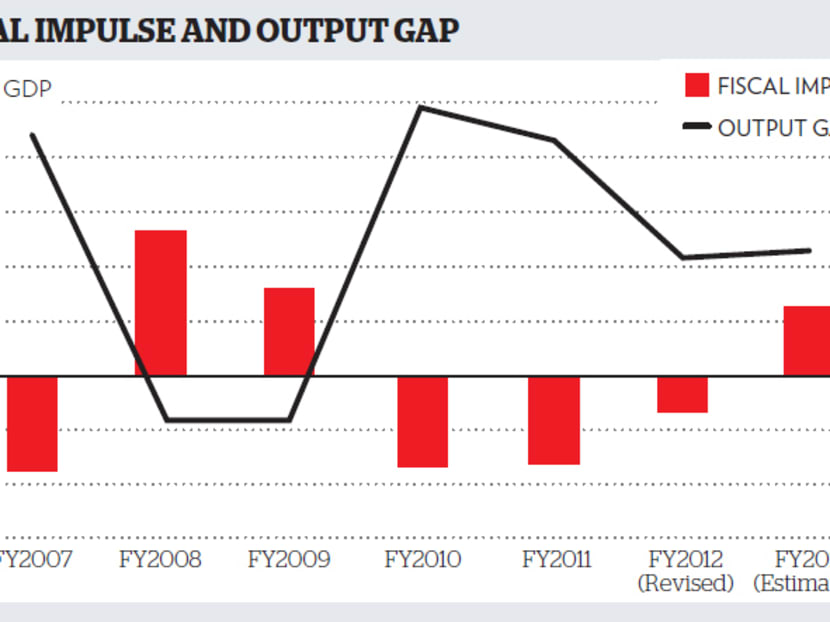

In the wake of strong public reaction to the effects of the rapid population expansion on the public infrastructure, the Government has embarked on large-scale public works projects ranging from transportation to housing and healthcare. These large-bill projects have created a positive fiscal impulse in the economy.

This boost is estimated to have contributed more than 1 per cent to GDP growth for FY2013. Thus, if FY2013 GDP growth is 4 per cent, then about 25 per cent to 30 per cent of that were contributed by public projects.

In past years, particularly in FY2008 and FY2009, the Government accelerated or added to public works to use fiscal impulse as an automatic stabiliser to a declining demand. However, our population-related infrastructure expansion is independent of economic conditions and protracted. So, we can expect to see a positive fiscal impulse for several years.

To get a sense of how the underlying real economy — which deals with trade, provision of goods and services — is doing, we need to strip out the fiscal impulse. By doing so, we unmask the data to reveal real economic growth — which is critical outcome data when evaluating whether we are making progress in the restructuring.

The output gap (see chart) shows how much we are performing relative to our economic potential.

The positive output gap shows that we are exceeding potential, in part due to the large infrastructure projects, but also because the economy is growing under conditions of constraint — including policy-induced labour tightening.

While it is generally good to exceed potential, there can be consequences in terms of inflationary pressures. The main problem for our economy is that we have a high positive output gap at low positive GDP growth levels. This suggests that we are still struggling to find strong drivers for real growth and to find macro-efficiencies to lean out our costs of production.

COMPETITION, NOT COMPETITIVENESS

The focus on productivity and innovation for firms to become more competitive is valid.

However, the emphasis on government subsidies as a way to drive these needed improvements is well-intentioned — but inadequate.

The most effective driver of improvements in productivity and innovation is competition.

It is competition that selects between the competitive and the rest. The notion of “competitiveness” has meaning only when contingent on having strong competition. We have to focus on how to induce more competition in sectors with poor productivity. If we do not, then the provision of generous grants and subsidies may well be making our firms less, not more, competitive.

By focusing on increasing competition as a first-order priority, we can expect competitiveness to become a natural survival response by most of our firms. We can induce competition with several novel steps.

First, we could encourage the participation of select, highly productive foreign firms in a range of our economic sectors, particularly those with low productivity.

Second, industry associations could work to encourage demand-side firms to aggregate demand, thus forcing consolidation in supply chains. Upsizing through consolidation would give surviving firms the critical production base to justify larger capital investments.

Third, the Government could introduce a variable policy rather than a general policy approach. In a variable policy model, incentives and other benefits could be withheld from persistently under-performing sectors, such as construction, to allow the full effects of economic competition to be felt by firms.

SHOW PROOF FIRST, THEN GET INCENTIVES

Fourth, the Government could require the award of incentives and other benefits — now almost automatic — to be conditional upon retrospective proof of improvements. In other words, firms would have to make the investments first, achieve measurable results and only then apply and expect to receive transfers from the Government.

Fifth, government procurement practices for large orders could also be adjusted to insist that tendering firms provide proof of their productivity. This would incentivise firms to compete on levels other than merely price.

Sixth, while the Government is already doing much to promote promising local start-ups, it could also explore how to enlarge the pool of venture capitalists (VCs).

This would involve bringing local start-ups to the notice of international VCs, encouraging more foreign VCs to have a local presence and making it conducive for more locals with expertise and capital to play a VC role. Our sovereign wealth funds, such as Temasek, could be encouraged to play such a role.

Seventh, more of our SMEs need to expose themselves to international competition. There are natural limits to growth in an economy with a small domestic sector.

The Government’s efforts through SPRING and IE Singapore are laudable. But it is down to leaders of firms to leave their comfort zones. It is ultimately only by expanding into overseas markets that our SMEs will be able to shift their production frontiers.

FACE DEMONS OF CHANGE

Some of these measures would involve administrative burdens for both firms and the Government. However, the sums involved in the annual transfers are sufficiently large and the policy goal sufficiently critical as to justify the additional costs.

The search for productivity is neither straight nor a short path. But it is a mission-critical path to take if we are to achieve the multidimensional goals of pursuing growth, creating sufficient good jobs for Singaporeans and lifting wages in a supportable way over the longer term.

It is an unfortunate reality that we have to face the demons of change first, before we can expect to meet the angels bearing benefits only much later down the path.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Devadas Krishnadas is Managing Director of Future-Moves, a strategic risk consultancy. His book, Sensing Singapore: Reflections in a Time of Change, was released in January.

*For Part 1 of this look ahead to Budget 2014 — Is trickle-down economics working for S’pore? — go to tdy.sg/comeconomics14feb.