The Big Read in short: What has changed in Geylang since dubbed a crime hot spot and 'potential powder keg'?

SINGAPORE — In squeaky-clean Singapore, the district of Geylang has always stuck out like a sore thumb.

Most long-time residents and business owners said that Geylang todayis a scrubbed-up version of its former sleazy self, in large part due to several key law enforcement measures.

This audio is AI-generated.

Each week, TODAY’s long-running Big Read series delves into the trends and issues that matter. This week, we look at the transformation of Geylang since it was described in 2014 by then Police Commissioner Ng Joo Hee as an area with a “hint of lawlessness” and a hot spot for crimes. This is a shortened version of the full feature, which can be found here.

- In 2014, then Police Commissioner Ng Joo Hee described Geylang as an area with a “hint of lawlessness” and a hot spot for crimes

- Residents told TODAY that much has improved in the decade since, thanks to a combination of police crackdowns, government initiatives and the Covid-19 pandemic

- New businesses helmed by young entrepreneurs have also taken a chance by setting up shop in and around the red-light district

- Nonetheless, the “Geylang stigma” still exists in Singaporeans’ public consciousness, with implications for both businesses and residents in the area

- A larger question is what the future holds for Geylang, given its relatively prime location near the city

SINGAPORE — In squeaky-clean Singapore, the district of Geylang has always stuck out like a sore thumb.

Its name alone can evoke imagery of illegal gambling dens, shady drug peddlers and secret society members scattered across its many lorongs (lanes), coexisting alongside the bright neon lights illuminating from brothels.

Geylang’s less-than salubrious reputation is something long-time residents can attest to. Just ask social entrepreneur Cai Yinzhou, 34, who has lived in Geylang all his life.

He recalled having a diverse range of neighbours growing up, from illegal sex workers to those who ran gambling dens directly above his apartment.

Back in the 2000s and 2010s, police raids were a common sight.

From his room, Mr Cai would hear frantic footsteps of fleeing men and women and the sound of boots hitting the concrete — courtesy of the policemen who gave chase.

“Sometimes you’ll see them getting caught. They’ll scream, cry and sob while waiting for police cars to pick them up,” he said.

“That was part of the liveliness of Geylang.”

Today, however, most long-time residents and business owners said that the “problem child” of Singapore is a scrubbed-up version of its former sleazy self, in large part due to several key law enforcement measures.

Bright lights illuminate the previously pitch-dark back alleys. Police closed-circuit televisions (CCTVs) are parked atop street lamps and cover every nook and cranny. Signboards prohibiting the public consumption of liquor past 10.30pm stare you down.

WHY IT MATTERS

Following the Little India riots in 2013, Geylang — the island’s infamous red-light district — was even described by then Police Commissioner Ng Joo Hee in 2014 as a place with a “hint of lawlessness”; a “potential powder keg” of crime waiting to blow up.

Mr Ng had told the Committee of Inquiry into the Little India riots that the police were more worried about Geylang because “all the indicators for potential trouble are there”.

He called Geylang a “hot spot” for crimes such as illegal gambling and drug dealing, and where “unsavoury characters of all persuasion are fond of congregating”.

Most worryingly, there was overt hostility and antagonism towards police presence there, he said, adding that there was nowhere else in Singapore which was “policed more intensely as the 20-odd lorongs on either side of Geylang Road”.

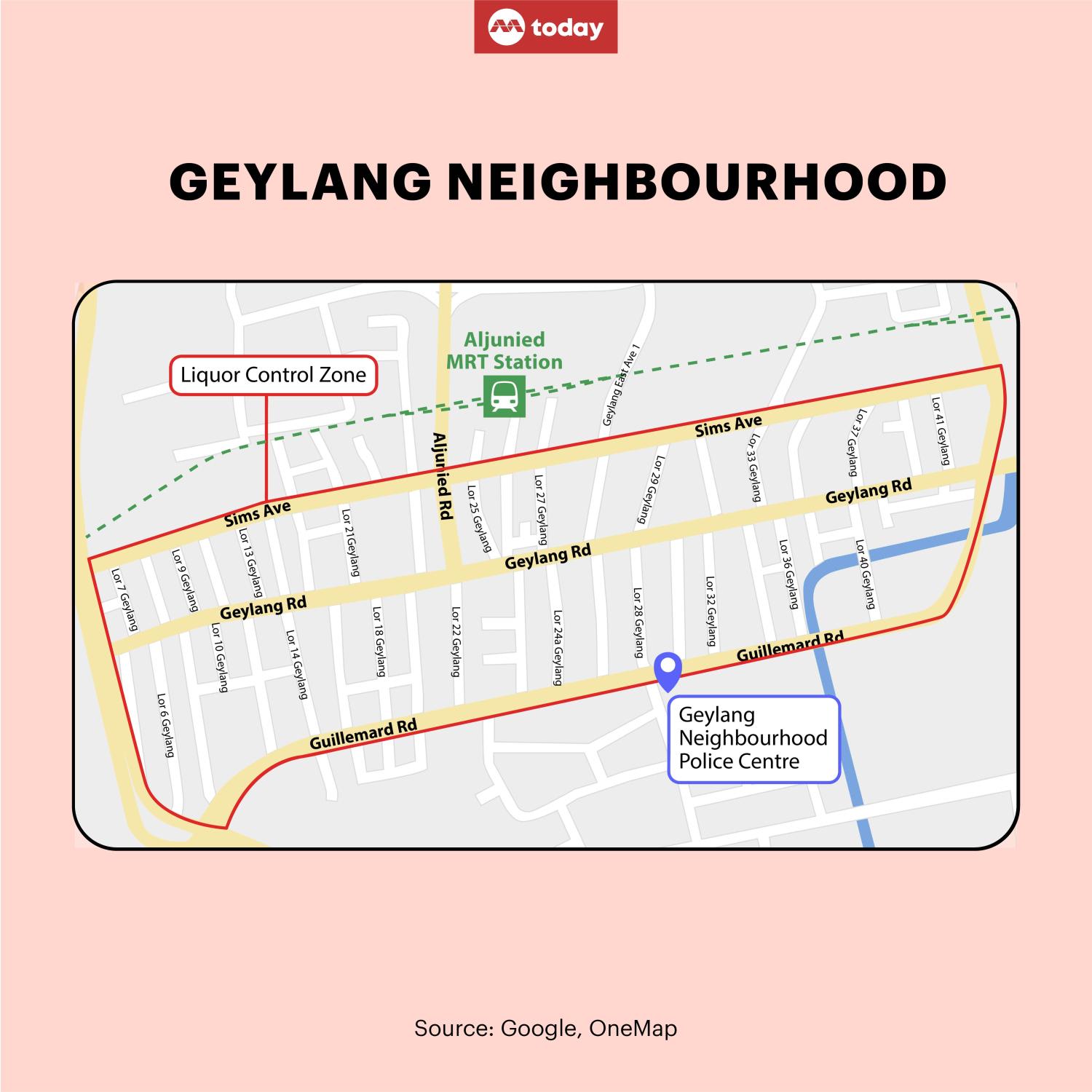

Since then, the police has declared parts of Geylang — a rectangle zone stretching from Lorong 4 to just beyond Lorong 41 bounded by Sims Avenue and Guillemard Road — a Liquor Control Zone.

Liquor Control Zones are defined as areas that carry a significant risk of public disorder associated with the consumption of liquor, so no such drinking is allowed at specific timings.

Residents unanimously agree that the number of illegal “streetwalkers” — prostitutes who roam the streets soliciting for clients — has gone down in recent years.

There are also fewer contraband cigarettes on sale these days, though it is not uncommon to find peddlers selling illegal sex enhancement drugs of various shapes, sizes and colours that may look like harmless candy to the uninitiated.

According to long-time Geylang resident Mr Cai, police surveillance, enforcement and the Covid-19 pandemic — with restrictions on travel and public gatherings — have contributed to the decline in crime in the area.

Dr Wan Rizal Wan Zakariah, who has been the Member of Parliament for the area since July 2020, told TODAY that he has not received any recent complaints from residents pertaining specifically to unlawful activities in Geylang.

“This reflects the significant efforts by agencies to improve safety and security in the area,” said the Jalan Besar Group Representation Constituency MP.

“Geylang has indeed transformed over the years, and it is important to recognise and celebrate these positive changes.”

Despite this, it is hard to completely disassociate Geylang from its historical notoriety.

THE BIG PICTURE

The “Geylang stigma” can be so entrenched that, till today, pawnshop employee Alice Chua does not tell others that she works in the area.

“It raises too many questions,” said Ms Chua, 62, who has worked at a pawnshop at the intersection of Geylang Road and Lorong 22 for over 30 years.

Ms Farhana Ayu, a 41-year-old senior executive in the elevator industry, said that she would have no hesitation going to Geylang by herself for its good food, for instance, but would still be wary of taking her children along with her.

“I’m more concerned about the violence caused by alcohol... and I wouldn't want to answer my kid’s questions like: ‘Why are there ladies standing around there?’,” she said.

Indeed, there was an obvious absence of younger families patronising stalls or strolling along the busy and bustling Geylang Road on TODAY’s multiple visits there both day and night over two recent weeks.

This long-standing impression of a seedy, shady Geylang can cause some problems for businesses there too.

Mr Vincent Low, 40, owner of The Skewer Bar, said he often has difficulties hiring young people to work for him.

“Once parents find out that my bar is in Geylang, they will not let their children work here… This has happened many times,” he said.

For residential units located on even-numbered lorongs, which are commonly associated with vice activities, it can often take up to six months before a willing buyer is found, said property agents familiar with Geylang.

This is because such properties attract only a small pool of buyers — those who view them as investments rather than homes to live in.

These investors often have no trouble renting out units in Geylang to either expatriates who do not mind the neighbourhood’s reputation, or to companies which need to house their migrant workers.

Ms Josephine Teh, a property agent with real estate agency PropNex said: “Not many Singaporeans can accept living in Geylang — even if the apartment is not near the red-light district.”

But property experts added that there is another major, perennial barrier preventing Singaporeans from purchasing properties there: Very few banks are willing to provide loans for Geylang addresses.

This unwillingness stems from a perception that properties in the area are more susceptible to instances of crime and other transgressions, which translates to some risks for the banks.

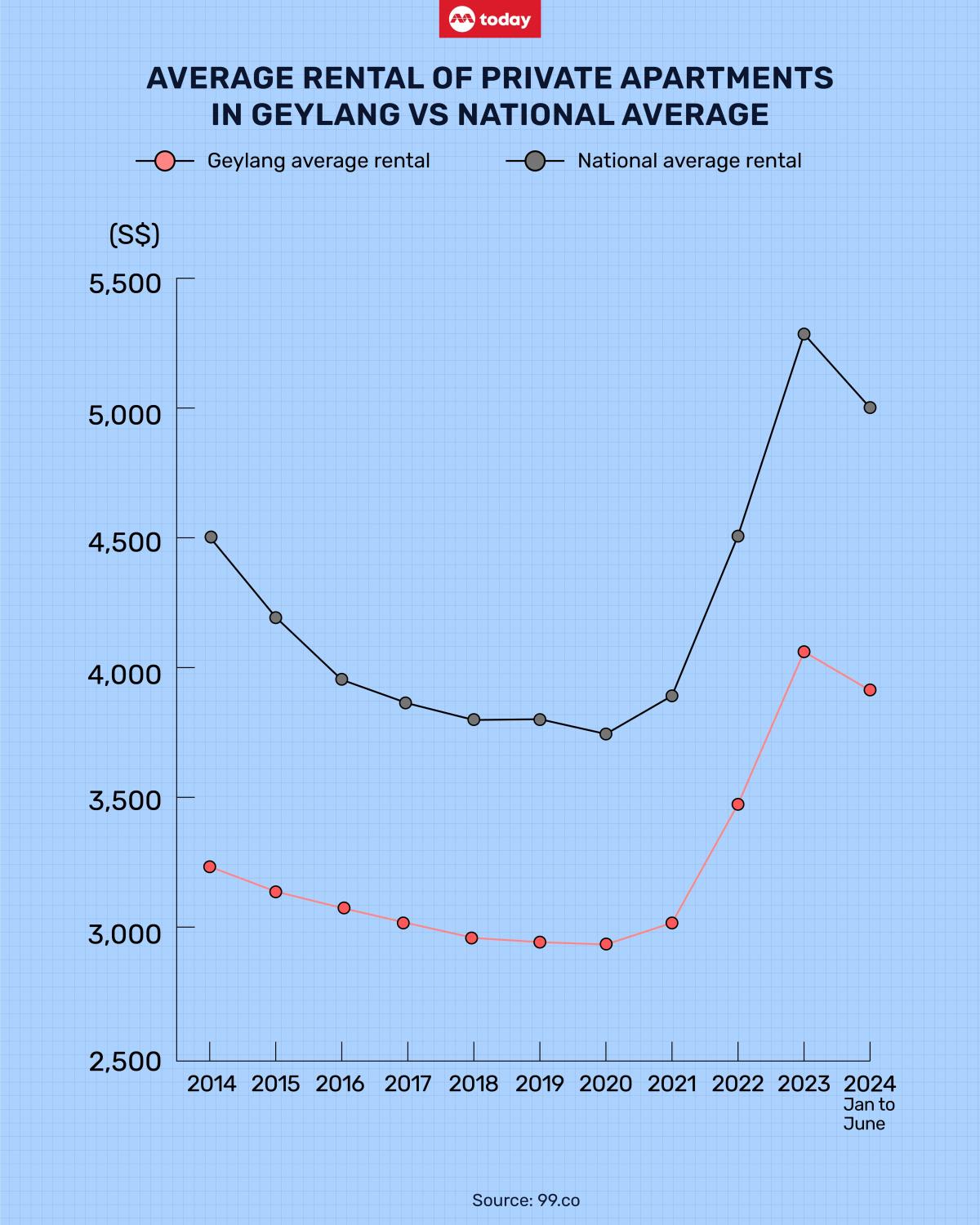

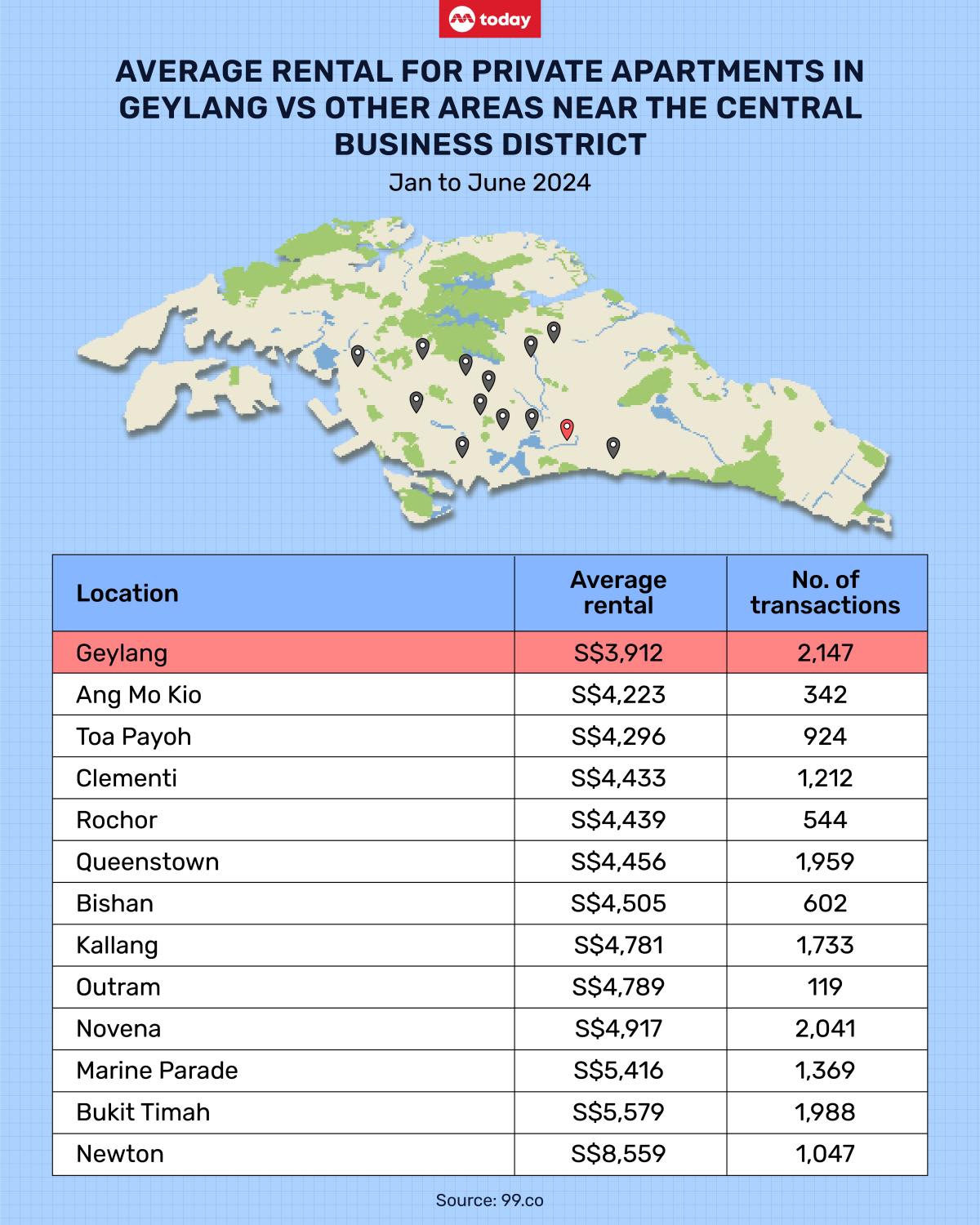

Ironically, Geylang’s seedy reputation does have an upside for those looking to rent an apartment — the area offers “value for money”.

Mr Luqman Hakim, chief data officer at real estate firm 99.co, noted that Geylang’s residents are blessed with a central location well served by transport links, great amenities with various 24-hour eateries, and excellent exercise facilities and sporting events in the nearby Sports Hub — all at relatively cheaper rents.

Indeed, monthly rental rates in private residential units in Geylang over the past 10 years have consistently remained about S$1,000 cheaper than the national average.

THE BOTTOM LINE

For some property developers and analysts, the future of Geylang might look a little like present-day Bugis Village, Keong Saik Road, or Joo Chiat.

The former two were previously well-known red-light districts that have successfully shed their unsavoury past and are now well-known gentrified commercial areas.

As for the latter, a mix of modern boutique cafes have made themselves home alongside conserved shophouses with heritage value — features not too dissimilar from what you would find along Geylang Road.

The fact that crime is no longer as visible and prevalent in Geylang bodes well for its future development too.

For Mr Sebestian Soh, the co-founder and director of real estate investment firm Meir Collective, the shrinking footprint of vices symbolises a blank slate and represents an opportunity to “reimagine” Geylang in a different way.

Meir Collective had bought several commercial properties in Geylang in 2019 before the pandemic struck, and Mr Soh said it has endeavoured to build sites that are flexible and accommodate different kinds of tenants — ones that can celebrate its pre-seedy heritage.

The Government's plans to relocate Paya Lebar Airbase in the 2030s will also enable a rejuvenation of developments — apart from Geylang’s conserved shophouses — given that some developments would no longer be bound by height restrictions.

This could potentially lead to more footfall for Geylang’s businesses, Mr Soh added.

However, some property analysts believe that the gentrification of Geylang will not be a straightforward process, given its large size compared to Bugis Village and Keong Saik Road.

Mr Luqman of 99.co noted that the land parcels in the area are "fragmented with different land owners" and that it would be a challenge to "amalgamate them together to build a meaningful development".

Additionally, property experts said that older residential condominiums that could potentially be put up for an en-bloc sale might hit a stumbling block in the form of owners who have been earning an income by renting out their units each month and see no need to change the status quo.

But even in the face of these possible hurdles, those who have come to adore the place are optimistic that Geylang can continue to evolve from its status as Singapore’s vice hub.

Mr Jeffrey Eng, a long-time resident and embroiderer, has witnessed the transformation of Geylang over the past two decades from his shophouse along Lorong 24A — where he repairs everything from opera costumes to antiques.

He hopes to see Geylang continue to undergo its own repair process too, he said, from “sin city” to a modern, bustling neighbourhood without the red lights — and preferably with its cultural roots intact.

He said passionately: “We should not label (the whole of) Geylang as a red light district, because it is not.”