The Big Read in short: The gradual demise of mother tongue starts at home

Secondary school Malay language teacher Nur Asyikin Naser reading storybooks in Malay with her children.

This audio is AI-generated.

Each week, TODAY’s long-running Big Read series delves into the trends and issues that matter. This week, we look at the the impact of our mother tongues being less and less spoken at home on the Singaporean identity. This is a shortened version of the full feature, which can be found here.

- More Singaporeans are speaking English at home, as mother tongues fade into the background

- While some parents and students view their mothers tongues simply as an academic requirement, others stress its cultural significance

- Among the attempts to make mother tongue learning more engaging is a new primary school syllabus being progressively rolled out from this year

- Though some young Singaporeans feel indifferent about their mother tongues, experts caution against the dilution of Singapore’s linguistic diversity

SINGAPORE — Mother of three Nur Asyikin Naser uses the limited time she has while driving her children to school to cultivate their love for their mother tongue by playing Malay language audiobooks during the commute.

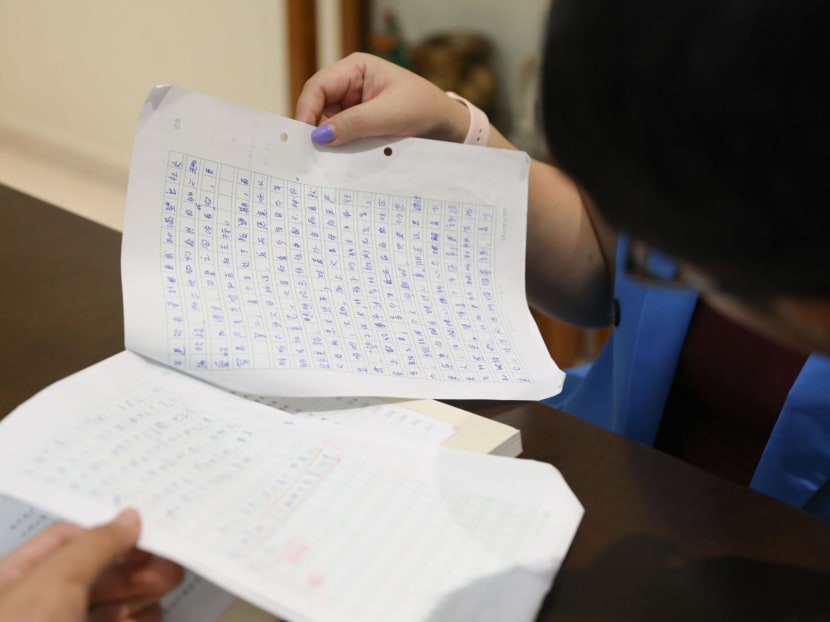

At home, the 35-year-old secondary school Malay language teacher, who has three children aged four to nine, encourages the older children to keep a bilingual journal.

She also recently connected with nearly 100 mothers on a WhatsApp chat group providing Malay language penpals for their children.

“On Facebook, this mummy was lamenting that her daughter’s writing in Malay was very atrocious, so she suggested forming a small group (for their children) to exchange letters. It became quite a big thing, because there was a lot of response,” Ms Asyikin said.

While she has succeeded in fostering a love for their mother tongue in her own children, it remains a work in progress for her other “children” — the students in her Malay language classes, many of whom lack practice outside of class.

As for 35-year-old digital marketer Roystonn Loh, who is a father of three children, aged two to seven, he has seen his children’s eyes “glazing over” when he tries to speak to them in Mandarin. After all, English is the main language at home for the Lohs.

With English having been the main language of instruction in schools here for decades, Mr Roystonn Loh’s children are among the younger generations of Singaporeans who feel less at home with their mother tongues and are more comfortable using English.

As Singapore celebrates National Day on Friday (Aug 9), TODAY takes a closer look at the evolution of this fundamental marker of identity and culture.

WHY IT MATTERS

For Mr Loh and his wife, Mandarin proficiency was not a concern until he realised that there was a gap between his daughter’s current mother tongue ability and the primary school subject requirements.

His concern over his children’s Mandarin proficiency is “purely academic”, as he is comfortable sharing Chinese culture and traditions with his children in English.

But others feel there is more at stake: For them, speaking their mother tongue at home connects their family to their culture and heritage.

There are also practical benefits from mother tongue fluency, such as maintaining connections with older generations.

Ms Asyikin, the Malay language teacher, said many of her teenage students default to using the informal pronoun “aku” to refer to themselves instead of “saya”, which is more respectful when addressing teachers and elders.

“To me, it’s not just about language, it’s also about identity. When you speak the mother tongue, there are certain values, such as respect and politeness, that you learn, as compared to English,” she added.

Though some maintain that culture and language are separable, Dr Goh Hock Huan, an education research scientist at the Centre for Research in Pedagogy and Practice at the National Institute of Education (NIE) said that language transmits “cultural resemblances” through its actual use and script, which another language “cannot fully reflect and transmit”.

While cultural practices and traditions may not be “language-bound”, each language opens up more worldviews, said Associate Professor of Linguistics and Multilingual Studies Tan Ying Ying from the Nanyang Technological University (NTU).

She pointed to Chinese ideas of kinship, reflected in the meticulously categorised terms for familial relationships such as 舅舅 (jiu jiu) for maternal uncle, which provides a “glimpse” into what it might mean to be part of a Chinese family system.

THE BIG PICTURE

With the bilingual scale having tilted heavily towards English in recent times, authorities are working to balance it by making mother tongue learning more engaging and accessible.

Last year, Minister for Education Chan Chun Sing announced a refreshed primary school mother tongue curriculum incorporating games and technology during lessons.

In response to TODAY’s queries, the Ministry of Education (MOE) said schools are progressively implementing the new curriculum, and a news series of printed and online readers have been designed to nurture a love for mother tongue language reading.

The ministry emphasised the important role that parents — as the “first teachers” in a child’s life — play in shaping their children’s attitudes and mindset towards language learning.

“In the early years when children are developing their language skills, it is important for parents to show interest in their child’s mother tongue language and model the willingness to learn with their child, even if they may not be proficient in the language,” said MOE.

Parents and experts also largely agree.

Ms Ksther Lim, 46, used stories to introduce both language and culture to her son, as she read him Chinese tales explaining the Mid-Autumn Festival and Chinese New Year celebrations.

Encouraging her 15-year-old son to be an “effective” Mandarin speaker by focusing on the practical benefits of speaking his mother tongue, rather than insisting on him being perfectly fluent, has helped him stay connected to Mandarin.

Mother tongue educators also emphasised the importance of parent-teacher collaborations in encouraging students to feel connected to their language.

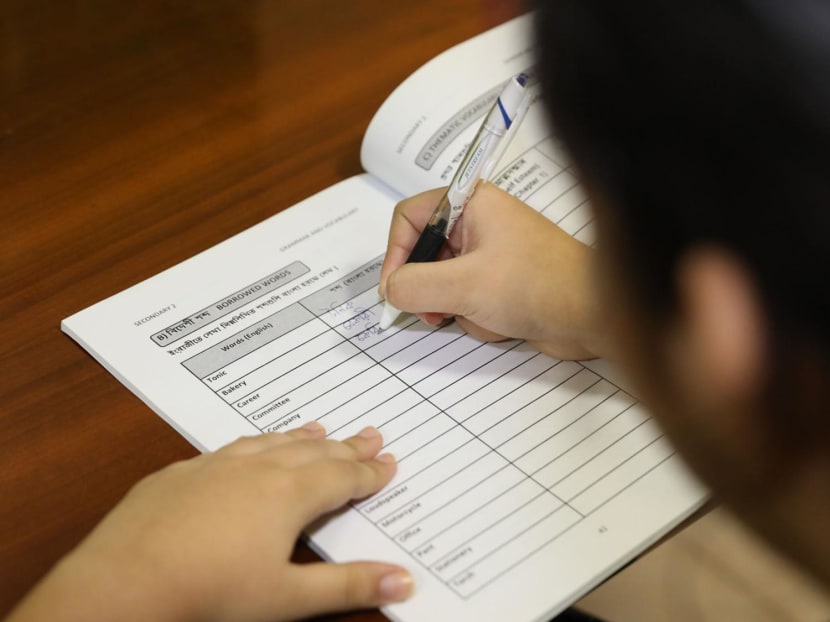

Ms Uma Devi R Jayagumar, the lead Tamil teacher at preschool My First Skool, said students have responded well to efforts to assignments that encourage out-of-classroom interactions with parents.

She regularly prompts children to practise Tamil at home through exercises such as a journaling assignment where students interview their parents on their occupations.

“It takes two hands to clap, because I can have one hour of lessons and then it’s not reinforced at home. Consistency and exposure are needed,” said Ms Uma.

THE BOTTOM LINE

If the home is indeed the most important environment for fostering Singaporeans’ connection to their mother tongues, will the trend towards monolingual, English-speaking households impact the identity of a nation that celebrated its 59th birthday on Aug 9?

Some of those interviewed said that compared with their ethnically-designated mother tongues, the English language serves as a more inclusive medium that unites Singaporeans across different ethnic groups.

For 15-year-old student Aldrin Ardiansyah Fakhrul-Arifin, speaking Malay does not make him more, or less, Singaporean.

Instead, he finds cultural celebrations with family during Hari Raya, and with friends during Chinese New Year, more significant in shaping his identity.

Dr Tan from NTU noted that it is not surprising that today’s youth are more indifferent to any perceived cultural loss from reduced fluency in their mother tongues, or that they have a stronger connection to English.

“I don’t blame kids these days for saying, ‘I’m perfectly okay with English because I’ve got friends from different ethnic backgrounds, and we all speak English together, because there’s also a sense of building national identity (in that),” said Dr Tan.

At the same time, she cautioned, such a mindset is leading Singapore down the “monolingual road” and its linguistic diversity will eventually be lost.

The mother tongue, which as an academic concept is frequently associated with one’s first language, “holds the key” to one’s ethnic identity, said Dr Goh.

“However, this has no conflict with the national identity, as Singapore is a multiracial and multicultural immigrant society. In the past, being able to speak more than one language was a form of local identity and a definite showcase of the kampung spirit.”

Some examples of this kampung spirit would be in saying greetings in the mother tongue of different races and showing respect and acquaintance by speaking some mother tongue languages during different festival occasions of different ethnic communities, he added.

To be fair, there are youths who are keeping this practice alive. Undergraduate student Liow Wanyu, 21, for one, is learning Malay so she can connect better with her Malay friends.

"I started with Malay because its also the national language and most similar to English, through Duolingo and some Youtube videos. Then when I told my Malay friends, they were quite excited and tried to help me learn the language," said Ms Liow.

"That sparked further conversations (with a friend) about her religion, and to some extent she trusted me enough to share about her feelings about the Muslim community in Singapore.

"Maybe she would have told me nonetheless, but I think it helps people feel more comfortable with you, and feel like you are actually trying to get to know them."