Why Najib is stepping up engagement of China

Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak’s official visit to China last week was his third since he took power in 2009. Yet it generated more publicity and debate in and outside Malaysia than any of the others, for several reasons.

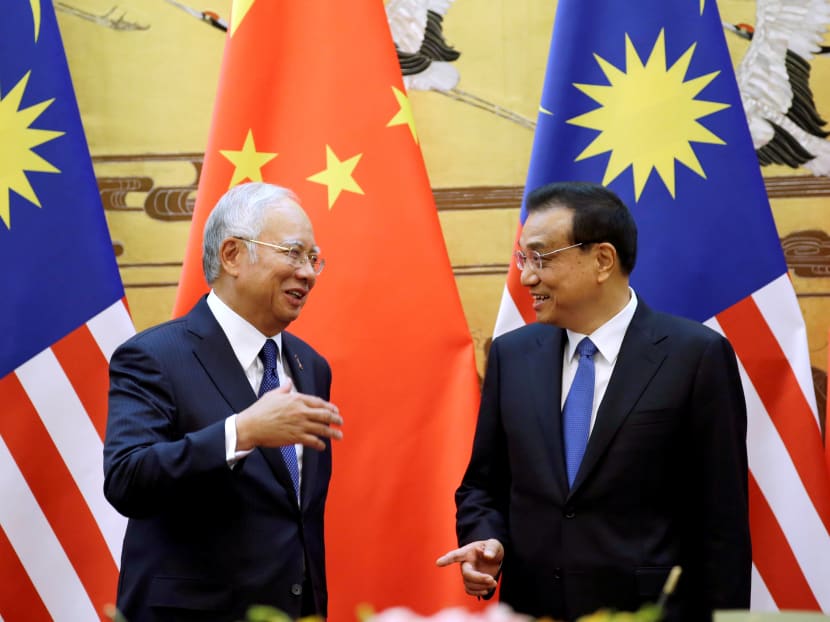

Malaysia's Prime Minister Najib Razak and China's Premier Li Keqiang attend a signing ceremony at the Great Hall of the People, in Beijing, China, November 1, 2016. Photo: Reuters

Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak’s official visit to China last week was his third since he took power in 2009. Yet it generated more publicity and debate in and outside Malaysia than any of the others, for several reasons.

First, the visit had a clear economic purpose. But looking to China is not new in Malaysia’s foreign trade policy. After Malaysia became the first ASEAN country to establish diplomatic relations with China in 1974 - under Mr Najib’s father, former prime minister Tun Abdul Razak Hussein - trade missions to China have become a mainstay in Malaysia’s foreign policy. This was especially the case during the premiership of Dr Mahathir Mohamad.

While the primacy of economics is unremarkable, what was striking about Mr Najib’s visit was the sheer size of the trade and investment pacts signed by both sides. The 14 business agreements and Memorandums of Understanding inked were worth RM144 billion, the highest on record, underscoring the deepening economic engagement between Malaysia and China.

Second, the trip has to be viewed in the context of the arbitral tribunal award in July which dismissed most of China’s claims in the South China Sea. In the wake of the ruling, Beijing has been eager to widen its network of support in Southeast Asia. Malaysia, as a claimant state, is also keen to dial down tensions in the disputed waters. During Mr Najib’s visit, both sides called for a peaceful resolution of the territorial disputes, and noted that “intervention” by external parties will not help resolve the issue, in what appeared to be a veiled reference to the US.

Third, the visit signified a strategic turning point towards closer naval cooperation between Malaysia and China with the purchase of four Chinese naval vessels by Putrajaya. Given that Malaysia has traditionally purchased Western naval equipment, the latest deal has fuelled speculation of a geopolitical shift in Malaysia’s defence policy from Washington to Beijing.

Such talk is premature for two main reasons. One, defence procurement is not a zero-sum game, and there is merit in diversification. A single defence deal with Beijing does not signal a turnaround in policy and cooperation with others, including Washington. Mr Najib is cognisant of this fact as he was Malaysia’s Defence Minister for 14 years. Two, this defence deal does not come at the expense of Malaysia ceding its claims in the South China Sea. Bintulu in Sarawak, for example, is being beefed up as a new naval base to protect nearby waters, islands and oil reserves.

Fourth, Mr Najib’s veiled attack on the West in a Chinese editorial during his China trip was particularly instructive as snide remarks about the West were traditionally synonymous with Dr Mahathir. Although not as caustic as Dr Mahathir, Mr Najib’s point about how Western powers should not ‘lecture countries they once exploited on how to conduct their own internal affairs’ prompted a senior US official to regard Mr Najib’s statement as ‘a little bit more like Mahathir.’

Mr Najib’s viewpoint can be explained in two ways. One is his belief that he is speaking not just for Malaysia, but also other countries belonging to the developing world, including China.

Being a spokesman for the developing world has been a longstanding plank of Malaysia’s foreign policy, especially under the premiership of Dr Mahathir. This is akin to the country assuming the status of a middle power, as Mr Najib himself said in a speech to Malaysian envoys in February 2014.

Mr Najib could also be venting his frustration at agencies in the US implicating him in the 1MDB scandal, which the Najib administration regards as interfering in Malaysia’s internal affairs.

Taken together, Mr Najib’s China trip is indicative of Malaysia performing a triple-balancing act in foreign policy.

The first is balancing between extracting as much economic benefits from China as possible and not being dragged into a Chinese-dominated order, which is not domestically acceptable to the majority Malays, chiefly those with ultraconservative stripes who remain apprehensive of the Malaysian Chinese.

The second is balancing between closer naval cooperation with China and protecting its own claims in the South China Sea as a matter of national pride, state sovereignty, and territorial integrity.

The third is balancing between engaging China and keeping relations with other countries, especially the US, on an even keel.

This practice of triple balancing is consonant with Malaysia’s national interest as it pertains to economics and security.

This counters the critics who believe Mr Najib has ‘sold’ Malaysia to China. In fact, it is in the national interest of Malaysia to engage China in its foreign policy, as evidenced, for example, by the raft of bilateral pacts signed during the prime minister’s latest China visit.

For Mr Najib too, Malaysia’s national interest is congruent with the interest of his UMNO-led Barisan Nasional coalition to continue governing the country. Trade and investment, including from China, pouring into Malaysia will be significant at a time when Mr Najib requires a further boost in the economy to enhance his legitimacy to govern the country. A sustainable growing economy will be a crucial determinant as to when Mr Najib will hold elections, due in 2018, and also augmenting the chances of his coalition being re-elected to government.

Mr Najib’s father, Tun Razak, played the China card to bolster the chances of his political coalition winning the 1974 elections, particularly after the coalition lost two-thirds majority in parliament post-1969 elections. Similarly, Mr Najib is anticipating the same outcome in the not-too-distant elections for his coalition to return to government under his leadership.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Dr Mustafa Izzuddin is Fellow at ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute.