The Big Read in short: How far have we come in weaning off plastics?

SINGAPORE — Before she leaves home, Ms Cha Yoo Kyung, 27, always makes sure she has three essential items with her: A food container, cutlery and a reusable shopping bag.

By and large, public attitudes towards using less single-use disposables have not changed much, say businesses, environmentalists and consumers.

This audio is AI-generated.

Each week, TODAY’s long-running Big Read series delves into the trends and issues that matter. This week, we look at whether progress has been made in Singapore's push to reduce use of single-use plastics and disposables. This is a shortened version of the full feature, which can be found here.

- To reduce waste and promote sustainability, Singapore has in recent years made a push towards using less single-use disposables, particularly those made from plastic

- These measures, such as a compulsory charge for plastic bags at large supermarkets, have led to positive change in some consumer behaviour

- But by and large, public attitudes towards using less single-use disposables have not changed much, say businesses, environmentalists and consumers

- Convenience and laziness are often cited as barriers to adopting sustainable practices such as bringing reusable containers and bags

- At the same time, consumers and environmental groups are concerned about greenwashing, asking if some businesses are seeking to profit from moves marketed as being green

SINGAPORE — Before she leaves home, Ms Cha Yoo Kyung, 27, always makes sure she has three essential items with her: A food container, cutlery and a reusable shopping bag.

She uses them to pack her lunch every day from coffee shops and hawker centres near her office, as part of a conscious effort to cut down on single-use plastic waste.

“I’ve cultivated this habit for about five years now, and it’s mainly thanks to my mum. She takes active steps to minimise unnecessary use of plastic, and she’s been carrying an eco bag to get groceries for as long as I can remember,” said the Singapore permanent resident, who works as a writer.

Asked if it was difficult to change her behaviour or to maintain it, Ms Cha said no.

“It’s like trying to drink more water throughout the day. You just have to remind yourself and translate that thought into action constantly,” she said.

Ms Cha is part of a growing minority of people here who strive to do more for the environment by reducing the use of single-use disposables and plastics in their everyday lives.

Hawker centres, as ubiquitous as they are here, have also taken baby steps to become greener.

When Bukit Canberra Hawker Centre opened in December 2022, it made the news for its aim to be one of the greenest hawker centres in Singapore.

Among other things, its 44 stalls do not use disposable cutlery for dining in. For takeaways, they use only biodegradable containers or paper bags and boxes, instead of plastic ones.

Still, some diners quickly complained about having to fork out 80 cents for biodegradable containers, underlying the challenge of getting more Singaporeans to embrace sustainability.

That reportedly prompted the operator to then stipulate that stall owners are to charge no more than 30 cents for these containers. This practice is still in place, hawkers there told TODAY this week.

However, this also means that some hawkers have to subsidise the cost of the containers, as they said their actual cost is at least S$0.50 per container.

Similar consumer complaints surfaced earlier this month — over homegrown bakery brand BreadTalk’s implementation of a S$0.10 charge per disposable plastic carrier bag as well as a S$0.50 charge for a woven carrier bag by American footwear store Skechers.

While some consumers support such moves to cut waste, others question if these practices are actually “greenwashing” and aimed at helping retailers increase their profits.

WHY IT MATTERS

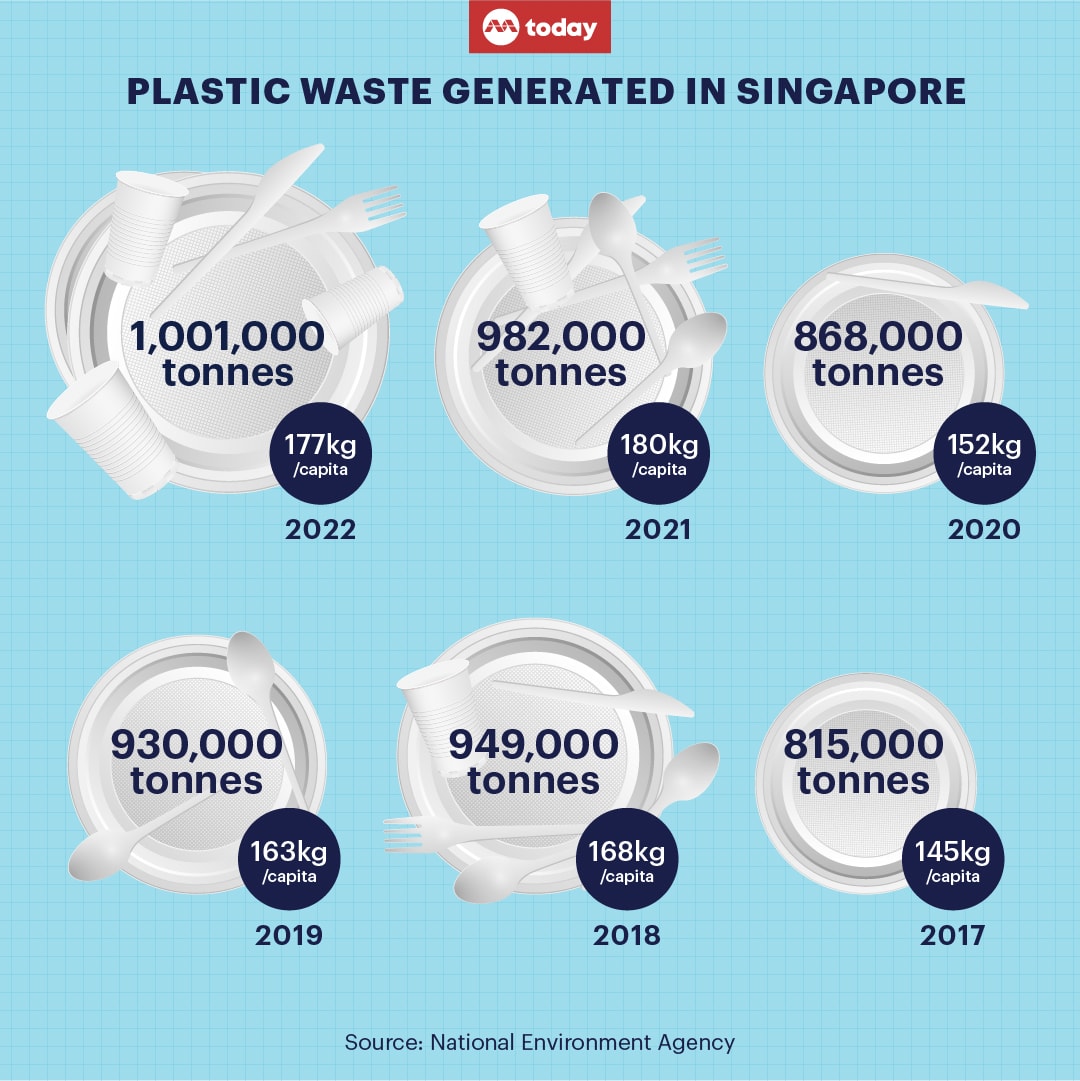

Plastic is the fourth highest type of waste generated in Singapore, with one million tonnes of plastic waste generated in 2022, according to the National Environment Agency (NEA).

This translates to 177kg of plastic waste per capita in 2022, a 17 per cent increase from the 145kg per capita in 2017.

Only 6 per cent of plastic waste is recycled. The remaining 944,000 tonnes, comprising single-use and reusable plastics, are disposed of.

NEA’s website also states that in 2020, about 200,000 tonnes of domestic waste were single-use disposables, comprising both packaging and non-packaging items such as carrier bags, food and beverage containers, as well as tableware and utensils.

It also stated that, based on the current rate of waste generation, Singapore’s only landfill, Semakau Landfill, is projected to be fully filled by 2035, so reducing the use of single-use disposable items will help reduce waste generation.

In recent years, both the authorities and environmental groups have launched various initiatives to nudge people to cut down on single-use plastics and disposables.

These initiatives include:

- The BYO (Bring-Your-Own) Singapore movement started by non-profit organisation Zero Waste SG in 2017, which saw over 430 retail outlets offering incentives to customers who bring their own reusable bags, bottles or containers

- The phasing out of the use of plastic straws by over 270 food and beverage outlets in a 2019 drive by the World Wide Fund for Nature

- The Say YES to Waste Less annual campaign launched in 2019 by NEA in partnership with businesses to encourage consumers to reduce the use of disposables

- A minimum 5-cent charge mandated by the Government for every disposable plastic bag in major supermarkets, starting from July 2023

THE BIG PICTURE

The various moves have moved the needle in changing consumer behaviour in some aspects.

In January this year, Minister for Sustainability and the Environment Grace Fu said the number of plastic bags used at large supermarkets had dropped by 50 to 80 per cent since the mandatory minimum charge of five cents kicked in.

For a retiree who wanted to be known only as Mrs Nathan, the shift towards eco-living started three years ago.

Carrying a reusable bag at a FairPrice supermarket, the 65-year-old told TODAY that her children persuaded her to stop using plastic bags to “save the animals”. She would also bring tiffin carriers when the family eats out in case there is unfinished food.

However, hawkers and other retailers told TODAY they have seen little change in consumer behaviour, as they have not observed any significant increase in customers bringing their own containers.

Those working at several bubble tea stalls, including Chi Cha San Chen, LiHo, and The Alley, said while they welcome customers who bring their own cups, they normally see such individuals fewer than five times a week.

The situation is also similar at food outlets such as Old Chang Kee, Dough Culture, and Jian Bo Shui Kueh, as well as bakeries nestled in public housing blocks.

“Most people in Singapore, both consumers and businesses, are driven by dollars and cents — what is the cheapest and most convenient — and rarely by altruistic reasons,” said Ms Lin Qinghui, founder of social enterprise D2L.sg, a one-stop food surplus and waste manager.

“The culture here is to throw things away. It’s all about convenience, and it’s hard to change this because it’s ingrained in Singaporean society.”

Mr Rayson Lim, 27, who is unemployed, said he did try to pick up the habit of bringing his own container out for four to five months in 2022. Eventually, he stopped because he gave in to his laziness in washing the container after eating each time.

Civil servant Shafiq Ahmad, 29, echoed Mr Lim’s sentiments. “I haven’t tried bringing my own container before, but just the thought of doing the washing after eating makes me feel it’s tiring and troublesome.”

THE BOTTOM LINE

Amidst the push to use less disposable plastic in everyday life, some companies have jumped on the bandwagon through moves such as charging for plastic bags and switching from conventional plastic bags or packaging to those using biodegradable plastic or paper and other non-plastic materials.

However, there has also been debate on whether some of these practices constitute greenwashing.

For example, consumers have taken to forums to talk about how a certain health and beauty retailer has started charging for plastic bags but still uses plenty of plastic for its in-house water products.

Another discussion involved a food court that removed plastic straws but introduced cups with plastic caps for cold drinks, which sell for at least S$2.

A consumer pointed out that cold drinks cost about S$1.40 a cup before the change.

Some questioned whether the amount of plastic used for the cap is less than that of a straw, and whether this is just a gimmick to increase profit.

Others asked if paper or cloth alternatives for disposable plastics used by some retailers are actually more environmentally friendly.

Ms Lin, the environmentalist, cautioned against advocating for non-plastic alternatives without considering Singapore’s “unique” waste management system, where all trash goes to the incinerator.

Hence, she said plastics are efficiently incinerated, potentially reducing their harmful effects compared with countries relying on landfills.

Conversely, some other materials used to replace plastic come at a higher environmental cost as they might not burn as efficiently or as cleanly as plastic.

“Plastic is not environmentally friendly, but if you look at the life cycle analysis across these materials, it’s the lesser evil because the alternatives, like woven cloth, fabric, cardboard, and paper, could actually bring more harm by leaving a larger carbon footprint," said Ms Lin.

A life cycle assessment is a comprehensive method used to evaluate the environmental impacts of a product or service throughout its entire life cycle.

It considers various environmental factors, such as energy consumption, resource depletion, emissions to air, water, and soil, and waste generation at each stage of the product's life.

On NEA's website, in explaining why Singapore does not ban single-use plastics, the agency said that doing so may lead to a switch to disposables made from other materials such as paper or degradable plastics, “which also create waste, have their own set of environmental impacts and are not necessarily better for the environment”.

“In view of the above, instead of advocating a switch to degradable materials, Singapore’s approach is to reduce the use of disposables regardless of material type, and promote the use of reusables.”

Similarly, Mr Yasser Amin, who heads Stridy, a non-profit organisation addressing urban waste management issues worldwide, said terms such as “biodegradable” or “compostable” often confuse the average person.

“It's like a marketing tactic,” said Mr Yasser. He cited how some coffee and cafe chains switched from plastic to compostable straws, when these may not be the more environmentally friendly option.

“Companies should be more aware and capable of conducting life cycle assessments to determine the true environmental impact of their alternatives. People need to question company claims more thoroughly.”

In response to TODAY’s queries on legislation or guidelines to tackle greenwashing, a spokesperson for the Competition and Consumer Commission of Singapore said that it is currently developing a guide to provide greater clarity to businesses on sustainability claims.

It will share more details in due course, the spokesperson added.