Gen Y Speaks: Don't talk to me about grades

As a child, I never liked extended family gatherings. Whether my grades were bad, average or good, the adults always had something to say.

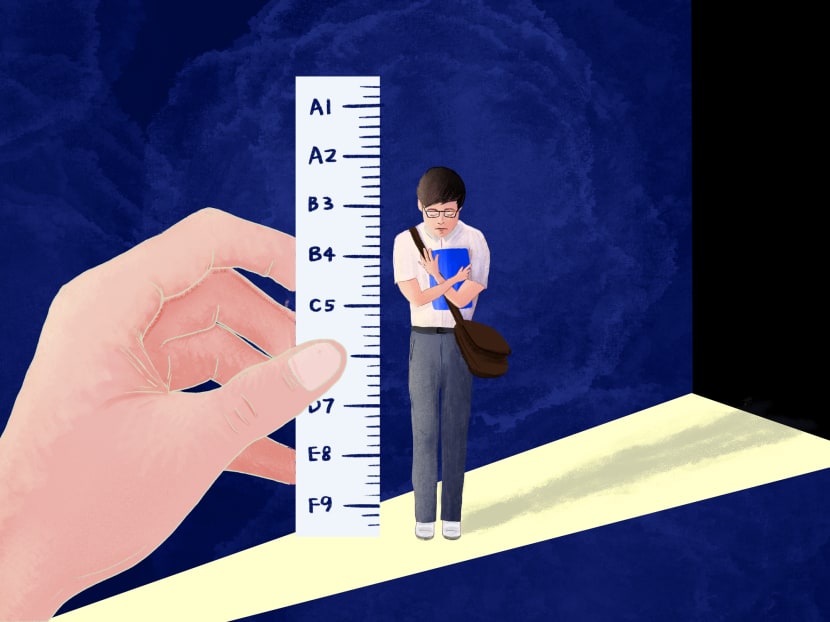

The author said that fearing he would be left behind, he joined in the rush to be a good student at all costs.

As a child, I never liked extended family gatherings, such as during Chinese New Year. Whether my grades were bad, average or good, the adults always had something to say.

In lower primary school, I was hyperactive and could not sit still to do my homework. My grades were horrible. The adults’ conversations revolved around my flaws.

“It won’t do if this goes on,” I recall a relative worriedly telling my mum. I felt like I was a problem, an embarrassment to my mother. After stepping all over my self-esteem, the adults would move on to my cousin.

Remarkably, my hyperactivity disappeared in Primary 4. I was among the three students in my class who made it into EM1, under the now-defunct streaming system of EM1, EM2 and EM3. I did well for my Primary School Leaving Examination and entered Hwa Chong Institution.

I still disliked extended family gatherings. I absolutely dreaded the question from my relatives: “Which school are you in?”

I felt uncomfortable when relatives gaped at me and said: “Oh you must be very smart”, followed by bouts of pretend laughter.

Most importantly, I disliked how it made my cousin feel. He did not do as well. But he was still my bosom friend, and I thought no less of him.

In other words, whether you do well or not, nobody likes to have his self-worth measured by his grades, unless you are among the small minority who enjoy flaunting.

We rarely ask people about how much they earn. Why do the equivalent to students?

I later realised how pervasive and damaging this practice is within Singapore’s wider society.

When I was 15, my friends and I launched a community project at a children’s home. Using games and toys, we wanted to teach English and Maths in a fun way.

The children, aged 10 to 11, happily played the games. But when the English vocabulary and mathematical concepts appeared, they were repelled.

“I dun understand la, everyone says I’m bodoh (stupid),” said a boy pushing a toy car.

Through toy car racing, we wanted to illustrate the concept of speed. But the children viewed any concept resembling schoolwork as anathema.

We often view education as a tool for empowerment. But for the boy I met, education has inadvertently provided society with a “legitimate” reason to reject and exclude him.

He internalised the message that he was a rotten apple, simply because he could not understand his classes.

The boy would not have developed such profound feelings of inferiority if society embraced and accepted him despite his failures in school.

At the children’s home, I was astonished when a girl told me: “I want to go to RGS (Raffles Girls’ School).” In the world of the children around her, RGS did not exist.

My team and I took turns to tutor her for two years. We were there for her when she collected her PSLE results, because her parents could not even be bothered to come.

She made it into RGS. Fists clenched, tears streaming, she was on course to change her destiny in our grades-crazed society.

But she could not fit into the RGS universe. While her classmates joined expensive co-curricular activities such as sailing, fencing and bowling, threw birthday parties and hired private tutors, she needed to work part-time just to survive.

Join our Telegram channel to get TODAY's top stories on mobile:

*TODAY's WhatsApp news service will cease from November 30, 2019.

Her peers compared their exam results subtly but incessantly. She was consistently the last in class and was made fun of. The perpetual comparison of grades made her feel deeply inadequate.

She did not continue her education after leaving RGS. We lost contact after I persuaded her to further her education in some way. Her parting words: “You’re a scholar, you’ll never understand.”

The obsession with grades drives an entire generation of Singaporean minds — who could have flourished in myriad ways — into an arms race to see who can best flourish in exams.

I dislike being reduced to my grades, but that was how reality worked. Most of my junior college's (JC's) coveted opportunities explicitly stated on their application notices: "Only the top 40 per cent of academic performers need apply."

Without good grades, one floated around campus like a second-class citizen. Fearing to be left behind, I joined in the rush to squeeze ourselves into the mould of a good student at all costs, including sacrificing sleep.

To maximise the number of Public Service Commission scholars, my JC identified the best of the best and reserved the lion's share of opportunities for them.

Awards. Book prizes. Overseas trips. Tea sessions with ministers. Invitations by the Navy to experience diving in a submarine, or by the Air Force to watch fighter jets fly.

For every future general, permanent secretary or police commissioner who was glorified on stage, there was someone else who cried at their A-level results and quietly disappeared.

During National Service, I often avoided telling people that I came from a good JC, so that I would not be judged.

I extended the hand of friendship to my compatriots from non-JC streams. Yet I was sometimes told: “You from JC leh. You sure you want to friend us? We very stupid one.”

The practice of judging people based on grades has become so pervasive, that many are doing it to themselves.

I wish to live in an inclusive society which embraces all citizens as equals regardless of their grades. Is somebody with nine distinctions a superior citizen to another person with no distinctions? I do not think so, unless we are not human beings, but distinction-generators.

For the next Chinese New Year, I will not take kindly to any conversation about academic performance.

There is far more to life than just grades. Let's talk about our experiences, hopes and passions instead.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Ashton Ng is pursuing a PhD in Chinese History at the University of Cambridge under a Kuok Family–Lee Kuan Yew scholarship.