Migrant worker housing: How Singapore got here

SINGAPORE — The issue of housing foreign construction workers is rooted in a storied history intertwined with Singapore’s economic boom, with the rules changing according to the prevailing sentiments that Singaporeans had towards migrant workers at the time.

Foreign workers in their room at Westlite Papan dormitory on April 21, 2020. The room has three occupants now, down from eight, after workers in essential services were moved out.

SINGAPORE — The issue of housing foreign construction workers is rooted in a storied history intertwined with Singapore’s economic boom, with the rules changing according to the prevailing sentiments that Singaporeans had towards migrant workers at the time.

Initially, during the Republic's post-independence years, the industry’s transient workforce were housed in rented Housing and Development Board (HDB) flats and private homes.

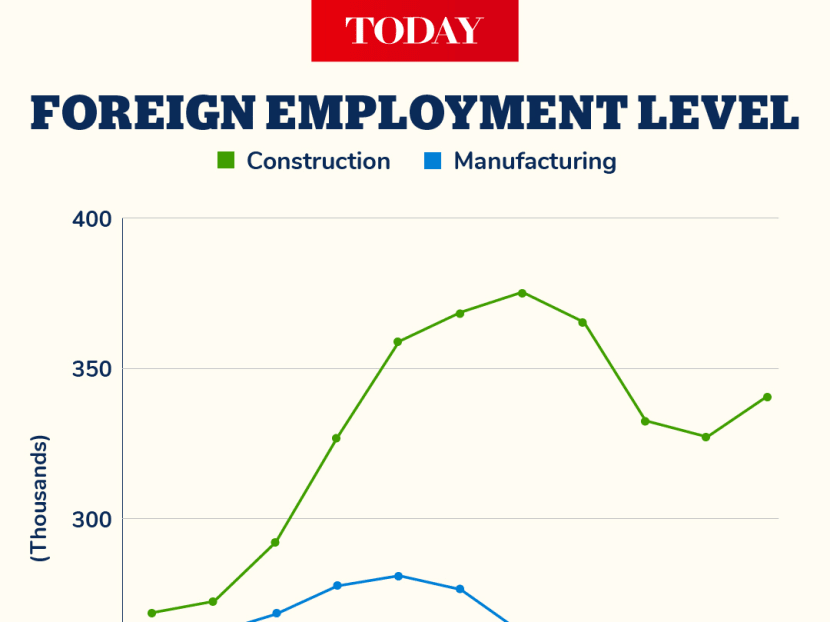

From the 1970s to the early 1990s, migrant workers in the construction industry had come mainly from Thailand and Malaysia.

The turning point came in the 1990s, when more construction workers arrived from Myanmar, India and Bangladesh to support the growing needs of Singapore’s infrastructure expansion.

To support their housing needs, the Government allocated land for companies to build self-contained dorms with recreational amenities for their workers on sites tendered out by the HDB, the Building and Construction Authority (BCA) and the Jurong Town Corporation, now known as JTC Corp.

Said Manpower Minister Josephine Teo in Parliament on Monday (May 4): “One important consideration was ‘what would a migrant worker want at the end of the work day, if he can’t see his family?’ Well, it is to be with his friends, cook a meal he liked, practise his religion. These dormitories were therefore designed for communal living.”

Some factories were also permitted to be converted to dormitory housing, since this would allow the workers to live near where they work.

A number of workers continued to stay in rented HDB flats and private residential premises, subject to certain housing requirements and inspections.

HDB RULE CHANGE IN 2006

In November 2006, the HDB decided to forbid flat owners from subletting their properties to foreign construction workers, unless they were Malaysians, amid complaints from residents.

In its official statements, the authorities had considered the sentiment of HDB dwellers towards their migrant neighbours. As Singaporean households were accustomed to living next to workers from across the Causeway, Malaysian work-permit holders were exempted from this rule.

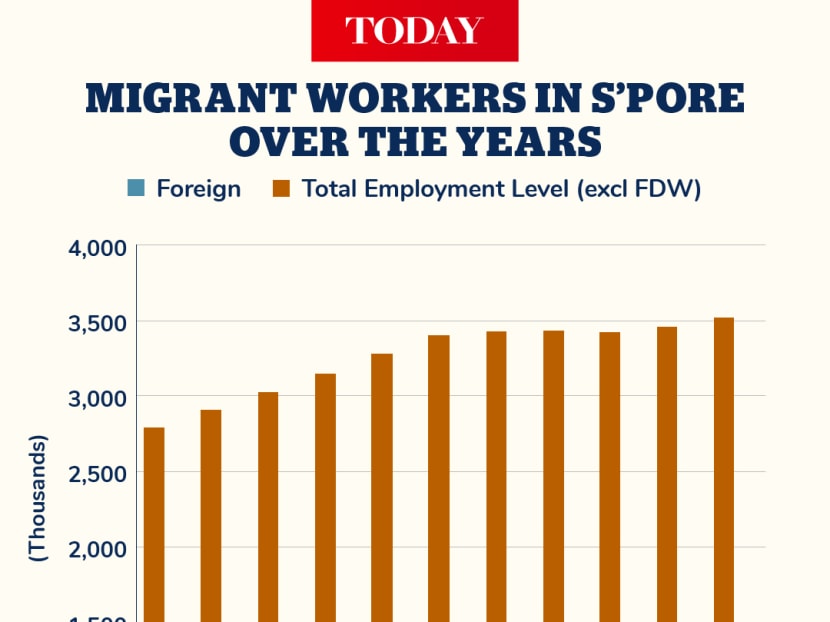

The exemption was also because of a “current shortage of approved off-site housing in the market” at the time — there were 420,000 work-permit holders then, excluding foreign domestic workers, and between 40,000 and 50,000 more were expected in the coming years to build big projects in Singapore such as the integrated resorts.

Ultimately, the plan was to house workers in purpose-built dormitories or workers’ quarters constructed on land approved for off-site housing, such as those tendered out by HDB, BCA and JTC.

But these dorms had not been constructed yet or were in short supply — only around 20 of them existed in 2006, each holding thousands of workers, rather than the tens of thousands in the modern purpose-built dormitories today.

As such, the Government sought to develop new sites into more purpose-built dormitories in various locations, and called for forbearance on the part of Singaporeans if the purpose-built dormitories were to be placed next to housing estates.

The existing dormitories then had largely been located in the periphery of Singapore’s urban landscape, within industrial areas and places not frequented by the rest of the population.

But this spatial marginalisation became less feasible in the light of Singapore’s space crunch and the rising number of migrant labour.

“We will try to put them in places that are not close to housing estates, but it’s not easy to do so. And it’s not possible to place them on an island somewhere, as Singapore is already such a small place,” said then National Development Minister Mah Bow Tan.

“When they come here, you cannot expect them to live in a slum or some corner somewhere. They also need their leisure time and social life, so from time to time we will have to mingle with them, whether it’s in HDB estates, Chinatown, Orchard Road or Little India. They are part and parcel of Singapore.”

2008 SERANGOON GARDENS PETITION

In 2008, some 1,400 out of 7,000 residents in the upper middle-class neighbourhood of Serangoon Gardens petitioned against the proposed housing of foreign workers next to their homes.

The original arguments against the siting were overcrowding, congestion and traffic management, but as the debate progressed, it took on an increasingly classist tone and a rejection of the “alien” presence of foreign workers in the residents’ midst, noted some observers then.

The authorities partially acquiesced to the petition by reducing the size of the dormitory, creating integrated amenities for the workers, and building a separate access road to placate residents.

It also built a leisure hub for residents that was meant to be a buffer between the dormitory and residential homes — Lifestyle Hub@Burghley.

The late Mr Lee Kuan Yew, who was then Minister Mentor, noted in 2009: “When we had to put work permit holders in Serangoon Gardens Estate, there was tremendous unhappiness. But in fact, we‘ve fenced it off, made a different entrance, and I think it will work out.”

Former foreign minister George Yeo, who was the Member of Parliament of the estate within the Aljunied Group Representation Constituency, said then that there were serious considerations on creating townships for foreign workers that were “sustainable and self-contained”.

By the time the 2011 General Election swung around, foreigners comprised 36 per cent of the population of 5.1 million, up from around 20 per cent a decade ago. During a rally, then Workers’ Party (WP) chief Low Thia Khiang told Serangoon Garden voters that he was against the construction of the dormitory in their backyard.

Amid a national swing against the ruling People’s Action Party (PAP) that year, the ruling party lost Aljunied GRC to the WP.

2013 LITTLE INDIA RIOT

When a fatal road accident in Little India in 2013 caused an angry mob mostly made up of foreign workers to attack several police officers, destroy police cars and other emergency vehicles, the riot led to another national conversation on how to accommodate migrant workers in Singapore.

In short, the event led migrant worker housing issues to be perceived primarily through the lens of public order.

Beyond the events leading to the riot, the committee of inquiry into the incident also heard ancillary arguments from residents living in the Little India area on the behaviour of migrant workers when they congregated there.

During the inquiry, Geylang — a known congregation area for migrant workers from China — was also referred to as a “potential powder keg” due to the high crime rates and the hostility towards the police there.

The committee, which concluded its inquiry in 2014, ultimately recommended that dormitories provide amenities, such as remittance and phone card services, which would lessen the need for workers to travel out of their compounds.

Associate Professor Eugene Tan from the Singapore Management University wrote last month: “In the aftermath of the Little India riot in 2013, one line of policy thinking was to provide purpose-built dormitories, with the range of facilities and amenities so that the foreign workers need not venture out and congregate in public places.”

As the dorms were expected to form an increasingly prominent part of the foreign workers’ housing landscape, Parliament passed the Foreign Employee Dormitories Act in January 2015, said Assoc Prof Tan.

THE FOREIGN EMPLOYEE DORMITORIES ACT OF 2015

With the passage of this law that regulates and licenses purpose-built dormitories, Singapore moved towards large, self-contained dorms as the solution to the problem of housing the growing population of migrant workers here.

“The accommodation needs of Work Permit Holders are best met in such dormitories, where there are self-contained living, social and recreational facilities,” then Manpower Minister Tan Chuan-Jin said.

There are now 43 purpose-built dormitories around Singapore, which house some 200,000 migrant workers. Most are from the construction and manufacturing sectors.

Nearly all these premises are located far from the urban centres, and within industrial areas. Several are adjacent to each other, forming large clusters of dormitories.