Understanding Najib's vocal stance on new govt, 1MDB case

Since losing power in the May 9 general election, former Malaysian prime minister Najib Razak has remained vocal by criticising the Mahathir administration, talking up his record as premier and challenging the 1MDB corruption probe against him. Given his sheer unpopularity, this is somewhat surprising. How, then, should we understand Najib’s post-election political discourse?

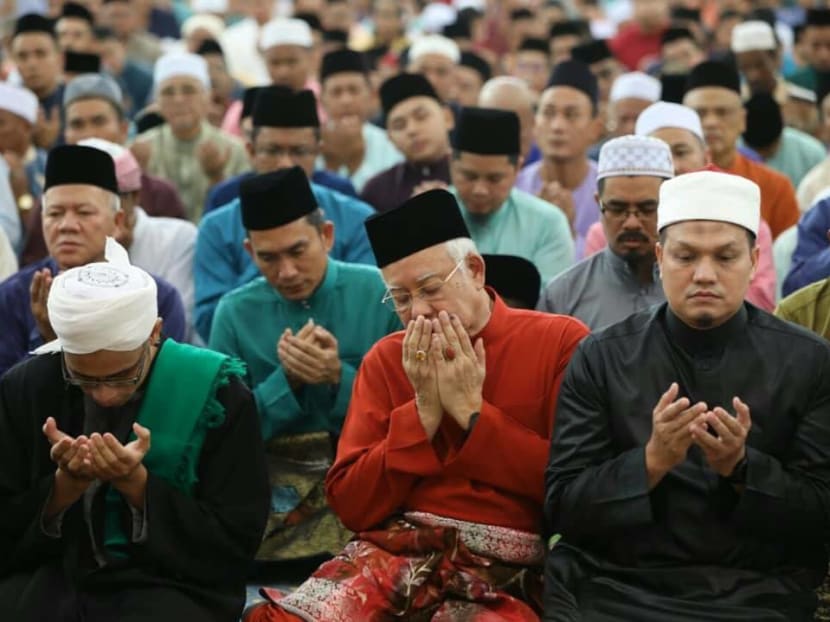

Najib (in red) is making the argument that rather than representing change, the new Pakatan Harapan government is fundamentally hypocritical.

Many quarters have blamed Barisan Nasional’s historic loss in Malaysia’s May 9 general election squarely on its former leader Najib Razak.

His association with allegations of widespread corruption, rampant money politics, and most importantly, policies deemed to have escalated the cost of living, catalysed a substantial drop in the political support for him and BN.

Intriguingly though, Najib has remained vocal by criticising the Mahathir administration, talking up his record as Prime Minister and challenging the 1MDB corruption probe against him.

Given his sheer unpopularity, this is somewhat surprising. How, then, should we understand Najib’s post-election political discourse?

Since news of the scandal that has engulfed 1MDB broke in 2015, public opinion has turned against Najib. And he knows this.

The Pakatan Harapan government has moved quickly to charge him with criminal breach of trust and abuse of power in relation to transfers of funds from a former 1MDB unit to his bank accounts.

In fighting back, he has tried to colour the judiciary under the PH government as incapable of neutrality.

For one, he has repeatedly stated that he “hopes” he will be given a fair trial, while referring to the case against him as a “test” for the court’s independence and transparency.

He has also labelled new Attorney-General Tommy Thomas as prejudicial.

Najib alleges that the AG has disliked him for years and is therefore hunting for “ways” to file charges against him, irrespective of how they may hold up in court.

Najib has painted the head of the Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission in a similar vein.

He also said he was unsurprised to be arrested because this fitted with “the political storyline of the new government” even though he “is innocent” and “not a thief”.

His rhetorical strategy is twofold.

He has painted the judiciary as one that has deemed him guilty before a trial in order to tacitly suggest that the investigations are merely aligning with popular sentiment, but lack legal credibility.

He has also sought to cast doubt over the independence of the judiciary by suggesting it to be a pliant system made malleable to the PH government’s anti-Najib position.

In other words, he is attempting to delegitimise the very possibility of receiving a fair trial.

De-legitimation is also a running theme in Najib’s criticism of the Mahathir administration.

Notably, he has tried to latch on to a dominant belief that many Malaysians who have long supported the Parti Keadilan Rakyat (PKR) and Democratic Action Party (DAP) have of Dr Mahathir Mohamad: that a leopard cannot change its spots.

For instance, Najib has highlighted that in Dr Mahathir’s first tenure as Prime Minister, he used racist labels to demonise the DAP as anti-Malay and anti-Islam.

He also said that Dr Mahathir attacked the previous administration’s 1Malaysia policy because it symbolised a paradigmatic shift from state-endorsed racism to racial inclusivity.

He then dismissed Dr Mahathir’s alliance with the DAP as mere political opportunism. Implicit in Najib’s argument is the suggestion that Dr Mahathir’s racism remains entrenched in his ideological orientation, insofar that it will inevitably colour the PH government’s policy making.

As Najib’s argument goes, rather than representing change, PH is fundamentally hypocritical.

He has reinforced this argument in three ways.

First, Najib has shrouded doubt over that Dr Mahathir’s willingness to hand over the government to Anwar Ibrahim even though this was an election promise foundational to the very formation of PH.

Second, Najib has used Dr Mahathir’s admission that he will be unable to meet many of the objectives outlined in PH’s manifesto within the stated 100-day target, to suggest that PH knowingly and intentionally made false promises to, in effect, steal the election.

Third, he has argued that while PH has long called for widespread reforms, it did not even follow the established protocol when appointing the new Speaker of Parliament, Mohamad Ariff Yusof.

In every instance, Najib’s objective is to chip away at the new government’s claims of transparency, honesty, and thus, credibility.

Given that he has taken a backseat within BN since leading it to its first ever loss, Najib’s rhetorical tactics are not concerned with bolstering his own political future. Instead, his goal is to implicitly link the notion that PH’s credibility is weak to his upcoming trial.

Najib is trying to suggest that if the Mahathir administration cannot even be transparent in its governance despite promising to be so, then how can it – and the various bodies it oversees, like the 1MDB taskforce – be trusted to be transparent in its execution of the investigation and trial against him?

Najib is attempting to construct narratives that make him out to be a political martyr up against the machinery of a vengeful PH government. That much is clear.

What is difficult to make sense of, though, is why he has adopted this approach.

If the election results are anything to go by, his discursive framing is unlikely to resonate significantly enough with Malaysians outside of his own constituency.

One possibility is that he remains surrounded by advisors who have him trapped in a bubble and detached from everyday realities in Malaysia.

Indeed, a former confidante of Najib my colleagues and I interviewed suggested that this was central to BN’s downfall in the election.

It is also possible that Najib is concerned with the political future of his family. His son, Nizar Najib, is the current United Malays National Organisation youth chief for the Pekan division, and may be eyeballing the seat in elections to come.

Or perhaps, Najib is attempting to play up the notion of victimhood so that, when the time comes, he may be able to formally seek political asylum with foreign governments still friendly to him.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Prashant Waikar is a Research Analyst with the Malaysia Programme at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University.