The Big Read: Beset with problems and losing its capital status, Jakarta still a city of dreams for many

JAKARTA — Despite Jakarta's well-documented multitude of problems — from notorious traffic jams, clean-water crisis to choking pollution — millions of Indonesians from all over the sprawling archipelago still flock to the capital with hopes of finding the proverbial pot of gold at the end of the rainbow. Will things change for better or worse when Jakarta loses its capital city status?

A typical Car-Free Day in Jakarta, which closes off the capital’s main roads, will see hordes of residents flocking to the streets.

JAKARTA — He calls it a “kost for jailbirds” — the six-square-metre shoebox unit in central Jakarta that Mr Appe Novian Caniago has been renting at 500,000 Indonesian rupiah (S$49) a month for the past three years.

A kost usually refers to a spare room which a landlord rents out but his unit, which is near one of the newly-opened MRT stations, is a makeshift version — erected with partition boards to house seven more rooms on the roof of a shophouse selling shoes and bags on the first floor.

The 48-year-old’s rooftop “cell” heats up like an oven in the day. Sometimes, fights break out with noisy neighbours as the walls are porous. And the common toilet and bath area he shares with the other tenants — including a couple with a young child — is so often choked that he had inscribed a warning in Bahasa Indonesia on the wall that says : “Don’t litter because if it is clogged, we will all be flooded. Be a little smart, okay?”

Despite his austere surroundings, the musician-turned-street busker is not going anywhere.

“I don’t need a comfy place. I just need a warm place that makes me want to wake up early to pursue my unfulfilled dreams,” said Mr Appe who left his hometown on Borneo island when he was 18 with high hopes of making it big as a singer-songwriter in Jakarta which sits on Java island, the centre of Indonesia's political and economic life.

“If you choose a more expensive kost, you are going to relax and wake up late. That’s not good. We are here for the struggle.”

Mr Appe’s story offers a glimpse into the enduring appeal of Jakarta, warts and all. Despite its well-documented multitude of problems — from notorious traffic jams, clean-water crisis to choking pollution — millions of Indonesians from all over the sprawling archipelago still flock to the capital with hopes of finding the proverbial pot of gold at the end of the rainbow.

More than just Indonesia’s administrative capital, the overpopulated city of Jakarta is the centre of the country’s economy, education institutions and culture.

Nicknamed the “Big Durian” after the pungent, spiky fruit that deeply divides fans and detractors, Jakarta has a population of about 10 million, translating to approximately 15,000 residents per sq km. In comparison, Singapore's population density is about 8,000 residents per sq km.

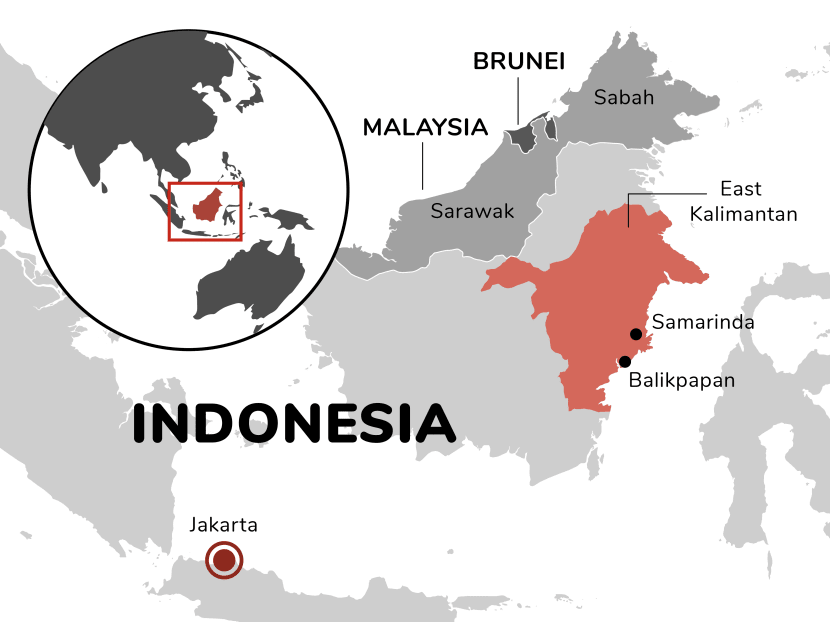

To ease the multifaceted burdens that a literally sinking Jakarta has had to bear for decades, Indonesian President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo announced on Aug 16 plans to move 1.5 million civil servants to a future capital city in East Kalimantan. The yet-to-be-named capital will be built on a 180,000-hectare space three times the size of Jakarta.

If everything goes as planned, the relocation may start as early as 2024, when Mr Jokowi’s second and last five-year term ends.

While the end may be in sight for Jakarta’s days as the country’s capital, Indonesian residents interviewed by TODAY believed it would not make much difference to their daily lives.

They felt that Jakarta will continue to play an important role, along with its many troubles, and complement the new capital — like New York to Washington DC, Brasilia to São Paulo, or Kuala Lumpur to Putrajaya.

And Jakarta residents like Mr Appe will continue to live in a kost downtown to avoid wasting time in traffic jams.

Others, like architecture student Masitha Nurul Fadhila Sekardini, will still have to factor in four to five hours’ of commuting time in their daily schedules.

UNENDING TRAFFIC NIGHTMARE

Twenty-year-old Masitha, who hails from Bekasi – Indonesia’s most populous satellite city on the eastern border of Jakarta — has to wake up at 5.30am for school at Binus University, which is more than 20km away. Any later, the crowd at Jatibening bus terminal would get out of hand, delaying her commute.

After school, she often chooses to wait out in the city past 7pm before journeying home.

Still, she often has to make five transits: An ojek (Indonesian for taxi bike) takes her from her campus in West Jakarta to Senayan. Then, a TransJakarta bus towards Dukuh Atas. Walk five to 10 minutes to Sudirman railway station, where she will board a train to Manggarai station. Next, a transfer train to Bekasi railway station and finally, another ojek to get to her doorstep.

A more direct way would be a bus that goes straight to Bekasi, but more often than not, commuters have to stand in a packed bus for two hours — not something that Ms Mashita is keen on doing after a long day at school.

“Yes, I am wasting time, but everyone struggles,” she said, pointing to older Jakartans who no longer bat an eyelid at being stuck in traffic day in day out.“The transport now is way nicer than before, so why complain?”

The MRT line that opened five months ago is not useful for Ms Mashita, since it serves only 13 stations from the centre of Jakarta towards the Southwestern region. The option is also more expensive, at between 3,000 rupiah (S$0.30) and 14,000 rupiah, depending on the number of stops travelled.

A bus ride would cost her 3,500 rupiah, and an inter-city train ride would cost 3,000 rupiah including transfers.

Commuters are not the only ones grappling with traffic woes; drivers do not have it easy either.

An “odd-even” policy — applied at major roads during rush hours from 6am to 9am and 4pm to 9pm on weekdays at the moment — regulates that cars with licence plates ending in odd numbers are only allowed on odd-numbered dates, while even licence plate holders can only travel on these roads on even-numbered dates.

But the lack of comfortable alternative transport options have led to drivers resorting to navigating narrow and windy roads referred to as “jalan tikus” – or rat streets – jamming up kampung areas beyond the main roads. And richer city dwellers are known to have two cars, one with an odd licence plate and the other even, to get around the regulation.

For Ms Erisca Saraswati, 27, sales and distribution manager at health insurance company Safe Meridian, travelling by “jalan tikus” two Fridays ago – an “even” day when her car’s plate is odd-numbered – would end up as a gruelling two-hour 35km journey if she sets off at 8pm, so she waited till past 9pm when the rule is lifted to start her journey.

It was frustrating for her as her destination was just 10km away, and would have taken her 30 minutes if she had used a straightforward route.

Even as a layman, Ms Erisca knows the root of Jakarta’s traffic problem: Private vehicles are relatively cheap that five members in a family can each afford to get their own cars or motorcycles.

Ms Erisca — whose four out of her five-member family drive — pointed out that it only took 500,000 rupiah to renew her expired vehicle registration certificate, and the same amount to pay for the downpayment of a bike.

Transportation expert Alvinsyah, who goes by one name, said Jakarta’s development had been overly focused on building highways for more than 40 years, while the pent-up demand for public transport remains unmet.

Jakarta’s population density is easily twice that of other South-east Asian cities such as Singapore, Kuala Lumpur and Bangkok.

But the Indonesian capital currently has only one MRT line with a daily ridership of 95,000, and a bus system serving some 600,000 passengers daily. The maths doesn’t add up, he said.

“(Highways) are easy to design, easy to build, and you just need a five-year construction period. After that, you just open the road. Don’t need to manage it like public transport,” said Mr Alvinsyah, who is part of the University of Indonesia’s transport research group.

But he stressed that highways are not a good solution.

The proven transport solution to manage the flow of commuters in metropolitan cities is still public transport, and it should ideally span the more than 6,000 square kilometres making up Greater Jakarta where 30 million live. The area comprises Jakarta, Bogor, Depok, Tangerang and Bekasi, collectively referred to by locals as “Jabodetabek”, which takes the first letters of each city.

How did Jakarta morph into “Jabodetabek”?

Mr Alvinsyah said the problem started 20 to 30 years ago when Jakarta started intense development and big developers dangled tempting land prices to vacate its residents. People who accepted the offers moved to the periphery.

The further away from central Jakarta, the cheaper the land cost, where some bought bigger plots and cars with their payouts, he pointed out.

“Everybody did the same thing, and you have a traffic problem,” Mr Alvinsyah said. “The growth never stops and cannot be stopped... Jakarta becomes like sugar to human ‘ants’ due to its centralised development.”

Urban transport activist Udayalaksmana Halim said transportation was practically relegated to the private sector in Jakarta until 2004, when the city’s first state-owned bus operator, TransJakarta, emerged.

Under TransJakarta, private operators were contracted and paid to run buses, eliminating the disruptive habit of bus drivers stopping at random spots to pick up more passengers in order to maximise income, he said. Its drivers now ply along 13 bus-exclusive corridors called busways.

The city’s elevated bus stations were built precisely to deter private buses from stopping anywhere they liked.

“The government was mainly in the business of giving and selling licences. They don’t care about fleet and operation,” said the 31-year-old former research and policy manager with the Institute for Transportation and Development, a non-governmental organisation. He recently joined TransJakarta, as head of its route management department.

The problem now is with integrating the different modes of transport, so riders can switch seamlessly between modes. “We still have ‘common enemies’, such as private cars, GoJek, Grab, and motorcycles, and the MRT cannot stand up against them alone,” he said. “We need integration.”

He added: “Everybody supports MRT because everyone wants everyone else to board the MRT, so the roads will be (freed for drivers).”

THAT SINKING FEELING IN MORE WAYS THAN ONE

Traffic woes aside, Jakarta, a low-lying city, has also been sinking slowly.

Social entrepreneur Indradi Soemardjan, founder of one of the city’s few sailing communities called Ayo Berlayar, has already seen signs of the phenomenon: There are days when the dock for his community’s sailboats at Pantai Indah Kapuk gets submerged. Visitors would only see parked boats, with no path to reach them.

Visit the neighbourhood of Muara Baru in North Jakarta, and one can find an inundated mosque sitting in the sea behind a concrete seawall — another grim reminder of the city’s sinking problem.

While climate change has caused sea level around Jakarta to rise by 6mm a year, it is not the main contributor to the problem.

The bigger culprit is unregulated groundwater extraction, which has caused parts of Jakarta — particularly the northern belt — to sink up to 4m since the 1970s, at a rate of up to 25cm a year.

Since only about 30 per cent of the city’s residents get water from the pipe, more than 60 per cent resort to wells that extract water from natural aquifers beneath the city.

This amounts to some 630 million cubic metres of ground water being pumped out annually, causing the land above it to sink.

Experts attributed the water crisis to decades of the local government’s neglect to build reservoirs, pipelines, and water purification plants. Land subsidence meanwhile is putting the city’s available drainage, piping and sewerage systems under great risk of damage.

Mr Indradi, 44, bemoaned that the city government has not invested in another major reservoir project after Situ Gintung, a poorly-maintained 1933 Dutch-built dam that once stood 16m high but collapsed in 2009, resulting in floods killing at least 98 people. Its reservoir used to hold at least two million cubic metres of water.

Although the Jakarta administration had unveiled plans to build multiple reservoirs across the city to create more water absorption sites amid the threat of floods across the city — 40 per cent of which now lies below sea level — progress had been sluggish due to land clearance issues.

At the rate things are going, the city is moving towards a “slow and steady disaster”, said Mr Indradi.

Jakarta’s overexploitation of groundwater has been criticised for years. In 2014, World Bank Group’s water and sanitation specialist Fook Chuan Eng referred to Jakarta as a “swiss cheese”, warning that groundwater extraction is unparalleled for a city of its size.

Research models had predicted that a third of the city could be submerged by 2050.

Still, Mr Jokowi’s solution remains to fast-track a decade-in-the-making giant seawall around Jakarta, puzzling some analysts who said the new seawall could very well crumble and be pulled down with the sinking city.

The electricity infrastructure also has its weaknesses, as the massive blackout that hit Jakarta last month revealed. Power was only restored after dark, nine hours after the outage hit.

The day without electricity was surprisingly pleasant for Ms Yohana Elizabeth Berliana, 23, who got a taste of how the air in Jakarta could be “a lot fresher”.

Air quality is only set to grow worse however, as the blackout had prompted the state electricity firm PLN to commit to building a one-trillion-rupiah 101 megawatt diesel-fired power plant in central Jakarta to provide emergency electricity for the city’s new MRT system. The unexpected blackout on Aug 4 forced passengers to evacuate MRT trains that suddenly came to a halt in tunnels.

Jakarta’s air pollution has already overtaken pollution black spots in China and India on some days. The existing sources of pollutants includes numerous nearby coal-fired power plants, transport emissions, construction and road dust and open waste burning.

A MOVE LONG TIME IN THE MAKING

Against this backdrop, Mr Jokowi’s announcement to move the capital out of Jakarta seems long overdue.

A dig into history shows that Jakarta was never envisioned as Indonesia’s capital when the country gained independence from the Dutch in 1949.

Jakarta, originally a low-lying coastal swamp area, was first developed by the Dutch in 1621.

And while Indonesia’s first president Sukarno took it as the de facto capital post-independence, he had laid the foundation for a new capital at Palangkaraya in Central Kalimantan, which is at the centre of the archipelago and has land aplenty. The area is also relatively sheltered from natural disasters, such as earthquakes and volcanoes common to Java.

But the plan was not implemented, and Jakarta was granted official status as a special capital region in 1966.

Fast forward 50 years, Mr Jokowi rekindled the idea in 2017, determined to move the Indonesian capital out of Java.

Vague plans, including a 10-year plan to transfer all government offices to the new capital city, were first announced in April. Four months later – during which Mr Jokowi visited two locations in Kalimantan – he announced that the new capital will be located between North Penajam Paser and Kutai Kartanegara in East Kalimantan, subject to parliamentary approval.

The move, projected to cost about 466 trillion rupiah (S$46 billion), is a massive undertaking entailing the relocation of 1.5 million civil servants, or a downsized pool of 870,000.

About one-fifth (89.4 trillion rupiah) of the investment will come from the state budget, while the government hopes that rest will be taken up by public-private partnerships.

Money coming from the country’s coffers will be spent on building a state palace, strategic buildings, official residences, open green areas, and a military base.

Economist Enrico Tanuwidjaja, senior vice-president and head of economics and research for UOB Indonesia, said the move to Kalimantan would be added stimulus for the Indonesian economy, estimating its potential to drive up the area’s gross domestic product (GDP) contribution from 8 per cent to 10 to 11 per cent.

Furthermore, Jakarta may gain if “asset swap” were to happen, he said, noting that millennials will stand to gain by tapping on vacated land currently occupied by government buildings if they were to be developed into co-working spaces or start-up incubators.

Using an Indonesian idiom to describe Mr Jokowi’s announcement — literally translated as “with one stroke of the paddle, two and three islands have been passed” — he believes that the capital move would also help to address income disparity in the archipelago of more than 17,000 islands.

Mr Enrico noted that Java accounts for almost 60 per cent of Indonesia’s population and contributes about 58 per cent of its GDP, although its land mass comprises only 7 per cent of the country.

Albeit significantly larger, Kalimantan accounts for only 5.8 per cent of the population and contributes 8.2 per cent of GDP, despite its reasonably well developed airports, roads and widespread access to drinking water, said Mr Enrico who stressed the need for an “equitable distribution of growth” across Indonesia.

CAPITAL SHIFT: BOON OR BANE FOR JAKARTA?

Many residents whom TODAY spoke to doubted that the relocation of the capital would solve its myriad of problems.

They pointed out that even if millions of Indonesians relocate from Jakarta to the new capital, they would be replaced in no time by even more people from other parts of the country, seeking better fortunes in the city.

The city is forecast to add 4.1 million people between 2017 and 2030, according to a Euromonitor report.

The residents added that Jakarta’s problems stem from decades of reluctance on the central government’s part to take bold steps to address, reduce and stop the overgrowth of Jakarta and aggressively promote life in other cities.

Still, there were those who hoped the relocation of the capital would result in a mindset change in the next generation — from the current Java-centric view, which has been deeply embedded since colonial times, to a more Indonesia-centric perspective where more attention can be paid to the other parts of the country which are lagging far behind.

Some noted that the relocation must not end up as an exercise in monument-building and pure jingoism. Behind the fanfare of last month’s announcement should be a resolve that Indonesia would not create another city that sinks under its own weight, even as it solves the problems at hand, they said.

But the country’s poor track record in building sustainable cities does not offer them much room for optimism.

Mr Alvinsyah said: “There had been so many proposals to decentralise. But in the capitalism era, money talks. The big players dictate developments.”

Mr Udayalaksmana added: “Issues (such as transport and housing) are related, but both are not well provided by the government, up to a point where people don’t think of them as issues that the government has to solve.”

His wish for the new capital is that the government will avoid a repeat of the Jakarta problem. “Maintain discipline. Be consistent. Set the capital as the centre of government administration to manage the country well,” he said.

Mr Indradi pointed out that there is not a single city — not even Batam, a relatively new township — that serves as an Indonesian example of a reasonably successful and sustainable development. “There’s not a single city with (widespread access to) drinkable water, a high level of greenery, pedestrianisation,” he said.

Citing his 18-month experience setting up Batam’s waste management system while working for private equity firm Ancora Group, he said that apart from poor enforcement of good regulations, the island was dominated by certain interest groups. “Batam was supposed to be one of the most modern cities in Indonesia, but politics and ‘democracy’ wasted it,” he said.

JAKARTA TO ‘REMAIN CENTRE OF COMMERCE’

In contrast, many in the business community — including Singaporean investors — whom TODAY spoke to are looking forward to the relocation.

One of them is Mr Andy Hidayat, 56, who co-founded meal delivery app Kulina.

Politics-related activities in Jakarta, such as protests, have disrupted his businesses four times a year on average. He is relieved that commerce and politics will soon be separated.

“Politics is supposed to be separated from everyday life. It needs a separate space, so you can do politics more effectively, lobbying, drafting new regulations. The government can be more focused on the policies (in the new capital) than in a very complex city like this,” he said.

Meanwhile, “Jakarta will be like New York”, he said. “It will grow by itself, based on the economy it can create.” Businesses — which have a vested interest in improving the city’s facilities to maximise profits — could be charged a city tax to fund the city’s continued developments after it stops being a capital, he suggested.

Will he consider moving to Kalimantan? Mr Hidayat said his business model requires a critical mass of users in a metropolitan city, while it would take at least 10 years before East Kalimantan gets populated. For now, he would only wait and see.

Meanwhile, some other firms, such as those in logistics construction, property, and education sectors, might see new opportunities developing in the largely untapped land of East Kalimantan.

Education practitioner Afiyah Dimyatie, 67, who started a foundation that runs a kindergarten in Jakarta and a few junior and senior high schools in Cirebon in West Java, said she would explore the possibility of opening a new branch in East Kalimantan “if there’s a good opportunity”.

She foresees a greater demand for educational services in Kalimantan than Jakarta, which is already overcrowded with service providers.

Nevertheless, she will continue to run her business from Jakarta. “Jakarta will not change as a city of trade and industry… Jakarta will always be a historic city for Indonesia with its hustle and bustle,” she added.

Singaporean businessmen who have ventured into Jakarta also see themselves staying put.

Mr Kenny Tan, 52, chief executive of IT logistics and warehousing solutions firm Keyfields who set up an office in Jakarta last year, said there’s still a lot that the city can offer.

In his firm’s first year there, Keyfields closed five deals, doing better than its branch in Yangon, Myanmar, where they only closed six to seven deals in two years. He now aims to double his operations in Jakarta in his second year, aiming to close one deal a month.

“I strongly believe that Indonesia is coming up very soon… In terms of cost, China is not cheap anymore. Vietnam will one day become the second China as well. Indonesia should attract more attention after that,” he said.

Fellow Singaporean, Mr John Tan Wei Min, owns Preshion Engplas, a company manufacturing plastic components for the automotive and electronics industry in West Java’s Purwakarta.

He said that as long as the multinational companies which he supplies to — for exports to overseas markets — remain concentrated in Jakarta, his business will do likewise.

“(The move) will only affect local officials who work in the government office. In fact, it is better for us if some activities or people move out of Jakarta,” said the 63-year-old, alluding to the city’s traffic congestion which affects logistical flow.

Jakarta-based IT systems entrepreneur Tan Yong Han, 39, said that the move would not weaken the allure of Jakarta for him.

Only companies requiring “high touch” with the government, such as Gojek and big developers, might feel an impact, the Singaporean said.

For others, “hopefully it is not too bad” if Indonesia strengthens its e-government capabilities for minor administrative compliance filings and licences for businesses to conduct their operations smoothly, he added.

“Jakarta’s business hub status will not erode in the next 10 to 20 years. Unlike China and India with strong tier-one cities and regional companies outside the capital, all big Indonesian companies are based in Jakarta,” he pointed out.