Has Covid-19 increased the risk of bioterrorism?

The Covid-19 pandemic has exposed the vulnerability of global societies to biological threats, both natural and manmade, and their potential for disruption.

Since the outset, far-right and Islamist terrorist groups have exploited Covid-19 to aggressively advance their agendas, writes the author.

The Covid-19 pandemic has exposed the vulnerability of global societies to biological threats, both natural and manmade, and their potential for disruption.

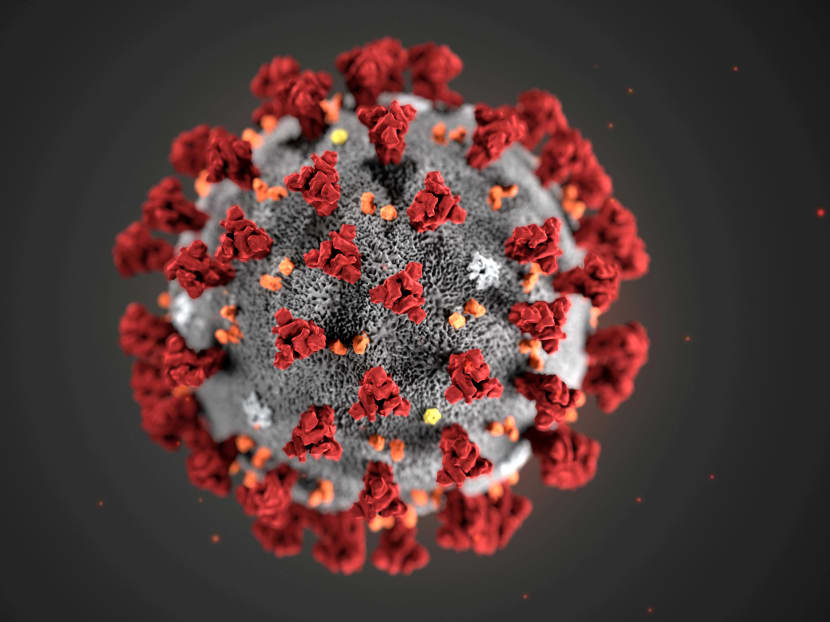

In many parts of the world, the coronavirus has morphed into an invisible enemy, capable of hiding within our ranks and multiplying in secret, before exploding onto the surface.

The crisis has prompted unfounded accusations of biological warfare, with conspiracy theories abounding that the virus originated from a laboratory in Wuhan, and was then deliberately unleashed on the rest of the world by China.

The possibility of terrorist groups of various persuasions attempting or experimenting with bioterrorism, has also been mooted, and the risk of this cannot be dismissed.

The vast human and economic toll from the pandemic highlights the vulnerability of most states to the asymmetric threat from a weaponised virus.

For terrorist groups such as Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (Isis) which seek more effective tools to cause chaos and sow discord, it provides a potential roadmap for their future activities.

WEAPONSING THE CORONAVIRUS

Since the outset, far-right and Islamist terrorist groups have exploited Covid-19 to aggressively advance their agendas.

On social media and other channels, the idea of using the virus as a bioweapon has been widely promoted.

In Southeast Asia Indonesian pro-Isis groups have called on infected followers to spread the virus to their enemies, including law enforcement officials.

Last month, authorities in Tunisia arrested two men over a similar jihadist plot to spread the virus among security forces. One of them, who had to report regularly to a police station, had planned to deliberately cough to infect officers there.

While such attacks or plots have seen limited success, Isis has an apocalyptic worldview, and could be more emboldened in future.

Deemed far-fetched till recently, some experts now say modern advances in biotechnology can theoretically allow a sufficiently motivated violent actor to cheaply acquire and then genetically modify an airborne virus in a lab for maximum contagiousness and virulence.

IS IT FAR-FETCHED?

The feasibility of developing and dispersing a bioweapon varies in difficulty depending on the pathogen involved.

For example, the bacterium that causes the anthrax disease is relatively easy to acquire and can be inhaled through aerosols or ingested via contaminated water supplies.

But an anthrax attack will have a limited impact, both in terms of the geographical area and casualties involved. The illness is not contagious and cannot be transmitted easily from person to person.

While technologies have now become more accessible, and groups like Isis have developed some infrastructural and scientific capabilities, they likely still lack the necessary resources to self-engineer a bioweapon that can wreak widespread devastation.

In a broader sense, movements across the ideological spectrum long interested in gaining chemical, biological, radiological or nuclear weapons continue to be hampered in these efforts by a lack of access, unlike state actors, to adequate technical expertise, materials, funding and infrastructure.

EVOLVING TACTICS

Military doctrines also largely downplay the risk of Covid-19, or a similarly virulent strain, being used as a bioweapon by terrorists on a large scale.

This is because, given its highly infectious characteristics, a virus would not only cripple the attackers, but also risk blowback on their own supporters and communities.

But tactics have evolved, particularly since the turn of the century, from one of targeted attacks to the indiscriminate use of violence, including suicide bomb attacks, wherein collateral deaths among the aggressors are deemed more acceptable.

Among far-right groups in the West, successful bioterror attacks involving transmittable pathogens or toxins have been rare.

Notable incidents include the Rajneesh Cult salmonella poisoning incident, which saw 751 individuals in the American state of Oregon suffer food poisoning when their meals were deliberately contaminated.

Others include the Aum Shinrikyo cult’s nerve gas attack in Tokyo and the Anthrax letter attacks of 2001, where five people in the United States died.

For its part, Isis has used chemical attacks in Syria, and has also showed intent to gain bioterror capabilities.

In 2014, it was revealed that a confiscated laptop belonging to a Tunisian Isis operative allegedly contained information on how to weaponise the Bubonic plague using infected animals.

There was, however, little indication of Isis’ capability to unleash such a bioweapon on humans.

BUTTRESSING DEFENCES

Renewed threat assessments may be needed in an evolving security environment, as terrorists seek to develop new capabilities.

Current deterrence and prevention responses in many countries remain vulnerable to another biological disruption, whether natural or man-made.

Another event on the scale of Covid-19 could more severely dent confidence in governments’ capacity to respond, while also exacerbating fears and distrust far beyond those communities immediately affected.

Health authorities will need to be better prepared not just for the next pandemic, but also against bioterrorism and other public health threats.

The development of rapid detection and surveillance systems that allow for the timely detection and categorisation of a range of potential pathogens is needed in many places.

Intelligence agencies also need to increase cross-border collaborations, and be prepared to more readily share actionable intelligence that could prove crucial to prevent an attack.

Major urban areas could be further fortified through the development and stockpiling of vaccines and medicines that can effectively treat infections triggered by a potential attack. Programmes to adequately train emergency response teams on quick response efforts also need to be implemented widely.

Fears of a major bioterror attack at the hands of a highly motivated and capable violent actor are ever-present.

Such an attack, by nature, is exceedingly hard to detect and respond to.

Enhanced surveillance, a robust public health infrastructure and most crucially, a willingness to heed the advice of front-line experts, are all needed as effective countermeasures.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Amresh Gunasingham is an Associate Editor at the International Centre for Political Violence and Terrorism Research, a constituent unit at the S.Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University.