Helping Singapore's students to learn for life

To help Singapore’s students meet the challenges of an uncertain, fluid future, the school system here must help them embrace the attitude and skill of learning for life, said Education Minister Ong Ye Kung. This is fundamental in ensuring that education remains an uplifting force in society, he added in a speech to educators and officials at the Schools Work Plan Seminar on Monday (Sept 24). Below is an excerpt of his speech, in which he also spoke about the government’s move to reduce the assessment load on students.

With the removal of one mid-year examination in every two-year block, teachers will not need to rush through the syllabus, said Mr Ong, seen here at a press briefing on Friday (Sept 28).

To help Singapore’s students meet the challenges of an uncertain, fluid future, the school system here must help them embrace the attitude and skill of learning for life, said Education Minister Ong Ye Kung. This is fundamental in ensuring that education remains an uplifting force in society, he added in a speech to educators and officials at the Schools Work Plan Seminar on Monday (Sept 24). Below is an excerpt of his speech, in which he also spoke about the government’s move to reduce the assessment load on students.

Today …I will talk about the changes we need to make to ensure education continue to uplift lives and prepare our young for the future.

A recent article in the Economist, published about three weeks ago, lauded the success of Singapore’s education system.

It noted that our system is undergoing a ‘quiet revolution’, and despite our achievements, the Singapore system wants to become better.

That is quite an apt description of the changes taking place.

We do not change for change’s sake. As we change, we are careful to retain the core strengths of our system to deliver students sound values and strong fundamentals in numeracy, literacy, and critical soft skills.

Our good PISA scores are something which we must value and it affirms our approach so far.

In that sense, the changes we push for have never been noisily labelled as something sacred that we have slaughtered.

The system is already well developed and I don’t think we are in the building up phase anymore. However, as it becomes more complex, we need to be clear-eyed that in this matured system, there are trade-offs within the system, and we must take sufficient bold steps to rebalance those trade-offs when needed.

In my speech at the Economic Society of Singapore, I stated four such trade-offs.

First, the balance between rigour and joy – how much robustness we want in the system and hard work we require from students, versus making learning fun and nurturing the joy of learning in our students.

And we know that many of us realise education in schools is at risk of becoming too stressful and maybe some unwinding is in order.

Second, sharpening versus blurring of academic differentiation – how finely differentiated we want examination results to be as a tool for placement and admission, versus blunting the distinction of results between students so that we can gauge learning outcomes without encouraging an overly competitive culture in our schools.

The reform of the PSLE scoring system will be effective in 2021 and I think that is a very decisive step to reduce unnecessary competition.

Third trade-off, customisation versus stigmatisation – how our curriculum caters to students of different learning paces and learning needs, versus inadvertently stigmatising certain groups of students who are less academically inclined.

I know many educators feel strongly about this, and we should then explore how to further leverage Subject-Based Banding to optimise this trade off.

Fourth, skills versus paper qualifications - the importance of attaining credentials such as Nitec certificates, Diplomas or Degrees, versus acquiring skills that make a person effective at the job. Through SkillsFuture, we are bringing both aspects together to establish a multi-path system for our students.

Once we recognise this broader objective of education, examination and grades are comparatively small milestones in the life journey of a child, says Mr Ong. Photo: Facebook / MOE

Underlying the system is a broader definition of meritocracy that our society must embrace over time.

So the next phase of change in education will involve re-balancing these trade-offs effectively, decisively, and many initiatives are already under way.

In 1997, we developed the “Thinking Schools, Learning Nation” vision, to strengthen thinking and inquiry amongst students.

During this earlier phase of change, we reduced curriculum content by about 30 per cent, enhanced teacher training and encouraged the sharing of best practices and ideas across schools.

In 2005, we embarked on the “Teach Less, Learn More” movement as a subsequent phase to further strengthen teachers’ pedagogies.

Our aim was to help teachers better engage students and develop their critical faculties through real-life learning experiences.

Curriculum then was further reduced by 20 per cent, to create time and space for more active and independent learning.

“Thinking Schools, Learning Nation” was framed from a national and systemic perspective; “Teach Less, Learn More”, from the teacher’s perspective.

Both remain relevant and important, but to help our students meet the challenges of an uncertain, fluid future, we must remember they are the ones that will face the future.

We need to usher in a new phase of change – one that is framed based on the students’ perspective.

LEARN FOR LIFE – THE NEXT PHASE

I call this phase of change – ‘Learn for Life’.

‘Learn for Life’ is a value, an attitude and a skill that our students need to possess, and it is fundamental in ensuring that education remains an uplifting force in society.

It is what underpins the SkillsFuture Movement. It also has to be a principal consideration in our school system.

Why has this become so important? In the past, Singapore attracted multinational corporations (MNCs) to set up factories and offices here.

We were the world’s leading producer of disk drives. We knew what kind of talent those MNCs needed, and we teach, we educate and we prepare our students well to fill up those defined job roles.

Today the MNCs are putting their innovation hubs and R&D centres here. Start-ups are sprouting all over, hoping to come up with the next big thing.

We are witnessing the advent of “lights-out manufacturing”, where entire factories are automated. You step into it and you don’t see anything, but in the background, you have personnel with different skillsets to design the system and ensure it hums along.

Today, you can check in and board the aircraft in Changi Airport Terminal Four without interfacing with a single human, and that has totally redefined what a customer officer is supposed to do.

These innovation centres, start-ups and automated environments are creating the jobs of tomorrow.

We have some ideas but not definitive ideas of what these jobs will be; what are these jobs that our students are going to take up.

What we do know, however, is the shape of things to come. We know that our students need to be resilient, adaptable and global in their outlook. They must leave the education system still feeling curious and eager to learn, for the rest of their lives.

These traits are not just adjectives that we tick off, one by one. It is a fundamental shift in our mindset.

I came across a recent article about how the author of the article, who is a middle-aged man, was trying to learn coding.

I thought it explained the concept of lifelong learning quite well.

It is really not about searching for the next course to attend and trying to use up the S$500 SkillsFuture Credit.

Instead, it is about getting used to a state of discomfort. His key takeaway was not the technical coding skills that he picked up, but getting used to the feeling of constantly being inadequate.

So in the article, he described what a coding coach told him: “You need to get used to the idea of being out of depth all the time. You do not solve the same problem twice. You solve one and the next level is even more challenging and once again you feel inadequate. But there is a global coding fraternity that you must learn how to tap on, and then you learn from one another, from that network.”

Once we recognise this broader objective of education, examination and grades are comparatively small milestones in the life journey of a child.

The ability to score in an examination frankly may not matter very much later on in the life of a child.

There are several thrusts under the ‘Learn for Life’ movement, to address the trade-offs I described earlier.

MOE will progressively explain the thrusts and the changes accompanying them.

I will talk about just the first thrust today, which is how to better balance rigour and joy of learning in schools.

A BETTER BALANCE BETWEEN RIGOUR AND JOY

We know that students derive more joy in learning, when they move away from memorisation, rote learning, drilling and taking high stakes exams. Very few students enjoy that.

It is not to say that these are undesirable in learning; quite the contrary, they help form the building blocks for more advanced concepts and learning, and can inculcate discipline and resilience, and get students used to doing difficult and overcome those difficulties.

But there needs to be a balance between rigour and joy, and there is a fairly strong consensus that we have tilted too much to the former.

Our students clearly do well and the outcomes are reflected in our leading PISA scores over the years.

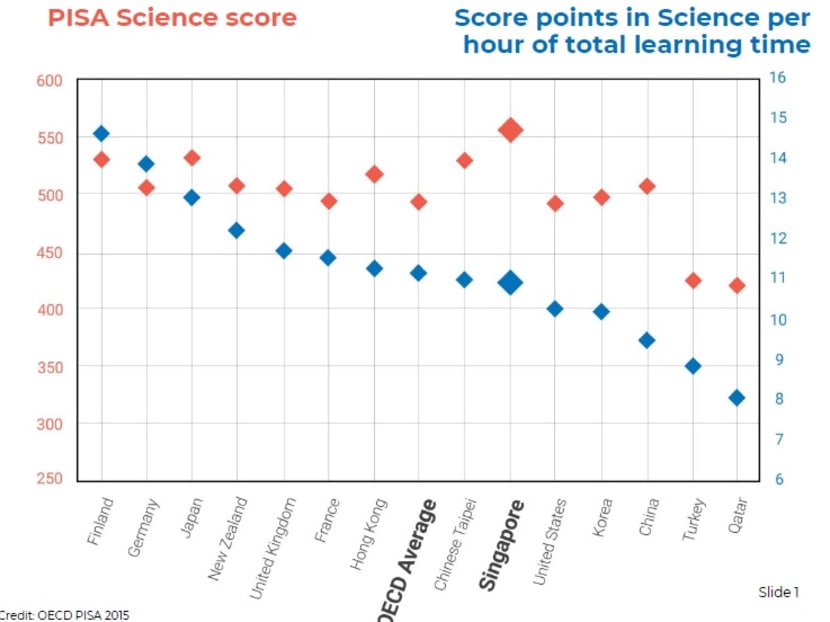

So look at this chart.

The red diamonds show the 2015 PISA scores for Science. Singapore is the biggest red diamond. We scored the highest amongst OECD countries. Well done to all our Principals and educators!

However, if we normalise the scores by hours of study, we get the blue diamonds. So these are scores but divided by hours of study and Singapore is actually below the OECD average if we normalise the scores, behind countries like Finland, Germany, France, UK and Japan.

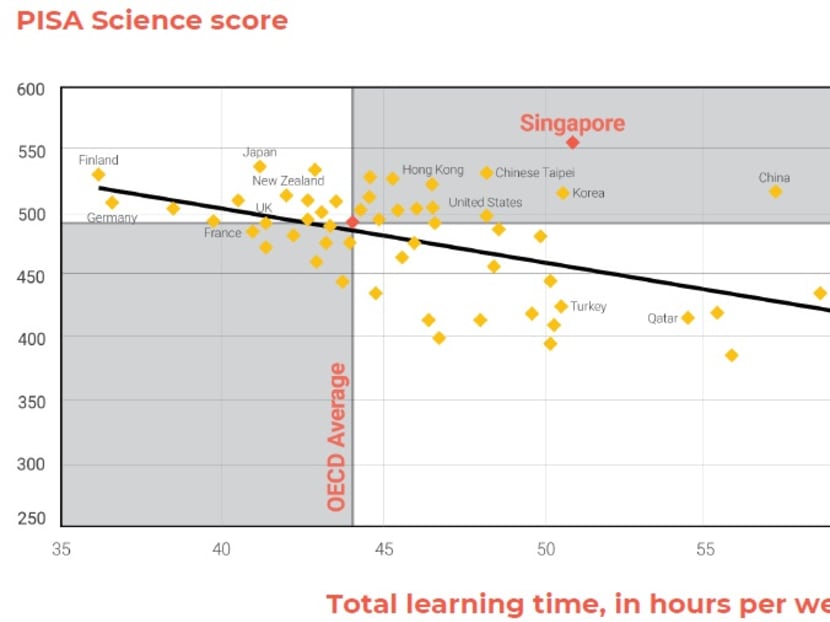

OECD data also shows that there is actually a negative relationship between academic outcomes and the total time spent on learning.

So in this chart (above), the vertical axis is PISA Science score, horizontal axis is total learning hours per week. Strangely enough it’s actually a downward trend. So the more you study, up to about 44 hours. Results are more or less the same, but going beyond that you start to see a drop.

For the country that studies up to 60 hours per week, the results became quite bad. They fell below the average.

Fortunately, if you look at the red dot which is Singapore, we are an outlier – our students study more than their peers in many other countries but we score exceptionally well, which is the Singapore DNA.

I think there is a fairly strong case that we can cut back on unnecessary inflation of effort yet achieve equal or better outcomes.

Our students will benefit when some of their time and energy devoted to drilling and preparing for examinations is instead allocated to preparing them for what matters to their future.

In doing so, we have a few considerations.

First, there is little room for further cut in curriculum. We have already done two significant rounds of reduction, in 1998 and then in 2005, and today our curriculum coverage at all levels are comparable to other education systems around the world.

Further reduction will risk under-teaching. What we should focus on is to curb effort inflation and review our assessment load and tuition load – both of which add to the repetitive and unnecessary effort of studying the same, or even less material, for the sake of scoring well in examinations.

Second, whatever time we may free up for the students, we must avoid the tendency to fill it up with extra practice and drill. Instead, treat this as curriculum time that we return to the schools, return to the principals and teachers, for better teaching and learning.

Finally, we must be careful not to overdo the correction, and inadvertently undermine the rigour in our system.

Japan offers us a very useful experience that we can learn from. In the 1990s, they implemented in their school system an initiative called Yutori. For those who know Japanese, Yutori means ‘relax’.

The objective was to reduce rote learning and memory work, and redirect students to learning creativity and soft skills. But the move backfired – as PISA scores of Japanese students deteriorated, parents’ anxieties went up, and students start to worry that they can’t do well in the university entrance examinations.

Hence the Yutori policy had to be unwound, and five years later, the Government had to increase the curriculum content back and teaching hours back again.

While well-intentioned, Yutori’s objective was ahead of its time, and its implementation, not helped by a rather inappropriate name, was perceived as too drastic a move.

We can learn from Japan’s experience. It is an instructive example, demonstrating the challenge we might face as we re-calibrate the balance between joy and rigour within our system.

REDUCTION OF ASSESSMENT LOAD

Given these considerations, we decided to take the approach of reducing school-based assessment. We have succeeded in doing this before.

As recommended by the Primary Education Review and Implementation (PERI) Committee, MOE removed mid-year examinations and year-end examinations in Primary 1 from 2010. For Primary 2 students, we further removed the mid-year examinations.

As a result, we reduced the stress for lower primary students, who by and large enjoy school more, and have a positive start that focuses on curiosity and growth, instead of examinations and grades.

Teachers also appreciate the extra lesson time to ensure that our young students master the fundamentals.

Today, everyone – teachers, students, parents – have gotten used to not having to worry about examinations in P1 and for most of P2.

Academic results and rigour have not been affected. I think if MOE today, re-introduced examinations into P1 and P2, we may have an uproar!

We will build on this good work. We know that teaching and learning comprises three important components – curricular goals and content, pedagogy and assessment, and together they form a strong triangle.

Today, the three components are not balanced. As we over-emphasised assessment, we inadvertently reduced the time available for schools to focus on teaching and learning.

We need to redress this balance.

We will therefore make another significant move, and reduce school-based assessment load by 25 per cent in each of the two-year blocks in primary and secondary schools.

We will remove all weighted assessments for P1 and P2 students. This means that in addition to what had been removed, we will further remove year-end examinations for P2.

Schools will also not count any assessments towards an overall score for P1 and P2.

In addition, we need to recognise that students go through different stages of learning: from lower to middle to upper primary, and then to lower secondary and eventually, upper secondary. Each stage requires a significant transition and pupils need an adequate runway to adapt to the new demands.

To help students build their confidence and develop an intrinsic motivation to learn during the transition, we should be less hasty in testing and examining students during these critical years. Hence, we will also remove the mid-year examinations at P3, P5, Secondary 1 and Secondary 3.

Schools and parents need not worry about the pace of change being fast. We will implement these changes in stages.

In 2019, we will remove all weighted assessments in P1 and P2, as well as the mid-year examination in S1.

The removal of mid-year examinations at P3, P5 and S3 will be carried out over two years, in 2020 and 2021.

The changes in how students are assessed will free up about three weeks of curriculum time every two years, giving schools and teachers more flexibility to pace out teaching and learning. Photo: Facebook / MOE

I know educators will need some time to digest these changes.

Some educators and parents might be thinking: without mid-year examinations, can we substitute the removed examinations with class tests?

To be clear, class tests are those that count towards year end results. Some have simulated environments like exams, they can be stressful, and they can also lead to loss of curriculum time.

There is nothing wrong with having examinations and class tests, but we need to use them in suitable quantities, balancing the triangle shown earlier. They are part and parcel of teaching and learning. It helps teachers gauge their students’ learning, and even for students to gauge their own learning along the way.

MOE will set guidelines for schools, so that there should be only one class test per subject per term, that can be counted towards the year-end score.

By all means, use formative tools such as worksheets, class work and homework to gauge learning outcomes, and the strengths of each child. These are not high stakes tests or examinations, which result in substantial loss of curriculum time. Our focus is to return the curriculum time to the schools to free up learning and teaching.

BETTER TEACHING AND LEARNING

How will these changes add up? They will free up about three weeks of curriculum time every two years.

This time is now returned to the schools and teachers, and with it, the flexibility to pace out teaching and learning so as to avoid a mad rush to complete the syllabus to prepare for tests and examinations. I am sure all of you know how it was like.

I hope schools will use the time well, for example, to conduct applied and inquiry based learning.

In applied and inquiry based learning, our students observe, investigate, reflect, and create knowledge. And that naturally will take up more time.

For example, we can teach a child the area of a field is length multiplied by breadth. Go memorise the formula and take the tests. It can be done in a short time. But in an inquiry approach, we will ask the child, how do you find out the area of the field and have them discuss and brainstorm.

Some may decide drawing those squares to fill up the field and count them. Others may have their ingenious methods. After that, the teacher may bring them out to the school field to measure the length and breadth of the field, before allowing the students to discover that length x breadth equals area.

In art, we do not just ask students to draw something – when I was in primary school, my teacher asked me to draw a cat or apple and I would just draw.

Now, we show them master pieces, ask them what they observe, and why the artist had expressed himself that way.

We ask them what do you think Monet is thinking of, what do they think Van Gogh is thinking of. We ask them what they want to express, how to express, and from there conjure their artistic creation.

Through the inquiry approach, students think and internalise concepts. The lessons are fun and more applied in nature.

They are more likely to remember and enjoy the lesson, even though that could take up more time. The learning outcomes are better, and these are backed up by research, and also by ancient wisdom.

With the time and space created from reducing the assessment load, we hope teachers will leverage effective inquiry-based pedagogies, to enhance students’ learning experiences.

Our decision to reduce examinations is also backed by the experiences of trailblazers.

One such school is Woodlands Ring Secondary School.

It has removed mid-year examinations for S1 to S3 students since 2012. It has gone beyond what MOE is stipulating today, without affecting their students’ ‘O’ and ‘N’-Level examination performances.

With the time freed up, the school can dive deeper into the curriculum at a pace that suits each learner.

For example, the Mathematics department designed a learning trail for S1 students to extend their learning beyond the classroom. The school has received positive feedback from the teachers, students and parents, that the students are becoming more self-directed and motivated.

I have not touched on junior colleges. It can be a very stressful period for students.

Our engagements with junior colleges tell us that there is a more complex set of issues in JCs, one of which involves preparing students well for the A-Levels in order to enrol into universities. So we will conduct a separate review for junior colleges.

I am confident that the students who are experiencing the changes first hand, will be able to see the value in what we are doing.

However, for this shift to succeed, we will also need to bring in the most important stakeholder – parents – on board.

We will need to show parents that the reduction does not compromise on academic rigour. Instead, we are optimising the number of assessments students have to sit for today for better results.

We must expect some things are beyond MOE’s or the schools’ control – such as parents comparing notes in their WhatsApp groups that often raise anxieties, and sending their children for tuition and enrichment.

I have no intention to heed the calls to ban tuition. Parents do this out of care and concern for their children, and many do-gooders in the community conduct free or low cost tuition to help weaker students cope with their studies, and that’s a good thing.

But there are negative tuition stories too. During my school visits, sometimes I’ll ask them - do you find it stressful in schools?

They will tell me that no, but tuition is stressful. They are very tired on weeknights after school or on weekends, because their day is packed with many tuition classes.

Worst, they find that learning is not fun as a result and lessons have taken over their days and weekends.

So there is room for parents to step back, give children space to explore and play.

On MOE’s end, there is also room for us to step back, review the way we have been involving and engaging parents in school life, and make the nature of partnership between parents and schools clearer.

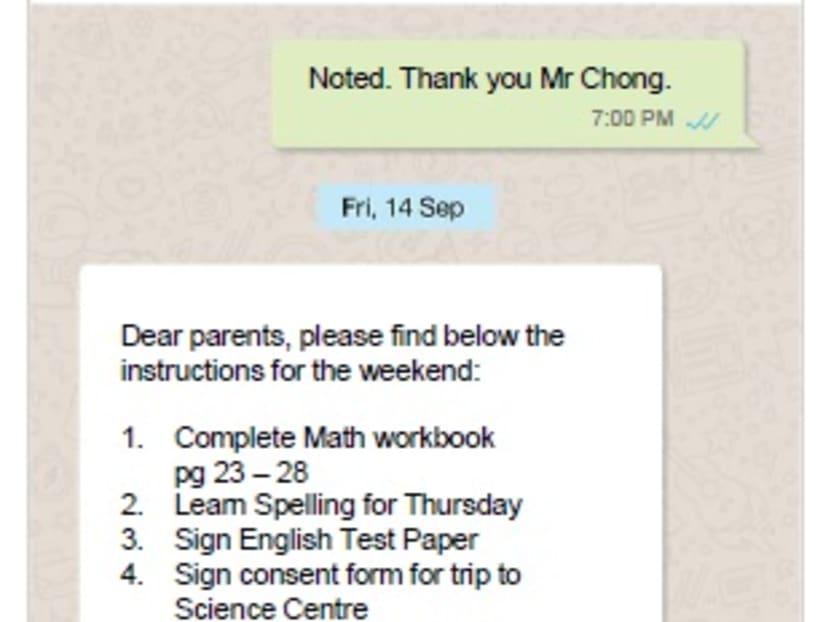

Sometimes, in our zest to engage parents, we may have contributed to their anxieties. For example, some teachers will WhatsApp parents telling them to ensure that their children complete their homework and also list what homework to do.

Take a look at this message.

This is an actual message a parent received one Friday night, asking him to ensure his child completes the given homework over the weekend, while enjoying it.

The teacher meant well, but such messages create expectations for parents to monitor their child’s homework very closely and can cause anxieties amongst parents, especially working parents.

What’s worse, some parents may develop a reliance on these messages, and expect to be reminded on what homework to check. If parents can become reliant, what more the student.

We can be more mindful of how we are shaping children and parents’ behaviour. Teachers can set up a clearer contract with parents at the start of the school year.

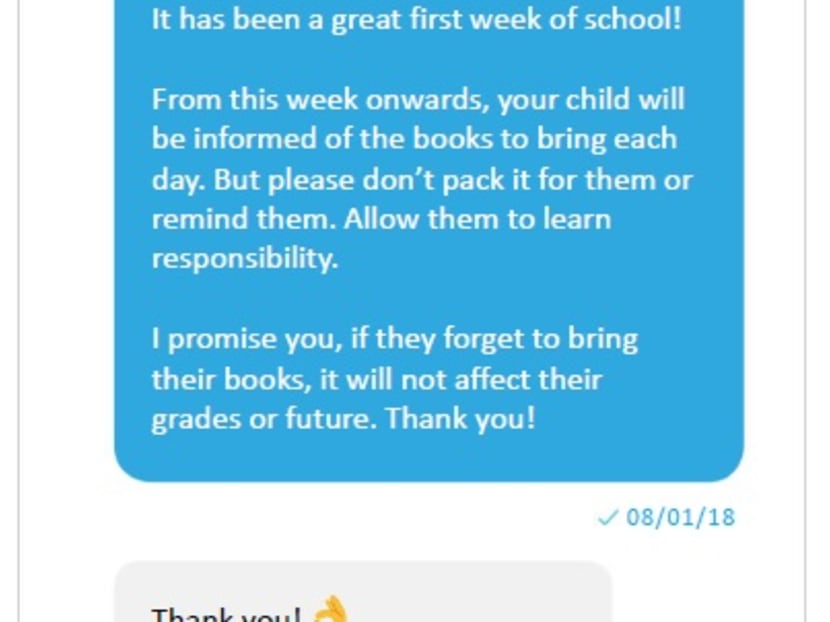

Take a look at this message.

The teacher can for example, assure parents that forgetting to bring a book will not affect a child’s final year exam or future. But if a child doesn’t learn to take personal responsibility, that will certainly affect their future.

So we need to change our language of communication with parents – away from ‘they have to get their work done’; ‘examinations are important and a lot is at stake’; or ‘this is how their results are comparing with their classmates and peers’ to the question that matters most for young students, which is: ‘What makes your child’s eyes light up?’

MOE will develop ways to support our teachers and our parents in this. We will provide guidelines to schools, to give greater clarity on involving and engaging parents in their child’s education, in a balanced and meaningful manner.

We will also support schools in re-calibrating parent-teacher engagement practices.

We will reach out to parents and provide them with effective and useful tips on how to support their child: not just in academics, but in the development of their character and soft skills. These initiatives will be rolled out in the coming year and beyond.

Let me conclude. What I just talked about is a significant but calibrated structural change, to reduce effort inflation and to create a better environment for holistic development. It is part of our journey to constantly evolve and improve.

MOE will support schools and teachers in implementation. But the entire system must move together as one.

Whether it succeeds or not, depends on the intangible professional-cultural changes within schools.

Teachers are at the centre of it, just as you are the central pillar of the education system.

So within schools, it is critical for school leaders to take the lead, be the agents of change, engage teachers and decide how to use the freed up time well to deliver better lessons and better educational outcomes.

With the removal of one mid-year examination in every two-year block, teachers will not need to rush through the syllabus.

This gives them the time and space to explore new areas, and try out more effective pedagogies. If we expect our students to learn through trying and failing and trying again, teachers should also embody this spirit and set a good example of lifelong learning and lead by example.

We have a strong and excellent teaching force, an advantage that not many countries enjoy.

If we harness the passion, creativity and dynamism of our teaching force, we can make bold and meaningful changes to prepare our students well for the future.

This is our collective moral imperative.