Capitalism helped create the climate crisis. We should not look to it as the solution

The recent commentary by Bryan Cheang is correct in pointing out that the youthful idealism of the green movement must be mixed with a pragmatic and realistic approach. However, much of what he and other critics construe as pragmatic and realistic can be strongly challenged.

The recent commentary by Bryan Cheang is correct in pointing out that the youthful idealism of the green movement must be mixed with a pragmatic and realistic approach.

However, much of what he and other critics construe as pragmatic and realistic can be strongly challenged. Perhaps the most striking claim is that the best system for addressing climate change is capitalism.

They argue that the most effective way to combat climate change is to harness human creativity by pursuing technological innovation in a free market capitalist system.

This can be questioned on two points. Firstly, should innovation, especially relating to climate solutions, be left to the free market? Secondly, what is capitalism’s track record on climate change?

In terms of innovation, a seminal book by economist Mariana Mazzucato, The Entrepreneurial State, argues that much of the economic success of the United States has come from publicly funded investments in innovation and technology rather than the private sector.

Furthermore, fossil fuels have remained the dominant energy source not simply because of the free market, but because they have received enormous amounts of state subsidies.

Globally, fossil fuels are still subsidised to the tune of about US$5 trillion a year, or US$10 million every minute. A study in the journal Nature found that in the US, tax preferences and other subsidies were needed to push nearly half of new oil production projects into profitability.

Similarly, seven out of 10 Asean countries still provide subsidies to the fossil fuel industry, slowing down the transition to renewables in spite of its increasing efficiency and cost parity.

What these subsidies do is take public money and channel it into the hands of business elites.

With regard to capitalism’s track record on climate change, many reference the environmental Kuznets curve. This states that while growth in the early stages of development leads to environmental damage, further growth will then see a reduction in environmental damage thanks to a combination of technological and efficiency advances.

A key concept that underlies the environmental Kuznets curve is “decoupling”, which states that the correlation between economic growth and emissions can be eliminated, and that we can enjoy growth while reducing our environmental impact.

As these are essentially empirical claims, we can see how valid they are by examining empirical data. Do countries manage to reduce their environmental impact as they reach further levels of growth?

On the surface, there is some evidence that this does play out. A study by the World Resources Institute shows that as of 2010, 49 countries have already peaked their emissions.

Most of these countries come from the developed west, including the US and Canada (both peaked in 2007), France and the United Kingdom (both 1991), and Switzerland (2000).

However, there are major caveats here that are important to emphasise. The most crucial is that for many of these countries, their peaking of emissions came not through technological advances per se, but because they shifted their heaviest industries outside their borders.

In other words, they managed to peak emissions because they exported their emissions elsewhere. Once we account for emissions by factoring in where consumption occurs, the data shows that many of these developed countries have continued to increase their environmental footprint.

If we look at the bigger picture, the evidence is consistent: Even though many countries have peaked their emissions since the 1990s, at a global level emissions have continued to rise, and grew approximately 2 per cent in 2018.

The environmental Kuznets curve is thus negated by what is known as the Jevons paradox, where improvements in efficiency and technology further the consumption of a resource, leading to an increase in emissions.

Furthermore, numerous studies have investigated the extent to which decoupling can be achieved. Yes, some weak decoupling – where the correlation between economic growth and emissions is reduced — is attainable.

Singapore’s emissions intensity target, which is a measure of emissions per dollar of gross domestic product, is trying to do precisely this.

But it has not been shown that absolute decoupling — where the correlation is eliminated — can be achieved. This ultimately boils down to a simple truism: Any consumptive activity involves some use of resources, and resources are finite.

The environmentally destructive nature of capitalism can be boiled down to the imperative to accumulate profit. This is because the profit-seeking capitalist is compelled to maximise production while reducing and externalising its costs, including the environmental costs.

As economic historian Karl Polanyi argues, natural and human resources are thus treated as “fictitious” commodities to be taken as free gifts from nature and depleted without constraint.

The most prominent example of this can be seen in the fossil fuel industry, which has been among the largest and most powerful since the dawn of industrial capitalism.

Because the burning of fossil fuels releases greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, the profits of the entire industry are built on the fact that these costs are not borne by the fossil fuel producer, but by the entire planet.

While carbon pricing policies have attempted to internalise these costs, these policies have generally fallen far below the levels needed to sufficiently reduce the amount of emissions produced.

One reason for this is that, to protect their profits, fossil fuel companies have used their enormous influence to undermine climate policies by actively promoting climate denial through the funding of think-tanks, media organisations and libertarian groups.

The climate crisis, therefore, is not just a simple market failure, but the predictable outcome of a capitalist system.

This brings us to neoliberalism — a doctrine many critics of environmentalism subscribe to. The neoliberal project became prevalent around the 1970s and 1980s, coinciding with the period when scientific evidence was showing that climate change would become a pressing issue.

As neoliberals advocated a limited government whose only objective was to create the conditions for the market to function, any coordinated response by governments to reduce emissions was fervently opposed.

Rather than address climate change, countries have only accelerated it, with fossil fuel use since the 1980s accounting for approximately half of all historical emissions since the 19th century.

Put simply, capitalism is to a significant degree responsible for the climate crisis, and it is not clear that it is even the best system to spur the desired innovation.

It is undoubtedly difficult to envision any alternative to an economic system that has so profoundly shaped our lives. As the saying goes, “it is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism”.

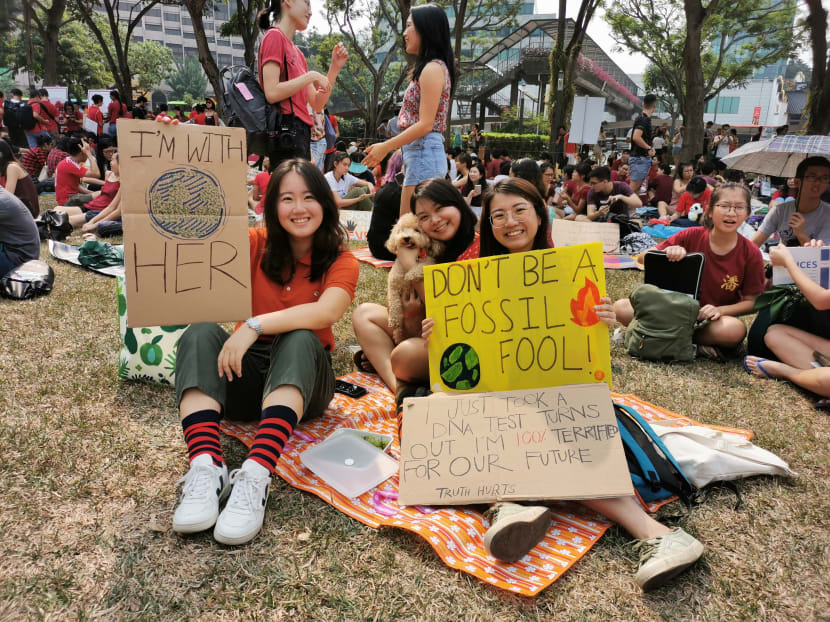

But to think it can be the solution in spite of the evidence presented is to be naively idealistic about the realities of capitalism. It is thus puzzling that the youth climate movement, be it the global movement fronted by Greta Thunberg or the recent SG Climate Rally, has been branded as idealistic.

What these youths call for is the most pragmatic action Singapore, or any other country, can do for the environment — to listen to the science and follow the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s recommendation to halve emissions by 2030 and reach net zero by 2050.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Bertrand Seah is a fresh political science graduate of the National University of Singapore. He was a founding member of a student group that advocates for NUS to fully divest from all fossil fuel assets by 2024. He is currently a member of 350 SG, an environmental advocacy and research group.